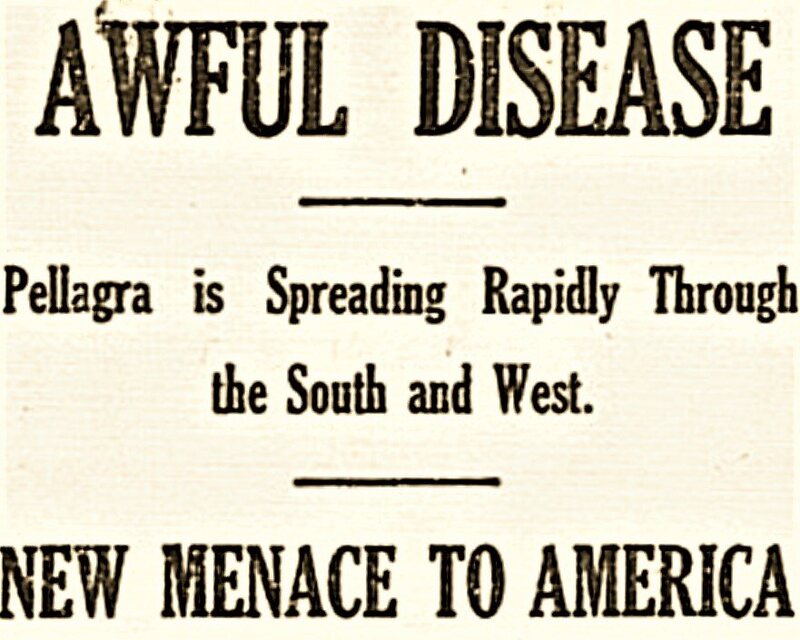

In 1908, the U.S. suffered its first outbreak of a horrendous disease called pellagra. The nation’s first response? Arguing about cornbread recipes.

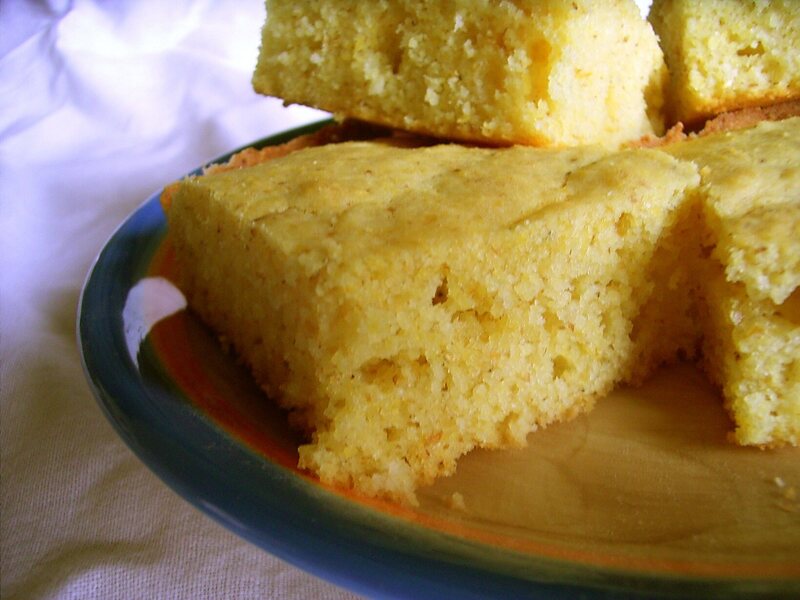

The pellagra outbreak was confined to the South, which happened to be the only region of the country where people ate large quantities of cornmeal. Those two facts were thought to be related, and suspicion fell quickly upon cornbread as a vector of disease.

Southerners grew defensive. Corn itself wasn’t the problem, they said: Pellagra emerged instead from faulty ways of growing corn, or grinding meal, or mixing dough. Most important of all, they said, was who did the baking.

Like so many problems in America, the pellagra epidemic was tangled up with slavery, racism, and poverty. Unlike most of those problems, its solution was thought to lie in fingerprints embedded in the crust of corn bread.

Allow me to explain. According to the USDA, in the first half of the 20th century, families in the North, whether rich or poor, ate just a few ounces of cornmeal per week. By contrast, the poorest farm families in the South consumed as much 12 pounds of cornmeal a week, while the richest consumed 8 or 9 pounds.

How do we account for this? For the most part, the reason was poverty. Incomes in the South were far lower than those in the North: In the richest state, New York, the average worker earned $929 a year. In the poorest, Alabama, he earned $321. To stretch that income, you bought corn. In 1909, 25 cents would buy you 7 pounds of wheat flour—but 10 pounds of cornmeal. Why was the South corn-fed? Because cornmeal was cheap, and most Southerners were very poor. Many subsisted of a diet consisting of little more than cornmeal and molasses.

So let’s refine the question: Why did wealthy Southerners eat cornmeal?

A clue lies in a dreadful, anonymous poem called “The Cornbread Country,” first published in the Baltimore Sun and then widely reprinted across the South:

Oh, for the cornbread country,

The jasmine land I see,

Down there in the dreams of Jackson,

Down there with the friends of Lee.

Indeed, for the past two centuries, the North has recognized the South, and the South has recognized itself, as the land of corn-eaters. I speak not of corn-on-the-cob but of the many items made from ground corn: corn pone, corn pudding, corn dodgers, corn cakes, cracklin’ bread, johnny cakes, hoe cakes, grits, hasty pudding, and spoon bread. Southerners in the U.S. have long embraced corn-eating as a matter of identity. In doing so, they even occasionally weaponized cornbread for use in ideological battle.

The skirmish I’m referring to took place in 1909, just after pellagra was first diagnosed in the U.S.

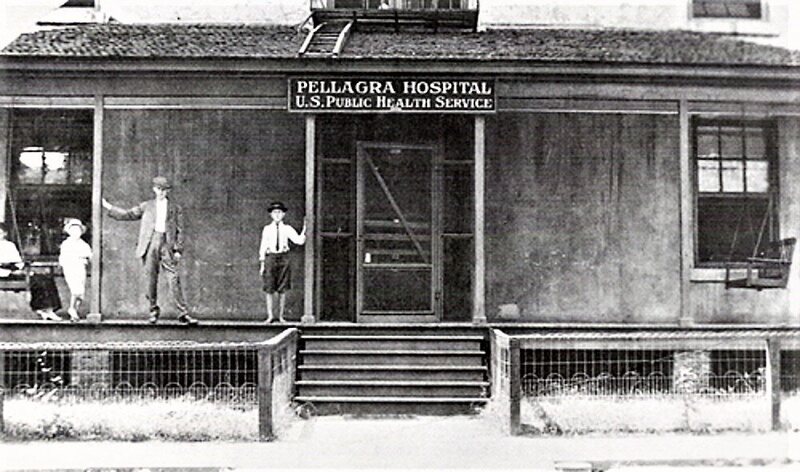

It is a terrible disease: a blistering rash followed by diarrhea, dementia, and death. It had first been identified nearly two centuries earlier—first in Spain, then in Italy—and it was most common in areas where people survived on a diet of corn. In the U.S., pellagra likely killed 100,000 people and sickened 3 million in the early 20th century.

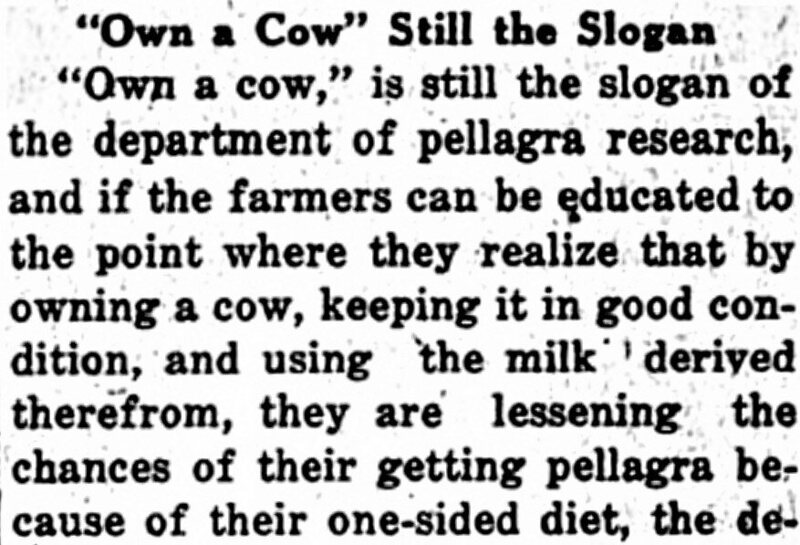

We know now that pellagra is caused by a dietary deficiency of niacin, which is absent from cornmeal but found in fresh meat, milk, eggs, and nuts. But pellagra’s true dietary origins weren’t widely accepted until the late 1920s. When the disease first emerged in the U.S., most doctors believed that it was somehow caused by the cornmeal that was central to the Southern diet. According to one newspaper, “the panic has reached such a stage that … corn pone and corn cake have gone out of fashion.”

Most Southerners, though, weren’t ready to give up their cornbread. They had their own theory about the disease. In Americus, Georgia, a grocer told the Times-Recorder, “Practically every bushel of meal sold here … is ground from Western corn.” By Western he meant what we would call Midwestern—the Corn Belt. Georgians once grew their own corn, but now they planted cotton right up to their doorsteps, and bought cheap imported corn. On its journey from the West to the South, the corn spoiled and became toxic, and those who ate it developed pellagra. So went the theory, at least. As the New York Sun put it at the time, Southerners saw diseased corn as “a sectional conspiracy against the South.”

By 1909, Southerners had absorbed some hard lessons about sectional conflict. Rather than retaliate with force, they looked inward. By buying Midwestern corn, they had despoiled their heritage. How could Southern culture cure itself? By returning to the old ways.

And thus news articles about the horrors of pellagra soon seamlessly transformed themselves into lifestyle pieces about the proper techniques for making cornbread. The MontgomeryAdvertiser in Alabama insisted that badly made cornbread “may produce pellagra or anything else. It is not cornbread.” A writer in the CharlotteDaily Observer agreed. “Corn meal … mixed up with milk, eggs and soda with a spoon and baked in a stove … ought to cause just such ailments as is charged to it. It is a clear case of retribution on the part of the bread.” Proper cornbread contained meal from a local mill, salt, and spring water—nothing more.

And the loaves must be shaped by hand: “The prints of the fingers are left in longitudinal corrugations,” according to the Montgomery Advertiser. “The absence of finger marks is just grounds for suspicion.” The Daily Observer agreed that the cook must carefully shape the pones, “leaving fingerprints on each.”

Those fingerprints served as evidence of who was missing: The cooks of the Old South. The Macon Daily Telegraph explained that real cornbread required “a hickory wood fire, an iron skillet and lid, and an old negro mammy. … She will mix the meal and water, fashion it into pones in her hands, drop the pones into the hot skillet, [and] pat them with her hands.”

The Civil War, by freeing enslaved cooks, had deprived white Southerners of proper bread. And it wasn’t just the cook who was missing—it was an entire social fabric, imagined through a fanciful vision of antebellum racial harmony known as the “Lost Cause”—the belief that Southern ideals had been sanctified by the blood of the fallen, that slavery civilized the enslaved, that God had ordained white supremacy.

In 1909, the same year Southerners panicked about pellagra and cornmeal, the NAACP was founded—a response to, among other crimes, the lynching of more than 900 black men over the previous decade. Racial order in the South was enforced through terror, and justified through storytelling. When newspaper editors celebrated old-fashioned cornbread and lamented the disappearance of enslaved cooks, they buttressed the myths of a happy antebellum South.

Those myths obscured violence—the overt violence of lynching, and the quieter violence of economic exploitation through the sharecropping and tenant farming systems. Poor families spent 40 to 50 percent of their income on food—at least when they had income. Spikes in pellagra tracked the years of economic troubles and crop failures—1909, 1915, 1921, 1930. In 1922, the Charlotte Chronicle noted that tenant farmers had been “compelled to return to … corn bread and molasses for most meals.” The result was yet another pellagra epidemic. As newspaper editors lamented the loss of black cooks, the children and grandchildren of those cooks died of malnutrition.

Eventually, the U.S. halted pellagra. The cure didn’t require the return of black cooks or corn pones decorated with fingerprints. It did, however, involve a new recipe for bread—just not the antebellum-style corn pone editorialists has promoted. The key, instead, was a new ingredient: State and federal laws required that niacin be added to commercial meals and flours, so the pellagra-preventing nutrient was baked into every loaf. (When you buy “enriched” bread today, you are eating a legacy of the pellagra epidemic.)

Through public health laws, the U.S. wiped out pellagra. But we left in place a social system that makes people vulnerable to a new array of nutritional diseases. Eventually, the same quality that made corn an ideal crop for so many generations of Americans—abundant harvests—made it the perfect crop for industrial agriculture, where it yielded raw materials for processed foods. By the late 20th century everyone in America—and many others around the world—started eating a great deal of corn, not as cornbread but as corn-fattened beef and pork, corn oil, and corn syrup. We are all corn-fed now, and the result is an entirely new set of nutritional challenges.

The World Health Organization recently called on nations to tax sugary drinks and subsidize fresh fruits and vegetables. The symptoms of our current malnutrition are not dermatitis and dementia but hypertension and heart disease. The costs—in medical expenses, lost productivity, and human misery—are enormous, and they are borne disproportionately by the poor.

America is a wealthy country, with plenty of food to go around, but the bounty has never been shared. Pellagra, like scurvy or beriberi, is known as a “deficiency” disease—you get it from the lack of a certain dietary nutrient. But the root cause of public health disasters, then and now, is not the lack of certain nutrients. It is a deficiency of justice.

Dr. Joseph Goldberger, the New Yorker who solved the mystery of pellagra in the 1910s and 1920s, once examined an asylum in Milledgeville, Georgia, where pellagra was epidemic among patients—but nonexistent among staff. Doctors earlier had ruled out diet as a cause because staff and patients ate at the same cafeteria. Goldberger noted, though, that the staff ate first. The fresh meat and milk disappeared before the patients dined. It took an outsider to point out that the common meal was not equally distributed.