Picture this short scene in your mind: A sleepy country house sits by the side of the road, birds chirping. Suddenly, a bad guy of some sort—maybe a masked burglar, or a mustached knave—enters stage right and tiptoes through the yard, up to the home's window. He peeks inside, gathering information, and then quickly backpedals, shuffling out of the frame again.

Now visualize the same thing, but try putting a score under it. As the ne'er-do-well sneaks around, what music do you hear in your mind? Does it sound something...like this?

If so, you're certainly not alone. This tune, called the Mysterioso Pizzicato, is a musical go-to for sneaky situations, forever associated with thieves, creeps, stalkers and spies. Along with its villainous name, the Mysterioso Pizzicato has a fittingly roguish backstory—to reach its current level of ubiquity, it has had to muzzle history, defy experts, and slip past hundreds of its more musically interesting peers.

No one is quite sure who wrote the Mysterioso Pizzicato. Some think it was J. Bodewalt Lampe, a ragtime arranger most famous for his takes on dance-craze songs like the "Turkey Trot." Others credit J.S. Zamecnik, a composer who wrote scores for silent films at Cleveland, Ohio's Hippodrome Theater. But most agree that the piece started out life around 1916, as a silent film "mood."

"Moods"—short riffs written to pair with different filmed scenarios—were a way for silent film accompanists to combat a unique type of job drudgery. "Movie theaters were open 10 to 12 hours a day, seven days a week," explains Ben Model, a silent film composer and a resident accompanist at the Museum of Modern Art. "You'd get tired of playing the same pieces."

In the mid-1910s, sheet music publishers, sensing a need, began churning out folios stuffed with variations on musical tropes, for accompanists to pick and choose between. "There would be an agitato"—a hurried, choppy tune, perhaps for an action scene—"and a love theme, and a march," says Model. "And there would be a mysterioso."

Eventually, composers wrote hundreds of these mysteriosos. Although each was a little different, they had certain things in common—they were minor-key, slow, and "just sound[ed] scary," Model says. In a 1912 issue of The Moving Picture News, silent film theater director Ernst Luz describes the mysterioso as "the most beautiful effect of all." "It should be used for such dramatic action, usually quiet, wherein the ensuing action is in doubt," he wrote.

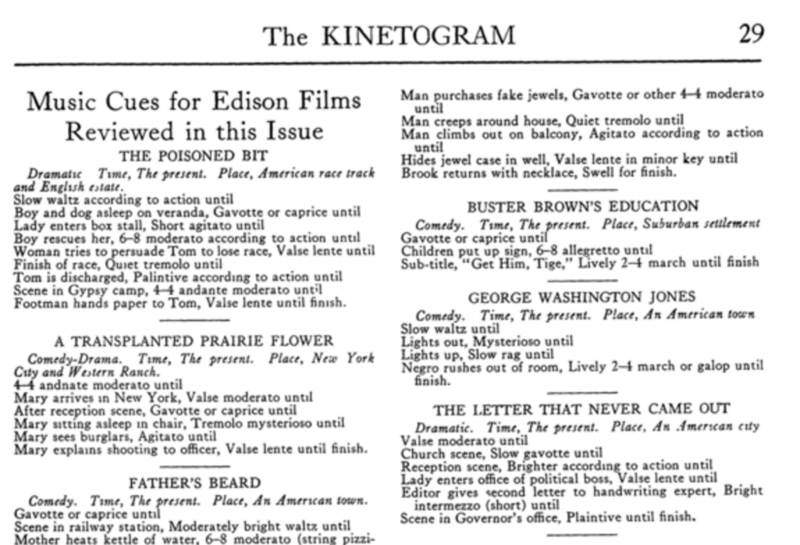

"Cue sheets"—instructions detailing what type of mood should be played during different scenes—give an idea of the mysterioso's specific use. In A Transplanted Prairie Flower, a comedy-drama from 1913, a mysterioso is recommended for the part where Mary, a country transplant new to New York, sleeps in a chair in her city apartment, until she wakes up and sees burglars trying to sneak in. Andy and the Redskins, also from 1913, requires a "mysterioso of Indian character." No matter what the theme of the film, there was always a scene ripe for a mysterioso, says Model.

Strangely, though, very few of these thousands of scenes seemed to require the Mysterioso Pizzicato specifically. Although it was occasionally mentioned in educational articles about film music, players seemed to eschew it. "I've only ever seen it listed once on a cue sheet," says Kendra Leonard, director of the Silent Film Sound and Music Archive. Although Model says people hum the tune at him incessantly, he's never come across it in an actual silent film score. Neither has Rodney Sauer, score compiler and pianist for the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra.

How, then, did it get so popular? The answer likely lies with a different, but related art form—parodies of silent films. When sound came to the movies in the late 1930s, new filmmakers were happy to poke their suddenly outdated predecessors in the ribs. "Warner Bros would make these movies that would make fun of silent films, with corny narration and creepy old music," says Model. (Early cartoons did the same thing—a minute into the clip below, from Van Beuren Studios' Making 'Em Move, a visitor to the cartoon factory walks down a foreboding hallway as the Mysterioso Pizzicato plays.)

There was just one problem: a lot of the tropes these send-ups drew on (people tied to train tracks, caped villains, pie fights) often weren't from silent films at all, but from Victorian-era stage melodramas. Outdated plot points and outdated technology were conflated to form a strange, hybrid genre, which the hip new crowds loved to spoof.

Some of these parodies must have picked up the Mysterioso Pizzicato precisely because it was goofy and over-the-top. Max Steiner, a more serious sound film composer, also began using it somewhat ironically—for instance, in 1944's The Adventures of Mark Twain, it plays under a scene in which the young Twain sneaks up on some frogs.

By now, the Mysterioso Pizzicato has developed a life of its own, showing up everywhere from monster movies to Frank Zappa live performances. Meanwhile, modern-day accompanists largely refuse to embrace it. Model calls the riff "corny and shticky" and hardly, if ever, uses it in his own playing—"many of [the other mysteriosos] are much better," he says. Sauer agrees: "It would be hard to use the piece un-ironically," he writes in an email.

But the Mysterioso Pizzicato doesn't need their help. Somehow, it worms into our ears all by itself—the mark of a true sneak.