American patent clerks in the 1870s could scarcely have imagined how two inventions, filed two years apart, would together change the lonely lives of frontier Americans. In 1874, there was barbed wire, and in 1876, Alexander Graham Bell’s revolutionary telephone. Together, in an amazing display of rural ingenuity, they connected isolated homesteads to their rural neighbors and the rest of the world.

Left to telephone companies and their bottom lines, farm people would not have had telecommunications at all. Building lines was expensive, and hardly worth the effort in sparsely populated areas. But, according to historian Ronald R. Kline, manufacturers underestimated the entrepreneurial, innovative spirit of these men and women. “Ranchers and farm men built many of the early systems as private lines to hook up the neighbors,” writes Kline, “often using the ubiquitous barbed-wire fences that divided much of the land west of the Mississippi.”

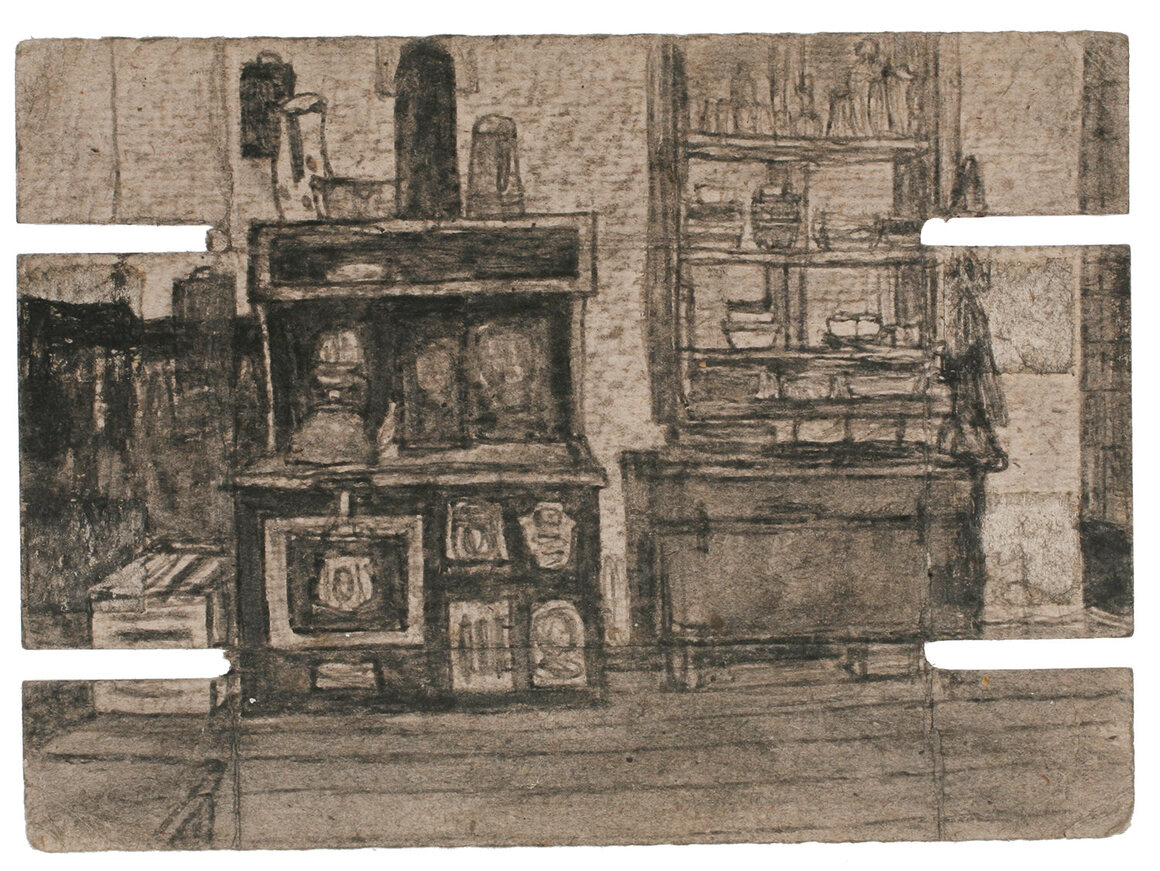

By the 1880s, thousands of miles of barbed wire snaked their way up and down the country. To turn the steel fence wires into telephone lines, they simply had to be connected to a telephone in a house or barn with a piece of smooth wire. The signal then passed through the smooth wire, and along the length of the barbed wire, either to a switchboard or to other houses down the line. In some cases, as many as 20 telephones were wired together—all of which would ring simultaneously with each call, regardless of who was making it and who they were trying to reach. Agreed-upon codes—three short rings for you, two long rings for me—helped people know if the call was for them.

This connectivity fundamentally changed the nature of life on the frontier. In Big Bend Country, Texas, the advantage of the network was not the way it connected farmers to the outside world, but how it linked so-called neighbors who lived miles apart. “Wherever these country telephones have been introduced, and they may appear extremely primitive, they are regarded as an indispensable convenience,” writes Richard F. Steele in An Illustrated History of the Big Bend Country. In the event of a medical emergency, a doctor could be summoned in minutes, without the agonizing wait for a messenger boy on horseback to make it into town and back again.

In Colfax, New Mexico, the barbed wire telephones provided entertainment, too, in a time when ordinary pastimes might have been limited to reading and rereading newspapers and books. “The operator got everyone to listen to the Floyd boys and others playing a banjo, or a piano or a guitar and singing. Five rings also meant that someone with a radio had the evening news on so that all the farmers could get the news and weather report.”

When, elsewhere in the state, two expensive purebred bulls were killed by new trains that ran to Arizona, the railroad company compensated local homesteaders in Hidalgo County by allowing them to use the barbed wire in the railroad right-of-way fence as a telephone line. Emma Marble, a young woman homesteading in the area in 1899, remembered how the line kept loneliness at bay and brought neighbors closer together. “The theory was that we would answer only when our own ring sounded, but whenever the bell rang, every woman on the line rushed to a receiver,” she recalled.

Homesteaders often suffered from what today might be thought of as crippling clinical depression, brought on by days, if not weeks, of solitude, isolation, and physical labor. Marble herself lived alone on a property of 160 acres. “News and gossip were common property, like the sunlight, and we never had any privacies when we went to the telephone.” This bonhomie must have seemed as warming as the sun’s rays, particularly for women, whose role as “angels of the home” often left them stuck in cabins or sod houses. That said, the number of people on the line at any given moment could be irritating. Every now and then, someone cut into a conversation, while multiple listeners reduced what any one of them would be able to hear.“Get off the line!” was a familiar refrain.

The barbed wire telephone also helped homesteaders escape the scrutiny of the government land inspector, who made frequent trips through Hidalgo to make sure homesteaders were obeying the letter of the law. “There was only one road to travel,” remembered Marble. As the inspector reached Lordsburg, friends quickly flashed the news over the barbed wire telephone to update one another on his progress as he went. “He always found the women working at some household task and all surprised as all-get-out to see him!”

The line was far from perfect, of course. Early telephone wires were shoddy, even when they used the “correct” copper wire. Barbed wire was particularly thick and heavy, and grew weightier when it rained. Even with closely spaced posts, the wire had a tendency to snap. Outside intervention, both nefarious and otherwise, was also a risk. The American Telephone Journal, in 1908, described how a prosperous farmer’s private line gave him “little to no trouble … except when mischievous boys ground the line by the aid of baling wire.” The Hidalgo County homesteaders’ line worked only in dry weather, and “hummed a great deal when the green mesquite would grow and touch the wire.”

Writing in Telephony magazine in 1886, J.L.W. Zietlow described the resulting chaos when cattle broke down the fence wire, cutting off people who had come to rely on their telephone. “It goes without saying that I have been prejudiced against fence wire telephone lines ever since,” Zietlow wrote. “I know of many bad mishaps; and in one particular case, the loss of a human life is attributed to a barbed wire telephone line failing to work.” It seems far more likely that barbed wire telephone lines saved lives, especially in cases of high-risk pregnancies or falls from horses.

Until the phone companies eventually wired the rest of rural America decades later, these inconveniences were minor—someone had to go out and ride the fence anyway—for a connection to the outside world, one that shrank the open frontier to a much, much more manageable size.