![article-image]()

The old walls of Pentridge Prison, Melbourne (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The history of Australia is closely interwoven with its role as a British Empire prison colony, and in many ways this ostensibly grim narrative could be said to have helped define the culture and developing personality of the nation over time: the sense of camaraderie and “mateship," the celebration of anti-establishment underdog heroes, even the bawdy language of Australian humor are able to find their correlates within the culture and mentality of a prison population.

Now 240 years after the first convict ships arrived, Australia has exploded into one of the key players on the world stage — with a robust GDP and a wealth of cultural exports. But if the mentality of a former prison colony has been assimilated over the years into a contemporary Australian culture, what of the physical scars left by that penal past?

In this article, we’ll be taking a look at seven former prison sites spread across Australia and Tasmania, some of them abandoned, some long since disappeared, but others earning a roaring trade as museums and sites of "dark tourism."

![article-image]()

A collection of death masks at Old Melbourne Gaol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The Prison Colony

During the late 18th and 19th centuries, Australia saw a radical population shift in the form of Western colonization. But it wasn’t just explorers, opportunists, and those in search of a fresh start who made their way to the Australasian continent; in the space of 80 years, the British government would send more than 165,000 convicts to Australia by sea, to be confined in any of a series of growing penal colonies on the island.

The Industrial Revolution in Britain resulted in a huge displacement of the population, and a loss of many jobs. As a result, the work houses were full, petty crime was at an all-time high, and the nation's gaols were overcrowded to the point of crisis. The people were hungry, and eight out of ten prisoners were in on theft charges. Up until 1776, somewhere in the region of 60,000 prisoners were deported to America, but after the Revolutionary War and the founding of the United States another solution had to be found to the growing incarceration rate.

Transportation was deemed more savory than execution, and so when James Cook claimed the Australian east coast in the name of King George, a decision was made to start shipping the excess prison population away to this distant colony.

The first convict ships arrived in Botany Bay, the soon-to-be site of Sydney, in 1788. By 1824, penal colonies were established to the north in present-day Queensland, including a settlement at Moreton Bay that would in time grow to become Brisbane. The Brisbane penal colony was closed in 1839, from which point people would begin to colonize the area freely.

![article-image]()

Fremantle Prison Inmates, 1971 (photograph by Iwelam/Wikimedia)

Western Australia

In the west of Australia, transportation of convicts was at its peak between 1850 and 1868, during which time almost 10,000 detainees would be incarcerated in purpose-built prisons. The most famous of these facilities was Fremantle Prison, a 15-acre site constructed using convict labor between 1851 and 1859.

Fremantle Prison remained in operation for almost 140 years, but it never truly recovered from a violent riot in 1988 in which guards were taken hostage and fires caused approximately $1.8 million in damages.

Today Fremantle Prison is the only World Heritage Listed Building anywhere in Western Australia. Since being memorialized in the form of a museum it has received more than three million visitors, offering tours of both the prison itself as well as the extensive labyrinth of tunnels located beneath.

![article-image]()

Fremantle Prison Main Cellblock (photograph by Ghostieguide/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

Fremantle Prison Three-Division (photograph by Ghostieguide/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

The Fremantle scaffold, last used in 1964 (photograph by Chris Quinn/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

Fremantle Prison Tunnels (photograph by Ghostieguide/Wikimedia)

Victoria

In the state of Victoria, then still part of New South Wales, the first convict ships arrived in 1803. After several tentative attempts at establishing a penal settlement, the Port Philip District was sanctioned in 1837. Over the next 12 years, approximately 1,750 convicts were shipped directly from England.

The Old Melbourne Gaol, one of Australia’s most notorious penitentiaries, was opened in 1842. It served as the city's main prison until 1929, during which time a total of 133 inmates were hanged on-site. The prison boasted a number of "celebrity" inmates, including the outlaw bushranger and national underdog hero Ned Kelly, as well as the serial killer Frederick Bailey Deeming. Deeming, recently arrived from England, was theorized by some newspapers to be the true perpetrator of the Ripper murders in London. Both men met their end at the Melbourne scaffold.

Today dark tourism to Old Melbourne Gaol is a thriving industry, with the site receiving an estimated 140,000 visitors each year. The main cellblock has been turned into a museum, each individual cell adorned with personal effects of its former occupants, newspaper clippings, and rows of death masks in glass cabinets.

![article-image]()

The main cell block at Old Melbourne Gaol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Old Melbourne Gaol exterior (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Cells in the Old City Watch House, Melbourne (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

A holding pen in the City Watch House (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Convict paraphernelia at Old Melbourne Gaol (photograph by Darmon Richter)

The corpses of prisoners executed at Old Melbourne Gaol were largely buried onsite in mass graves, and these would later be disturbed by construction work in 1929. When the graves were unearthed, there was a frantic rush of looters looking for a grisly souvenir, and before the police were able to take charge of the situation many of the bones had been removed.

The bodies left were reburied at Pentridge Prison.

Pentridge Prison opened in 1851, just north of Melbourne at Coburg. It operated through 1997, although in that time only 11 executions were carried out at the site. From 1980 onwards, Pentridge housed the infamous "Jika Jika" unit, and was home to some of Australia's most dangerous contemporary criminals: Mark "Chopper" Read and the Russell Street bombers included.

When the prison closed in 1997, the corpses beneath were once again exhumed, this time undergoing DNA testing in hopes of reuniting them with their descendants. Although many former convicts were identified, it transpired that Ned Kelly's skull had been stolen away, and possible leads on its whereabouts still make news headlines today.

Today, there isn’t much left of Pentridge Prison. The southern part of the site has since been developed into the gentrified "Pentridge Village" residential area, while the last of the gaol's bluestone towers now rise out of parks and parking lots. Only the D Division of the former Pentridge Prison still stands in its original form, with a number of ghost walks offered by the local group Lantern Tours.

![article-image]()

The gates of Pentridge Prison, Coburg (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Security walls around the Pentridge site (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

D Division is the last remaining prison block at Coburg (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Security gates at D Division, Coburg (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Another atmospheric Victoria site is the former Aradale Mental Hospital in the rural town of Ararat. The hospital was originally known as the Ararat Lunatic Asylum, and it was opened in 1865 to care for a growing number of metal patients diagnosed within the Victoria penal colony.

The asylum closed in 1998, and in 2001 a wine college was built on one portion of the site. The remaining buildings have been preserved as a museum, including the much-storied "J Ward" which today entertains a regular stream of visitors on ghost tours.

![article-image]()

Ararat Lunatic Asylum, c.1880 (photograph by Victoria State Library/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

The J Ward building at Ararat (photograph by Rulesfan/Wikimedia)

There is another abandoned asylum in Victoria State, and one that has become a popular draw for tourists of an entirely different variety. Larundel Mental Asylum was built on the outskirts of Melbourne in 1938, and today this abandoned facility is a well-trafficked site amongst local street artists, photographers, urban explorers, and the usual stream of paranormal investigators.

The Larundel site at Bundoora was able to accommodate 750 secure patients in its heyday. It didn’t go straight into operation, but from the outbreak of WWII it served as a military hospital for five years and offered training grounds for WAAF operations. Even after that, the asylum buildings were used for a period as temporary post-war housing.

It was 15 years after construction that Larundel Asylum finally received psychiatric patients. The staff on site were equipped to deal with a range of conditions, specializing in acute psychotic and schizophrenic cases. In time, however, pharmaceutical treatments would start to replace the need for traditional institutional care, and Larundel finally closed its doors for good in the late 1990s.

Today this abandoned mental asylum stands in ruin. Parts of the site have been redeveloped, with 550 new homes appearing on the former grounds, but still the last few buildings remain. Largely derelict, these have become a popular destination amongst daredevil kids, as well as those practicing their photography or graffiti techniques. There are tales of hauntings, too — loud crashes, crying sounds coming through the walls, and most famously, the mysterious music box that can supposedly be heard playing in the asylum at midnight. According to the story, it belonged to a young girl who died at Larundel, and there are even videos on Youtube of visitors who claim to have documented the eerie phenomenon.

![article-image]()

The abandoned wards of Larundel Asylum (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Exploring the asylum (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

Larundel's last wards are facing demolition plans (photograph by Darmon Richter)

![article-image]()

The "haunted" ward on the third floor of the asylum (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Tasmania

The island of Tasmania is worthy of mention, having accommodated more than its fair share of the growing convict population of Australia. The first colony was established at Hobart in 1804, in what was then known as "Van Diemen’s Land."

That first gaol isn't there any more, but in 1821 it was replaced with the new Campbell Street Gaol. This maximum security prison was built using convict labour, designed in the Georgian Renaissance style. Following some later extensions, by its peak it was able to hold more than 1,200 inmates. Between 1857 and 1946, this Tasmanian facility saw a total of 32 executions.

As the population continued to grow, the site was replaced by the new Risdon Prison; by the early 1960s the prison's full population had been relocated away from Campbell Street. Most of the buildings were then destroyed. Today just a few of the old prison wards remain, managed for tourism by the National Trust.

In the 1980s the hanging scaffold was reconstructed for the benefit of visitors. Of particular note, though, is the Penitentiary Chapel Historic Site. This place of worship was built between 1831 and 1833, situated directly above a block of subterranean isolation cells. Some of Tasmania’s most notorious criminals were kept here at one point or another, including the English convict Mark Jeffery who was previously as a gravedigger on the Isle of the Dead at Port Arthur.

![article-image]()

Old Hobart Gaol on Campbell Street (photograph by Michael Thomsen/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

The chapel at Campbell Street Gaol (photograph by Michael Thomsen/Wikimedia)

Over on the west coast of Tasmania, the Macquarie Harbour Penal Station was established in 1820. It was situated on the remote Sarah Island and notoriously difficult to escape. In their desperation, convicts were reported to have drowned, starved, and in two documented cases, turned to cannibalism.

The Macquarie Harbour facility was replaced in 1830 by the colony at Port Arthur, and the buildings on Sarah Island were left to ruin. There’s little to see there today, other than a few collapsed stone walls and the outline of the former solitary cells.

![article-image]()

Sarah Island in Macquarie Harbor (photograph by M. Murphy/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

The remains of solitary cells on Sarah Island (photograph by Scott Davis/Wikimedia)

The newer Port Arthur prison was located on the Tasman Peninsula, some 35 miles southeast of the state capital at Hobart. This experimental "model prison" preferred solitary confinement over other forms of punishment, and in time earned a reputation as a particularly harsh and inhospitable destination for confinement.

Port Arthur was abandoned as a prison in 1877, and tourism followed fast. The location of the facility on the picturesque Tasman Peninsula certainly helped, and the newly built town of Carnarvon welcomed visitors who came for the local shooting, hunting, fishing and, of course, to marvel at the decaying ruins of the former prison colony.

By the 1970s, a great deal of work was put into preserving the site's striking sandstone architecture, the model prison, the chapel and guard tower in particular. In recent years even the Isle of the Dead — the site of the mass graves of executed prisoners — has been attracting a healthy stream of visitors, and Port Arthur survives today as Tasmania’s most popular tourist attraction.

![article-image]()

Port Arthur Penitentiary (photograph by Martybugs/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

Inside the prison block at Port Arthur (photograph by Jörn Brauns/Wikimedia)

![article-image]()

A convict-built church at Port Arthur (photograph by D. Gordon E. Robertson/Wikimedia)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The attack with the infernal machine illustrated by P. C. Geissler (1835) (via Bibliothèque nationale de France)

The attack with the infernal machine illustrated by P. C. Geissler (1835) (via Bibliothèque nationale de France) The infernal machine on display at the French National Archives (photograph by the author)

The infernal machine on display at the French National Archives (photograph by the author)

The infernal machine at the National Archives (photograph by the author)

The infernal machine at the National Archives (photograph by the author)

A decorative spirit wall blocks ghosts from entering the temple grounds (photograph by

A decorative spirit wall blocks ghosts from entering the temple grounds (photograph by  Erawan Shrine (photograph by author)

Erawan Shrine (photograph by author) Than Tao Mahaprom and his offerings (photograph by author)

Than Tao Mahaprom and his offerings (photograph by author) Winchester Mystery House (photograph by

Winchester Mystery House (photograph by  Hiji Castle (photograph by

Hiji Castle (photograph by  George Stickney House (photograph by

George Stickney House (photograph by Old Round Church (photograph by

Old Round Church (photograph by

All photos by Matthew Maye & Lynn Freehill-Maye unless noted

All photos by Matthew Maye & Lynn Freehill-Maye unless noted

Seychelles Fruit Bat on La Digue Island (photograph by

Seychelles Fruit Bat on La Digue Island (photograph by  Fruit bats flying in the Seychelles (photograph by

Fruit bats flying in the Seychelles (photograph by

Panteón Real de El Escorial (photograph by

Panteón Real de El Escorial (photograph by  Diagram of the Royal Pantheon (by

Diagram of the Royal Pantheon (by

Stairs down to the Pantheon (photograph by

Stairs down to the Pantheon (photograph by

Cherry the dog (photograph by the author)

Cherry the dog (photograph by the author) Cherry discovered by police (courtesy Sydney Justice and Police Museum archive)

Cherry discovered by police (courtesy Sydney Justice and Police Museum archive)

Skaterham (photograph by

Skaterham (photograph by  Bookstore patrons inside the Selexyz Dominicanen (photograph by

Bookstore patrons inside the Selexyz Dominicanen (photograph by  Selexyz Dominicanen (photograph by

Selexyz Dominicanen (photograph by  Aerial view of the Entreprenörskyrkan (photograph by

Aerial view of the Entreprenörskyrkan (photograph by  Entreprenörskyrkan (photograph by

Entreprenörskyrkan (photograph by  Exterior of the Monique-Corriveau Library (photograph by

Exterior of the Monique-Corriveau Library (photograph by  Rêver ("to dream") in the Bibliothèque Monique-Corriveau (photograph by

Rêver ("to dream") in the Bibliothèque Monique-Corriveau (photograph by  MareNostrum's glass box (courtesy of

MareNostrum's glass box (courtesy of  MareNostrum beeping away (courtesy of

MareNostrum beeping away (courtesy of

Church Brew Works (photograph by

Church Brew Works (photograph by  Sleigh Bells performing at Mr. Small's Funhouse (photograph by

Sleigh Bells performing at Mr. Small's Funhouse (photograph by Exterior of Mr. Small's Funhouse (photograph by

Exterior of Mr. Small's Funhouse (photograph by  South River Vineyard at sunset (photograph by

South River Vineyard at sunset (photograph by  South River Vineyard (photograph by

South River Vineyard (photograph by

The rarely-seen Cook fabric book (all photographs by the author unless indicated)

The rarely-seen Cook fabric book (all photographs by the author unless indicated)

John Cleveley the Younger, Captain Cook's voyage in Tahiti (1787-88) (via

John Cleveley the Younger, Captain Cook's voyage in Tahiti (1787-88) (via

The Museum of Everyday Life (all photographs by the author)

The Museum of Everyday Life (all photographs by the author)

A violin made of matches

A violin made of matches

Body snatching carved on a 19th-century tombstone (photograph by

Body snatching carved on a 19th-century tombstone (photograph by  Cedar Grove Cemetery in Augusta (photograph by

Cedar Grove Cemetery in Augusta (photograph by  Old Medical College Building in 2012 (photograph by

Old Medical College Building in 2012 (photograph by  1896 newspaper illustration of Chris Baker with a funeral director in the Medical College of Virginia anatomical theater (via

1896 newspaper illustration of Chris Baker with a funeral director in the Medical College of Virginia anatomical theater (via  Holden Chapel in 2007 (photograph by

Holden Chapel in 2007 (photograph by  Harvard Medical School in the 19th century (via

Harvard Medical School in the 19th century (via  University of Pennsylvania Medical School students with a cadaver (1890) (via

University of Pennsylvania Medical School students with a cadaver (1890) (via

Flak Bait sits piece-by-piece in the gigantic Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in Chantilly, Virginia (all photographs by the author)

Flak Bait sits piece-by-piece in the gigantic Mary Baker Engen Restoration Hangar in Chantilly, Virginia (all photographs by the author) Flak Bait close-up

Flak Bait close-up The Apollo Telescope Mount that was supposed to fly on Skylab, America's first space station.

The Apollo Telescope Mount that was supposed to fly on Skylab, America's first space station. A late 19th century print depicting an odd fish-like aircraft.

A late 19th century print depicting an odd fish-like aircraft.

The USS Enterprise

The USS Enterprise X-ray from the National Zoo

X-ray from the National Zoo

Our tour started at BLDG 92, a museum that showcases the history and innovation of the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Our tour started at BLDG 92, a museum that showcases the history and innovation of the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Approaching the former Naval hospital

Approaching the former Naval hospital

Water views from the Duggal Greenhouse

Water views from the Duggal Greenhouse The Navy Yard Hospital annex, to be

The Navy Yard Hospital annex, to be

Feast of St. Jude in Mexico City (all photographs by

Feast of St. Jude in Mexico City (all photographs by

Dancers at the Dance-O-Mat in Christchurch, New Zealand (all photographs by the author)

Dancers at the Dance-O-Mat in Christchurch, New Zealand (all photographs by the author) The remains of the Christchurch Cathedral, with the Chalice sculpture celebrating the city's 150th anniversary visible behind.

The remains of the Christchurch Cathedral, with the Chalice sculpture celebrating the city's 150th anniversary visible behind. Grace Cabell (left) and her dance partner, Sally Hoskin gear up to use the Dance-O-Mat.

Grace Cabell (left) and her dance partner, Sally Hoskin gear up to use the Dance-O-Mat. A Gap Filler sculpture in the same vacant lot across from the Dance-O-Mat.

A Gap Filler sculpture in the same vacant lot across from the Dance-O-Mat. Behind the lot, the ruins of a collapsed building have been walled off.

Behind the lot, the ruins of a collapsed building have been walled off. Downtown Christchurch

Downtown Christchurch Approaching Cathedral Square. This area may have seen more foot traffic around the time it was reopened in July 2013.

Approaching Cathedral Square. This area may have seen more foot traffic around the time it was reopened in July 2013. A mural just off Cathedral Square.

A mural just off Cathedral Square.

Flag Wall by artist Sarah Hughes, part of The Cathedral Square Project, offers a splash of color in the damaged Cathedral Square.

Flag Wall by artist Sarah Hughes, part of The Cathedral Square Project, offers a splash of color in the damaged Cathedral Square.

Oceans of Alabama (illustration by the author)

Oceans of Alabama (illustration by the author) The "Artemis" skeleton (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

The "Artemis" skeleton (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums) Harrell Station (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

Harrell Station (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums) Basilosaurus in the Alabama Museum of Natural History (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums)

Basilosaurus in the Alabama Museum of Natural History (courtesy Dana Ehret, Curator of Paleontology, University of Alabama Museums) Hydroarchos, archival image

Hydroarchos, archival image Basilosaurus (illustration by the author)

Basilosaurus (illustration by the author) Red Mountain Road Cut (photograph by

Red Mountain Road Cut (photograph by

Miranda Castle (all photographs by the author)

Miranda Castle (all photographs by the author)

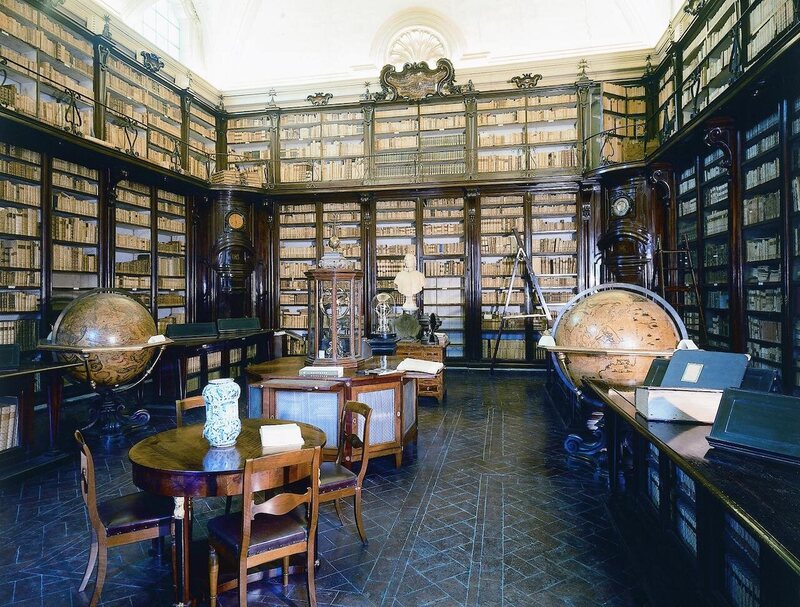

Biblioteca Vallicelliana (via

Biblioteca Vallicelliana (via  Società Geografica Italiana (photograph by

Società Geografica Italiana (photograph by  Palazzo Zuccari (photograph by

Palazzo Zuccari (photograph by  Photograph by Andrea Jemolo, © Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte

Photograph by Andrea Jemolo, © Bibliotheca Hertziana – Max-Planck-Institut für Kunstgeschichte Biblioteca Lancisiana (photograph by the author)

Biblioteca Lancisiana (photograph by the author) Biblioteca Lancisiana (photograph by the author)

Biblioteca Lancisiana (photograph by the author)

via

via  Teatro Dell'Opera (photograph by

Teatro Dell'Opera (photograph by  La Biblioteca "Luigi Chiarini" (courtesy Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia)

La Biblioteca "Luigi Chiarini" (courtesy Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia) Courtesy

Courtesy

The raw sugar warehouse of the Domino Sugar Refinery, which hosted a blockbuster Kara Walker exhibition prior to demolition

The raw sugar warehouse of the Domino Sugar Refinery, which hosted a blockbuster Kara Walker exhibition prior to demolition The packaging plant of Domino Sugar Refinery, now demolished

The packaging plant of Domino Sugar Refinery, now demolished The eerie abandoned office of Machpelah Cemetery in Queens, pictured in 2012.

The eerie abandoned office of Machpelah Cemetery in Queens, pictured in 2012. The burial site of legendary magician Harry Houdini is visible just beyond the gates.

The burial site of legendary magician Harry Houdini is visible just beyond the gates. The Yonkers Power Station looms over the Glenwood stop on the Metro-North line.

The Yonkers Power Station looms over the Glenwood stop on the Metro-North line. The perpetually flooded ground floor of the Glenwood Power Station was covered with a foot of Hudson River silt.

The perpetually flooded ground floor of the Glenwood Power Station was covered with a foot of Hudson River silt. The Gowanus "Batcave" as it appeared in 2013 just before renovations began.

The Gowanus "Batcave" as it appeared in 2013 just before renovations began. The top floor of the Bat Cave was one of the most impressive abandoned spaces in all of New York City.

The top floor of the Bat Cave was one of the most impressive abandoned spaces in all of New York City. Forty years of neglect left the Smith Infirmary looking like the quintessential haunted house.

Forty years of neglect left the Smith Infirmary looking like the quintessential haunted house. An ornate central staircase stands out from the rest of the devastated interior.

An ornate central staircase stands out from the rest of the devastated interior. Locals are fighting to save the façade of the Harlem Renaissance Ballroom from demolition.

Locals are fighting to save the façade of the Harlem Renaissance Ballroom from demolition. The ballroom's interior is said to be "beyond repair."

The ballroom's interior is said to be "beyond repair."