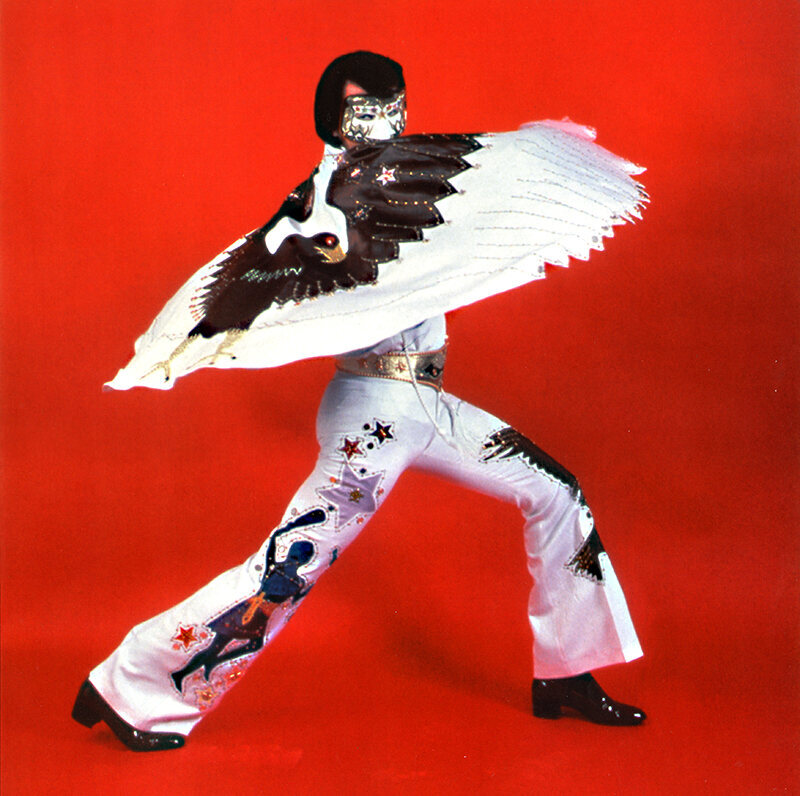

Orion is his iconic eagle suit. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion is his iconic eagle suit. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

When Elvis Presley died in 1977, the mourning that ensued was as fevered and earnest as the fandom that surrounded him in life. Thousands flooded Memphis to be near The King’s funeral, which was held at Graceland on a sweltering day on August 18th. People wept and reeled; they didn’t want to believe he was gone.

A year later, a masked man who called himself Orion gave them a very good reason to think he was not. He dressed like Elvis, he swiveled his hips like Elvis—and most importantly—he sang like Elvis. And not just a little bit: His sultry, resonant voice sounded exactly like The King. What incredible mystery was this man hiding behind the sparkly mask he never, ever removed?

At the core of Jeanie Finlay’s documentary Orion: The Man Who Would Be King is the story of a singer who is incredibly gifted but ultimately doomed because he isn’t one of a kind. It’s a problem a legion of musicians face, but in Jimmy Ellis’ case, it wasn’t so much that he couldn’t set himself apart from the crowd, it’s that he couldn’t untether his legacy from one of the world’s biggest music stars of all time. His voice was so similar to the icon’s, that the Ellis songs that comprise the soundtrack of Finlay’s film seem to be sung by Elvis’s ghost—and in a way they were.

Over several years and international reporting trips, Finlay pieced together the strange and tragic story of Ellis, a Tennessee crooner who hungered after fame and eventually found himself at the center of a bizarre marketing scheme that had him performing as Orion. He became a sensation; at times up to 500 fans would trail his tour bus. His fan club grew to 400,000 members, he released 9 studio albums, and he toured Europe, including a stint in Germany with Kiss. And while Ellis enjoyed many of the trappings of success, he suffered behind the mask and longed to be recognized for himself.

Finlay’s film is a meditation on the nature of fame, talent, and public persona, but it’s also an investigation into a pop cultural origin story that has largely been forgotten.

“I think Orion’s the reason that Elvis is still sighted today,” says Finlay. “They created a myth and let it just fester and grow in people’s imaginations.”

Orion: The Man Who Would Be King opens in the UK on September 25. We talked to Finlay about making the film, modern Orion fandom, and the nature of fame.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Director Jeanie Finlay. (Photo: Jo Irvine)

Director Jeanie Finlay. (Photo: Jo Irvine)

How did you find out about Orion?

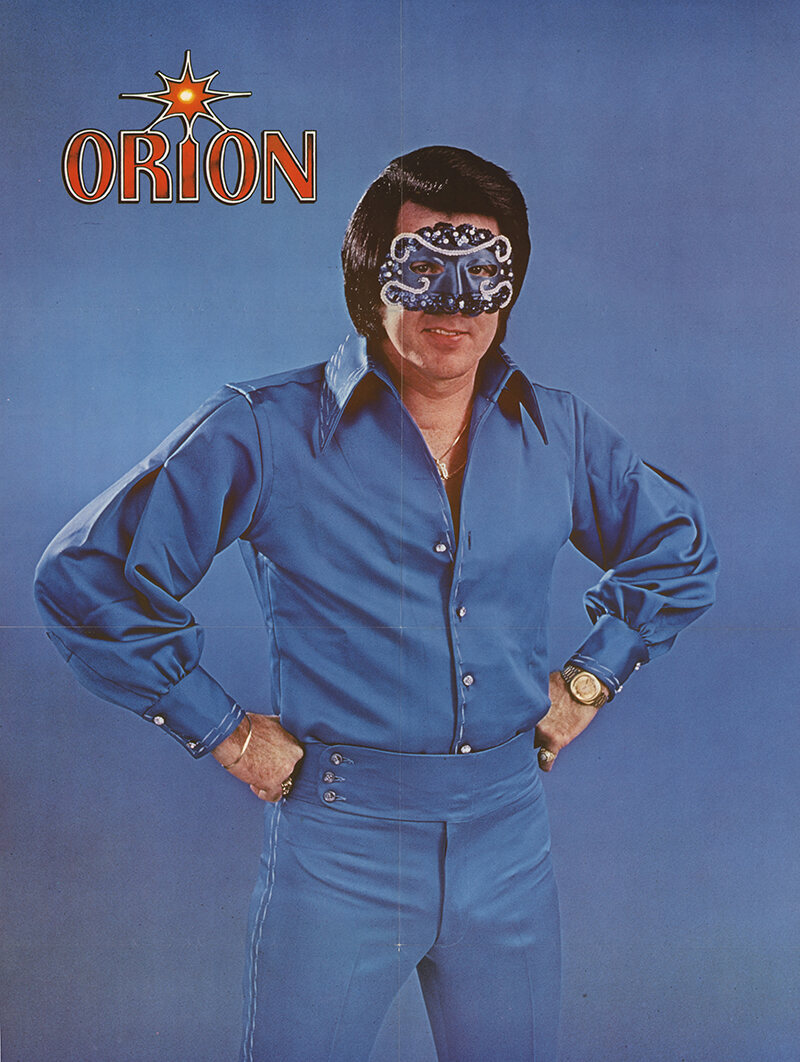

About 12 years ago, in Nottingham in England, where I live, I was at a garage sale with my husband and we bought an Orion record. It was “Orion Reborn”, so it was the reissued version. It’s a man in a blue suit on a blue background, so it’s a really striking album cover and he’s got really big hair and a mask and his hands on his hips. It’s just like ‘What is this!’

We buy a lot of records—I made a film about record shops a few years ago—we collect vinyl, lots of of old and interesting things. So we took it home and it was just like ‘What the hell is this?’ It had yellow vinyl, it’s gold vinyl, limited edition, and it sounded like songs Elvis might have recorded but you just never heard them. At that time I was making artwork, I wasn’t making films, so it was just this intriguing story. I researched into the back story and found out about his meteoric rise and then terrible fall. So it was a story that never really went away.

Then I started making films and I‘ve made a few features and I came back to Orion about six years ago and thought ‘Oh c’mon that’s got to be a film.’

And then I just gradually started to uncover it. It was a huge excavation job, because Orion was not a huge star. It was an intriguing story and there were definitely ways into it, but it was a mammoth job. I went to the states quite a few times, went to Norway and found the biggest ever collector of Orion material, he lives in Norway, so I went there twice. It was piecing the bits together and wondering, ‘Can this be a film?’ and I made three other features while I was making Orion.

It’s been a long time.

Orion from the album “Reborn” – the record that filmmaker Jeanie Finlay bought 10 years ago in Nottingham and set off on a quest to find the man under the mask.(Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion from the album “Reborn” – the record that filmmaker Jeanie Finlay bought 10 years ago in Nottingham and set off on a quest to find the man under the mask.(Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Was there ever a scenario where Jimmy could have found success or was his similarity to Elvis what doomed him from the beginning?

My belief is that he probably found the biggest success he could have, really. There’s a lot of very heated debate in Orion fan circles so there’s two schools of thought. One of them is that without the mask he wouldn’t have found any success and the mask was his ticket to stardom. And then the other school is that the mask got in the way and it stops him from ever becoming bigger.

I think that Elvis Presley cast such a long shadow over the whole career of Orion. It’s not like he sounded like Stevie Wonder. He sounded like Elvis, and he’s such an icon. There’s a whole industry in people trying to sound like him. I think it was really, really hard for him to ever be himself.

I think that’s the ultimate tragedy at the heart of the Orion story. He wanted to himself and be taken seriously and loved for himself. But when people heard him sing they didn’t think about what they had, they thought about what they’d lost.

Orion recording in the studio at Sun Records, Nashville. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion recording in the studio at Sun Records, Nashville. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

What does Orion fandom look like today?

I spent a lot of time in the eye of the storm of Orion fandom over the years. Orion fandom is very ardent. I haven’t done a screening yet where there isn’t a person there who’s a huge Orion fan. And I’d say because he’s pretty niche, the people who love him truly love and adore him.

So there are people that saw him back in the day in the south who are now maybe in their 60s and still play his music and still talk about his music every day...But then there’s also younger collectors. Kenneth [Dokkeberg, the Norwegian collector] is in his very early 30s and I think that for some people the idea of Elvis is that everything has been collected, every story has been told, every object has been bought. With Orion there’s new stories to discover and you can get close to the people that were in his band or you can buy things that he signed. He’s a more accessible star.

Promotional poster for Orion Reborn. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Promotional poster for Orion Reborn. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

You also made a film The Great Hip Hop Hoax about two Scottish musicians who pose as California rappers. What did making these two movies make you think about being famous and what being a star is. What’s the difference between having a persona and faking it?

I’m not sure that there is, really.

I think it’s made me feel quite cynical about everything but then I’m also drawn to the dream that people might make it. I keep thinking about The X Factor and The Voice and American Idol and those sorts of things. Every single person who goes on those programs thinks they’re going to break the mold and do it differently this time. And they don’t.

I think we all wear masks but Jimmy Ellis wore a spangly, sequined, bedazzled mask. And the boys in The Great Hip Hop Hoax—they were slightly different. They invented themselves. They could have been anyone they wanted and they created people that they didn’t even like. To me that was the whole thing, ‘Why would you do that? You could be anything.’ So that film’s really a bromance gone wrong.

(Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

(Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

And in the end Orion didn’t really like the persona he helped create, either.

Yes, but I would say he was more of a passenger, I think once Shelby [producer Shelby Singleton of Sun Records] got ahold of Jimmy that was it. I think he was much more passive in terms of creating his persona. I think he did it and obviously there was all the sex, he got all the women he ever wanted, all the perks to being a star, but it seems it always comes at a price.

Orion promo card put out by Sun Records. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion promo card put out by Sun Records. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion in London. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion in London. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Would it be possible to pull this off today?

I’m not sure. Another one of the things that drew me to the story was that it was to be discovered.

This is a story that lingers in people’s memories or in photo albums in attics of ladies in North Carolina or Alabama. So that was really intriguing to me—it was a sleeping story. This was a thing that caught fire by word of mouth, it was before Google. I’m not sure if it could happen now, at all. But you never know.

Orion from the album “Fresh”. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

Orion from the album “Fresh”. (Photo: Sun Records/Courtesy Pipoca Pictures)

I don’t know if it would be successful today because there’s a culture of glee in unmasking people.

Oh, definitely! He would have been discovered immediately. Immediately. They would have discovered it. I have to say though, even though all of that said, I still get loads of messages from people saying ‘You do know there were two Orions. One was Elvis and one was Jimmy Ellis.’ There are a lot of people who actually believe that he was Elvis. So I’ve said to them, ‘This is a documentary, it’s based on the facts I’ve unearthed and the people I’ve spoken to’ and then they don’t believe me anyway.

When the The Great Hip Hop Hoax came out, we were on the front page of Reddit because other people were calling it a hoax inside a hoax and it was a “hoaxception” and I was an actress. We played it at the Edinburgh film festival and afterward there was a guy who said ‘My girlfriend and I have discussed it all evening, and we’re confident that you’re an actress and so are the guys and this is all a tactic to sell records. Is it?’ And I said, ‘You can believe everything I’ve told you.’ And he said, ‘Well, of course you would say that.’

Once you make an atmosphere where people aren’t sure what is real, anything is up for grabs, really.