(Image: British Library/Public domain)

Shooting pool. Smoking cigars. Hanging out with a bunch of other divorced guys, crowing about being freed from the shackles of the ol' ball and chain.

Not exactly what you would expect to encounter during your average prison sentence, but that’s exactly what it was like inside the New York Alimony Club, a turn-of-the-century prison more formally known as the Ludlow Street Jail.

It was here that deadbeat ex-husbands who owed alimony would allow themselves to be jailed just so they could live it up while sticking it to their ex-wives. But even before all of that began, the Ludlow Street Jail, which crooked politician William “Boss” Tweed would both help found and later die in as an inmate, had a history full of extortion and corruption.

Overseen by the Board of Aldermen—including Boss Tweed years before he would get caught stealing millions of dollars from the city—the Ludlow Street Jail was constructed in 1862 on the corner of Ludlow and Broome Streets in lower Manhattan. The red-brick building with towering arched windows held 87 two-man, 10-foot-square cells, but did not look particularly menacing on the outside. The only real indications that it was a jail were the large iron doors and the crossed iron bars over the windows.

William "Boss" Tweed in the 1860s. (Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration/Public domain)

Though about 10 percent of Ludlow Street Jail inmates were serving time for federal crimes, the main population was there due to civic offenses—particularly unpaid debts. Debtors' prisons had been outlawed by the Federal Government in 1833, but claimants who could convince a judge that the debtor was a flight risk could, and often did, have the cheapskates locked up. Ludlow was also where people who defaulted on their alimony ended up, a trend that would later turn the jail into an unofficial clubhouse for divorced men.

Corruption ran rampant through the New York City government at the time, so it is no wonder that the Ludlow Street Jail slipped almost immediately into the world of back-door deals and shady habits. In a New York Times piece from November 4th, 1871, a Judge Barnard, in the process of discharging a number of inmates, was quoted as saying, “I’ve had occasion to look into the matter of Ludlow-street jail, and find that it is as well kept as any jail can be in the point of health and good treatment, [...] the chief in that department, Judge Brennan, is not only as kind and humane a man as any in the community, but is an honest man,” Of course this could not have been further from the truth.

In reality, Brennan was running the prison like a black-market hotel. In May of 1871, the New York Tribune arranged to have one of its reporters incarcerated in the Ludlow jail to check on some strange rumors about the facility. The reporter found that inmates were being offered better treatment and accommodations if they shelled out between $15 and $30 per week for the privilege. Inmates who couldn’t pay were trundled off to the top cramped top floors of the prison, where they were crammed into too-small cells where there often weren’t enough beds for everyone. Given that a huge majority of the inmates were dead-broke debtors, there was no way they could be expected to pay for this extortion.

On the other side of the coin, those who could afford to pay enjoyed a number of luxuries. In addition to kinder treatment and a general relaxation of prisoner restrictions, anyone who ponied up could play chess, smoke cigars, play billiards, and generally carouse like they were hanging out in a private gentlemen's club. Eventually, there was even a little market stall called the “Hole in the Wall” that was set up in one of the vacant cells.

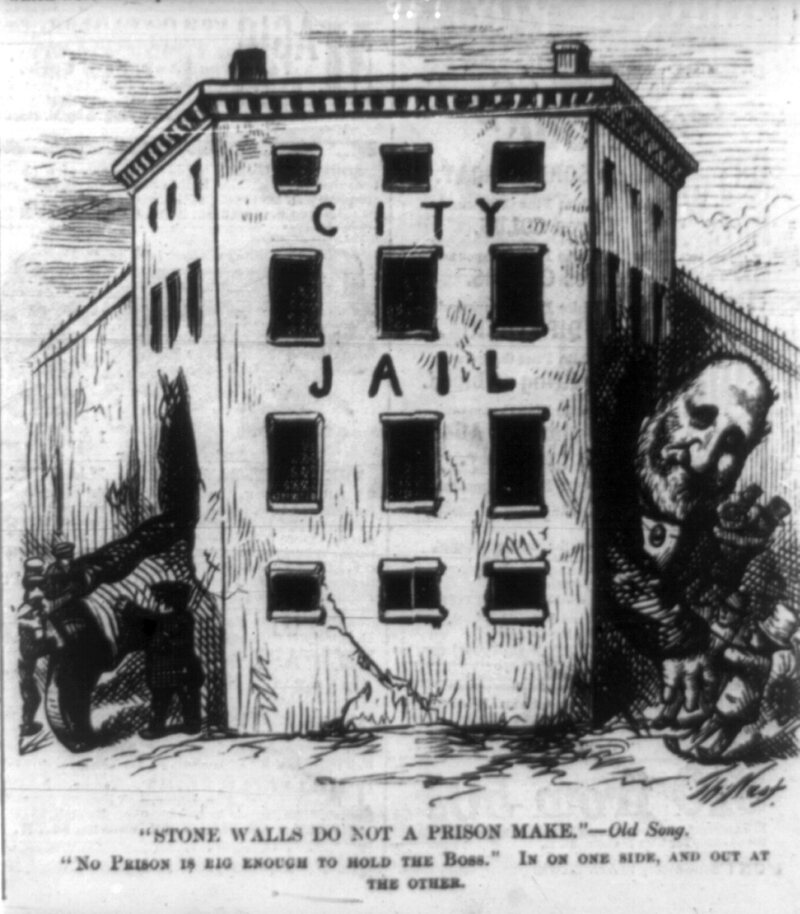

It was around this time that Boss Tweed’s political machine began to break down. His political schemes, through which Tweed had fleeced New York out of as much as $200 million, fell down around him. He was finally sent to Ludlow Street Jail after the city filed a civil suit in an attempt to recover some of the millions he had stolen.

Boss Tweed had it better than anyone while in the Ludlow Jail. For $75 a week, Tweed rented out the warden’s office and bedroom to use as his own luxury cell. In addition, and most bafflingly, he was allowed regular visits to his home. When he failed to return from one of these jail-sanctioned sojourns in 1875, one would be hard pressed to call it an “escape.”

Out on the lam, Tweed went to Spain, where he worked as a sailor. But there is a cost to being the boss, and that is fame. Thanks to Thomas Nast's cartoons of the disgraced politician being published in Harper’s Weekly, Tweed’s face had been spread far and wide. After someone in Spain recognized him and ratted him out to the U.S. authorities, they were able to pick him in 1876. Surprisingly, Tweed was once again placed in the Ludlow Street Jail. But before he could plan another not-so-daring escape, Tweed contracted pneumonia and passed away on April 12, 1878, still stuck inside the corrupt jail he helped create.

A Thomas Nash cartoon of Boss Tweed escaping jail. (Image: Library of Congress/Public domain)

Tweed’s death did nothing to stop the ingrained corruption of the jail. The institution had been under investigation for years, what with the seemingly endless stream of exposés and reports about the poor conditions and unfair treatment within. Efforts were made to reform the jail—the biggest and most influential of the changes, which happened in 1904, was to permanently remove the federal prisoners. The thought was that there was no need to keep harmless civic offenders in the same space as potentially hardened criminals, and removing the tough guys would free up some much-needed space.

In the early 20th century, almost all of the inmates left in the Ludlow Street Jail were men who had defaulted on their alimony payments. At the time, the laws in New York stated that if a man refused to pay alimony, he would be sentenced to six months in jail, after which he would be free of all further payments. Accordingly, divorced men whom the courts had decreed owed payments to their ex-wives began shrugging their shoulders and heading off to jail for an all-expenses paid vacation at what came to be nicknamed The New York Alimony Club.

Gone were the days of corrupt extortion. The days of gleeful misogyny had arrived. As one member of the club described to the New York Times in 1911, “Many of us have preferred to come here as a matter of principle rather than pay money that was demanded of us practically as black-mail from wives, who, while we were hard pressed, were living in luxury.”

The Alimony Club would host lavish holiday dinners for the inmates, and lived in a convivial little cabal—one that was “utopian,” according to the Times article. The new warden who arrived in 1912 even began playing music for the delinquent ex-husbands.

But the party did not last long. By the 1920s, the number of inmates enjoying their stay at the Ludlow Street Jail had dwindled to the point that the facility was of no more use to the city, and seemed more and more to simply be a financial albatross. The Alimony Club was disbanded with the closure of the jail in December 1927. In its place now stands Seward Park Campus, a collection of five small schools that each aim to inspire self-betterment.