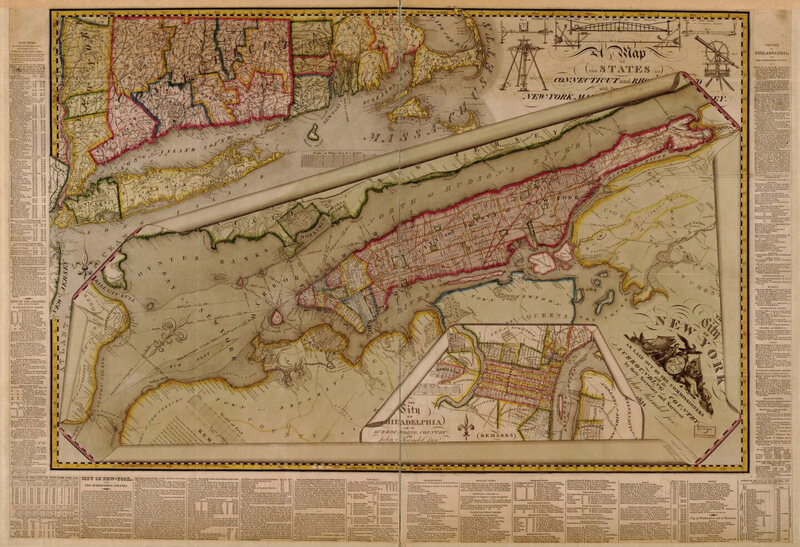

A street planning map from 1821 by John Randel. (Photo: Library of Congress)

If you’re going to complete this quest, bring a GPS tracker or have a damn good internal compass. Comb the southern area of Central Park and keep your eyes to the ground. Look for a rocky area and then scan the surfaces for an unnatural addition.

Connect the dots correctly, you’ll find a certain unmarked relic of which few are aware.

The discovery itself isn’t much to see. It’s merely a bolt — a long, jagged piece of metal that was battered into the ground some 200 years ago.

But it’s one of the last vestiges of lost New York that lives in plain sight without an official plaque highlighting its existence. And it’s become a popular treasure hunt for New York history enthusiasts and surveying hobbyists alike, a group of people who prefer not to divulge their knowledge of the relics' precise locations.

The bolt was hammered by John Randel Jr, the surveyor and brains behind the Manhattan Grid. In 1808 he was given the task of planning and commencing the beastly project of transforming the as-of-yet piecemeal-designed New York City into the modern gridded metropolis we know today. For years he surveyed and mapped his vision for the new city. Finally, in 1811 he submitted his designs to the city of New York.

A modern redrawing of the 1807 version of the Commissioner's Grid plan for Manhattan, a few years before it was adopted in 1811. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But that was the easy part. For nearly a decade he roamed the city, attempting to put either long metal bolts or monuments (three-foot by nine-foot marble slabs) into nearly 1,000 future intersections. These markers were the necessary precursor to actually building the brand new streets.

The work was painstaking and fatiguing, and Randel encountered numerous setbacks, according Marguerite Holloway’s book, The Measure of Manhattan. “Randel accidentally broke a screw on an instrument and had to travel to the city, 3 miles to the south, to have it repaired,” she writes. He also faced problems with accuracy. The obsessive man tried to ensure all of his measures for future city blocks were perfect. All north-south blocks, recounts Holloway, were to be 260 feet long, and yet one of his monuments just didn’t line up and he could not figure out why. This monotonous and grueling work went on for years—planting bolts and monuments, checking calculations, braving the elements—before any demolition was accomplished.

All the while, Manhattanites were not amused. Though the idea of a new and modern city may sound great to contemporary New Yorkers, people’s livelihoods were at stake with these changes. Houses were built on the soil of old New York and many of them were in the middle of Randel’s imagined streets. New Yorkers, thusly, protested. Some people destroyed Randel’s markers, others threw vegetables at him, one account claims dogs were released on the surveyor.

Though the city was supposedly giving these citizens pay-outs, the ultimate outcome was their land being demolished.

That’s why these bolts represent something deeper and more complex to Reuben Rose-Redwood, a professor of geography at the University of Victoria, than just a quaint keepsake of early New York. For his masters thesis, Rose-Redwood focused on the environmental history of New York City, and the changes the grid brought to the city and its inhabitants. To him, these bolts represent the “politics of mapping.” That is, their physical presence meant both a new modern city to Randel and other officials as well as assured destruction to landowners.

John Randel's survey bolt marked the location of Sixth Avenue and 65th Street; the location later became part of Central Park. (Photo: z22/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 3.0)

In 2004, Rose-Redwood and New York surveyor J. R. Lemuel Morrison trudged through Manhattan parks looking for possible places where the bolts could remain. Central Park seemed like the most obvious choice. It was not part of the original plan, which meant that Randel-planned intersections likely were forged into the ground and never materialized. Rose-Redwood and Morrison spent an entire summer, meeting up a handful of times, trying to find at least one of the bolts. Though the first attempts brought about a number of false positives — other landmarks that turned out not to be Randel’s actual marker—finally the two came upon a bona fide bolt the early surveyor had planted, likely the first time anyone realized what this piece of metal was. The trip got memorialized via a 2008 History Channel reenactment.

Following this, the release of Holloway’s book, and other events remembering the building of the grid, Manhattan history enthusiasts have become increasingly interested in the subject. But the beauty of the bolt is that it remains unmarked. And any true aficionado will never share the precise location, at least GPS-wise. Although, the general consensus is that this Central Park bolt is found at the imaginary intersection of 65th street and 6th avenue.

A surveyor bolt from John Randel Jr. (Photo: Marguerite Y. Holloway)

But it likely isn’t the only one. While Rose-Redwood and Morrison only discovered this one, other New York parks remain. More than a few enthusiasts have pored over Randel’s old maps where the bolts’ locations are marked and then search other parks. Online surveyor community forums have bragging posts where people show off their discoveries. Rose-Redwood too has received numerous emails over the years from people boasting their finds. While most of these discoveries are likely false positives, the professor believes at least one to be a true Randel bolt. “It looked almost identical to what we had found,” he said. So far just the Central Park bolt has been officially identified as one of Randel’s, but at least two others have been rumored to exist in other locations. One marble monument survived too— although not in its original location and was put on exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York in 2011.

As for any others, who knows? It may seem like every molecule of Manhattan has already been discovered and analyzed, but it’s easy to overlook a slab of metal unless you know its true meaning.