Robert the Doll, in close up. (Photo: Cayobo/flickr)

Here is something that most people would agree is true about Robert the Doll: He’s terrifying.

Ostensibly a little boy in a sailor suit, his careworn face is only vaguely human. His nub of a nose looks like a pair of pinholes. He is covered in brown nicks, like scars. His eyes are beady and black. He wears a malevolent smirk. Clasped in his lap he’s holding his own toy, a dog with garish, popping eyes and a too-big tongue lolling crazily out of its mouth.

Here are some other things that people also agree is true about Robert: That he’s haunted and that he has caused car accidents, broken bones, job loss, divorce and a cornucopia of other misfortunes.

Robert is 111-years-old and lives at the Fort East Martello Museum in Key West, Florida. Before that he was the property of Robert Eugene Otto, an eccentric artist and member of a prominent Key West family. (Yes, the doll and the owner had the same name, but the boy answered to “Gene”.) Robert was a childhood birthday gift from Otto’s grandfather, who bought the doll during a trip to Germany. Otto’s relationship with the doll continued into adulthood.

Haunted, right? (Photo: Courtesy Key West Art & Historical Society)

“What people really remember is what they would probably term as an unhealthy relationship with the doll,” says Cori Convertito, curator of the museum and Robert’s caretaker. “He brought it everywhere, he talked about it in the first person as if he weren’t a doll, he was Robert. As in he is a live entity.”

After some digging, the museum traced Robert’s origins to the Steiff Company, the same toy maker that first manufactured a Teddy bear in honor of Theodore Roosevelt. Robert was most likely never intended to be sold as a toy—a Steiff historian told the museum that Robert was probably part of a set fabricated for a window display of clowns or jesters.

“Which is kind of adorable,” says Convertito, “Especially with his impish behavior it kind of suits his personality really well.”

Robert’s little sailor suit was not supplied by the company; it was probably an outfit that Otto himself wore as a child.

More Robert. (Photo: Courtesy Key West Art & Historical Society)

According to legend, young Otto began to blame mishaps on the doll. While this could have been laughed off as childish storytelling, adults also started noticing odd occurrences, especially as Otto and Robert grew older. As an adult, Otto lived in a stately home he called “The Artist House”, where Robert could be seen positioned at the upstairs window. Schoolchildren swore that he would appear and reappear, and they avoided the house. Myrtle Reuter purchased the Artist House after Otto’s death in 1974, and also became Robert’s new caretaker. Visitors swore they heard footsteps in the attic and giggling. Some claimed Robert’s expression changed when anyone badmouthed Otto in his presence. Rueter said Robert would move around the house on his own, and after twenty years of antics, she donated him to the museum in 1994.

But far from banishing Robert to obscurity, his arrival at the museum marked a turning point for the doll.

Since Robert arrived, visitors have flocked to the museum to get a look at the mischievous toy. He has appeared on TV shows, he has had his aura photographed, he is a stop on a ghost tour, and he’s inspired a horror movie. He has a Wikipedia entry and social mediaaccounts. Fans can buy Robert replicas, books, coasters and t-shirts. And they can—and do—write to him.

“He gets probably one to three letters every day,” says Convertito. But they aren’t typical fan letters; they’re often apologies. Many visitors attribute post-visit misfortunes to failing to respect Robert (or even openly disrespecting him) and they write begging forgiveness. Others ask him for advice, or to hex those who have wronged them. Convertito says they have received around one thousand letters, which they keep and catalog.

Where Robert lives. (Photo: Courtesy Key West Art & Historical Society)

Robert also receives emails and homages. At some point, it became known that Robert had a sweet tooth so people leave and send him candy. Just recently he received a box containing eight bags of peppermints, a card, and no return address. (Exercising caution, the museum staff does not consume treats sent to Robert.) Guests leave him sweets, money and, occasionally, joints.

“It’s completely inappropriate,” says Convertito. “We are still a museum.”

Convertito is Robert’s caretaker—once a year she administers a check-up, taking him out of the case and weighing him to assess whether the humid Florida weather has adversely affected his straw-filled body. She is also his proxy, receiving and reading all his emails and letters and running his social media feeds.

In August she photoshopped Robert’s knobby face onto the now-famous picture of Kim Kardashian popping a bottle of champagne into a glass balanced on her behind. It was in order to attract attention to a campaign that would score the museum a grant if they garnered enough votes. Through the combined forces of Kardashian’s and Robert’s celebrity and the doll’s social media reach—he has almost 9,000 Facebook likes—the museum won by a “landslide”.

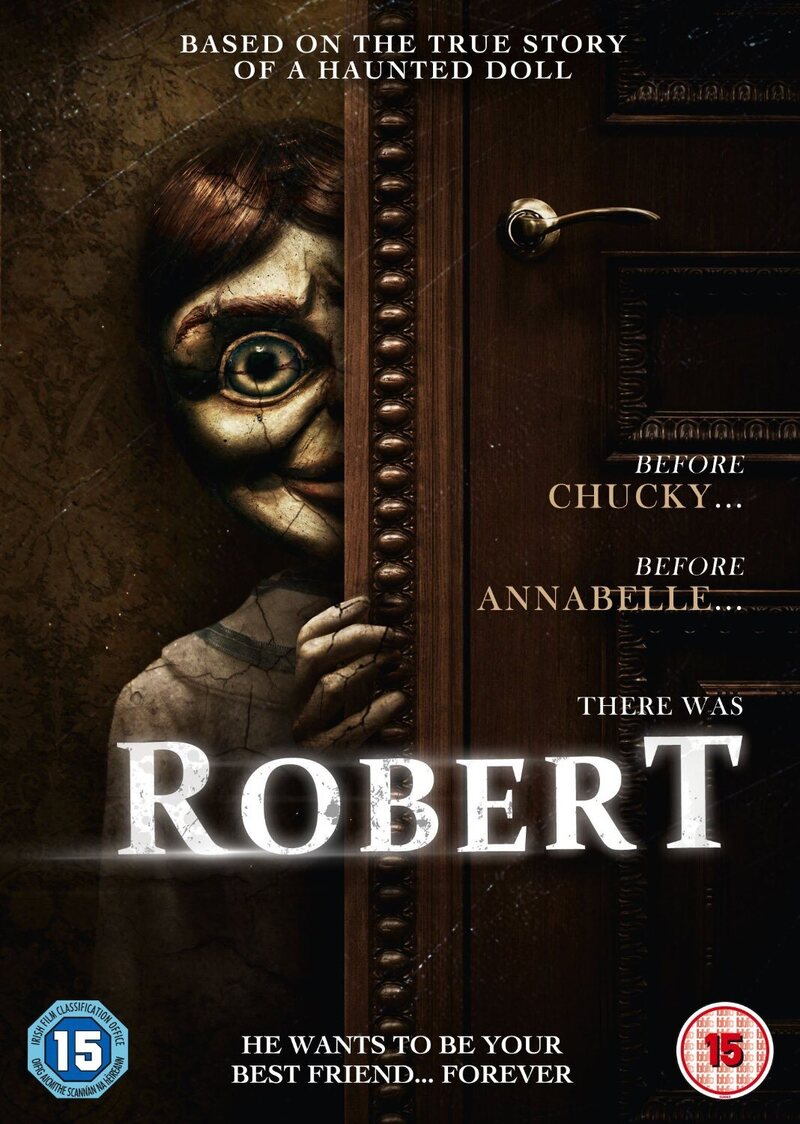

The 2015 movie based on Robert the Doll. (Photo: Courtesy of bttm.co.uk)

Occasionally, Convertito corresponds on Robert’s behalf. She tries to send something to every child who writes him (“Gene always had that childlike temperament around him and we feel like Robert would want to be kind to children.”) and she has also responded to more poignant ones, such as an email from a girl who was being bullied at school.

So, does Convertito think Robert is haunted?

“I don’t know. I really don’t,” she says. “I’ve never had a bad experience with him. I’ve never felt uncomfortable. It’s always been a very basic relationship and I have a job to do and I go and do it. And whether there’s something to it or not, he just allows me to get on with my job.”