Detail of a hologram on a German ID card. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

True story—a couple weeks ago, a restaurant attempted to deny me service because they thought I had a fake ID.

The ID was a few years old, granted, and it has a small crack in it, but it nonetheless was a real form of identification. The waiter made a joke along the lines of the ID looking like a fake ID he used in college, which seemed like a bad joke until a few minutes later, when the manager came out and asked to look at it. The guy claimed it was tampered!

This would have been the end of a 20-year-old’s fun night out, but considering that I’m 34 and was sitting with my wife for a quiet brunch, it seemed like an especially absurd situation.

But the fake ID racket has been going on for decades, and—to be fair to my waiter—there’s plenty of reason for alcohol-sellers to be skeptical. They could be dealing with the next McLovin'.

The world's first drivers' license, issued to Karl Benz upon his request, 1888. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

The history of the fake ID has much in common with other forms of secure information commonly held on a person. Credit cards are a good example: slowly, cards became such a common way that we paid for things that they had to eventually get more secure, because it became imperative to their growth. Likewise, if currency isn’t well-secured and counterfeits get into the monetary bloodstream, the whole system eventually fails.

And forms of identification are very much the same way. A century ago, identification was not even an issue at all, but the need to associate people with a specific identity started to become essential as automobiles became popular and alcohol became more heavily regulated. A driver’s license is sort of a de facto way of checking someone’s age, but even that took some time to become formalized—many states didn’t even require that licenses had photos before the 1970s.

Fake IDs are often seen as a relatively recent phenomenon as a result, but there are at least a few examples of people using fakes as early as the ‘70s.

For example, Kurtis Blow, an early hip-hop star, used a fake ID to his advantage in starting his music career. While his classmates were still in school, Blow was getting to know DJs around New York City as early as 1972.

“When I was 13 I had a fake ID that said that I was 19. I was getting in all the clubs,” Blow explained in an interview.

That networking paid off by 1980, when Blow became the first rapper to have a gold-selling single, the first rapper to perform overseas, and the first to sign to a major label. He did all of this before his 22nd birthday.

A saloon in Charleston, Arizona in 1885, in the days before any minimum drinking age, and when a bouncer's job was just to forcibly eject brawlers. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

At the time that Blow was coming up, his situation was a relative rarity; fake IDs weren’t so much a big thing back then in part because a number of states had laws that had set the drinking age at 18, something done in response to the fact that many teenagers could vote and legally be sent to war at that age.

Eventually, though, that changed, and it’s all thanks to a clever law.

Much like the book 1984 was a turning point for dystopian literature, the year 1984 was a turning point for the rise of fake IDs. That year, New Jersey Sen. Frank Lautenberg teamed with Mothers Against Drunk Driving to get the National Minimum Drinking Age Act passed.

The law was a clever workaround of the 21st Amendment, which didn’t allow for federal regulations of drinking. See, Lautenberg’s law doesn’t require a drinking age, per se, but states that have a drinking age below 21 automatically lose 10 percent of their highway funding, which is a nice strategy for strong-arming states into compliance.

Now, there were sound reasons for the law—specifically, the rise of automobile crashes caused by drunk drivers was directly related to the lower legal age limits in states with lower drinking standards. There were also sound reasons against it—the fact that people who can legally vote and be sent to war can’t buy a Natty Boh on their own accord. Nonetheless, the law had the effect of boosting interest in the creation of fake IDs.

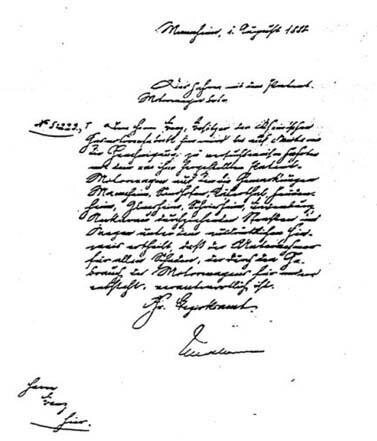

Much like dollar bills began to start looking like works of avant-garde art in the early '90s, state-issued IDs began adding all sorts of crazy gizmos to discourage fakery. Photos were an obvious step, one that many states started adding in the 1970s. In recent years, states have started using holograms, moving from plastic to laminate, adding barcodes and other digital features, and hiding ultraviolet pictures inside of the cards.

The more crazy stuff you put on the card, the harder it is to fake. To give you an idea, this is what California’s driver’s license looks like these days.

Why are these cards so over the top nowadays? Simply put, it’s become clear, as security has become a much bigger issue around the world, that the rise of fake IDs represents a lot more than a few extra PBRs given out to kids under the age of 21. They also can (depending on who you ask) lead to a loss of tax revenue, a flood of unauthorized immigration, and potential threats to national or international security.

That last one shouldn’t be taken lightly, by the way: After the disappearance last year of Malaysia Airlines flight MH370, there was a brief freakout when Interpol realized that two of the passengers had used forged passports. Those people were merely asylum-seekers from Iran, but it nonetheless highlights the risks fake IDs can create.

Those who use fake IDs are also putting themselves in great risk of legal action: In some states, such as Florida and Illinois, usage of a fake ID is a felony offense.

A board advertising fake IDs in Thailand. (Photo: 1000 Words/shutterstock.com)

These days, the fake ID game is a bit of an arms race: As real IDs have improved, so too have the strategies used by the creators of fakes.

Guides on how to make your own fakes—noting the usage of materials like Teslin paper, hologram overlays, and magnetic stripe encoders—are rampant all over the internet, but the complexity of creating an ID of this nature on your own is way beyond the knowledge of any Photoshop expert. Just because you can cut out an image doesn’t mean that you can make a realistic-looking ID.

It’s probably a good idea, then, to leave it to the internet experts. In recent years, the Reddit community /r/FakeID has become a key source for acquiring these handmade works of art. People around the world are willing to risk potential arrest and prosecution to create these cards, but often the financial rewards—often paid out in cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin—make the risk worthwhile.

The community is pretty good at policing itself, with a list of verified vendors and scammers right at the top of the page.

Beyond the Reddit community, the primary driver of the fake ID business these days is China, where businesses of questionable legality ship IDs inside of small packages to college towns across the country. The quality of these IDs is so good that they sometimes fool the experts.

The import of fake IDs is common enough that customs officials are keeping an eye out: Between October 2013 to September 2014, authorities at Kennedy International Airport confiscated 4,585 fake IDs, most of them from China. Why has it become so common? Simply put, it’s harder to prosecute people committing fraud half a world away in countries where the specific crime isn’t even illegal.

One advocacy group, the Coalition for a Secure Driver’s License, has been one of the biggest critics of the rise of fake IDs from China, which it says raise security issues and threaten lives. In a USA Today op-ed earlier this year, the group’s director of research, Max Bluestein, said that the U.S. Department of Homeland Security needs to work with the Chinese government to stop the spread of fake IDs from the country.

“The driver’s license is fundamental to our security infrastructure. While Chinese companies are flooding our borders with these counterfeits, that infrastructure is in danger of crumbling,” Bluestein wrote.

The new California license. (Photo: dmv.ca.gov)

By the way, it’s worth pointing out that—even if you have a high-quality fake ID—there’s a good chance that the bouncers at the bar or counter slaves at the liquor store will be able to easily figure out that it’s not real. Because they’ve seen it all.

“If an ID is from Wilmington, Delaware, it’s fake 100 percent of the time. Wilmington, Delaware is the hands down, all star of fake IDs,” a New York City bouncer wrote on Jobstr back in 2013.

And they can spot trends better than you can. Earlier this year, a Maryland grocery store stopped accepting Connecticut IDs because they were seeing so many fakes—high-quality fakes that managed to include perfect holograms of the state’s seal. The one stop to all of this production could be biometrics becoming more integrated in ID technology—but while that's on the way, it hasn't quite arrived yet.

Perhaps that’s what happened to me at that restaurant I went to a couple weeks back: They had seen so many IDs that were fake that they assumed a 34-year-old married guy with a beard and an appalling lack of common sense was trying to pull a fast one on them.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.