Laksa is said to get its name from the Sanskrit word "lakh," which means 100,000. (Photo: InterContinental Hong Kong/Flickr)

A few things are definitive of an afternoon on the coasts of Southeast Asia: inescapable heat, the smell of the sea, and a steaming bowl of laksa. If you haven’t been fortunate enough to sample laksa before, picture an addictively spicy noodle soup brimming with chillies, coconut milk, tamarind and fresh seafood. If you need additional convincing, laksa was ranked seventh on CNN’s list of the World’s 50 best foods in 2011.

There is nothing quite like laksa, and no two laksas are the same. The soup can be found in different iterations in four Southeast Asian countries, from the coasts of Thailand and Malaysia down to Singapore and Indonesia, but its origins are more elusive. Where did laksa really come from, and how did it spread through all the regions that now claim it as their own?

To begin tracing the laksa trail back through time, we need to plot its three modern variations—curry, Siamese, and Assam—on the map.

Curry laksa is spicy and likewise includes coconut milk. It is found in Malaysia's Malacca and Johor states, and pops up in Singapore as Katong laksa, and in Indonesia as Bogor, Cibinong and Betawi laksa, to name a few. Each region has added its own unique ingredients to the mix, such as kaffir lime leaves, shredded chicken, or even snakehead fish.

Curry laksa. (Photo: Alpha/Flickr)

Siamese laksa, found in Thailand, contains coconut milk and is informed by traditional Thai flavors such as red curry paste, while Assam laksa (which has tamarind but no coconut milk) is found in the Penang state of Malaysia.

Assam laksa. (Photo: Alpha/Flickr)

Because of all the different varieties, it’s difficult to say whether laksa had a specific point of origin. The history of Southeast Asia has been one of trade, with the port cities of Singapore, Malacca and Penang being major stops along the spice route. As a result, laksa began popping up in multiple regions as the marriage of different cuisines brought over by traders.

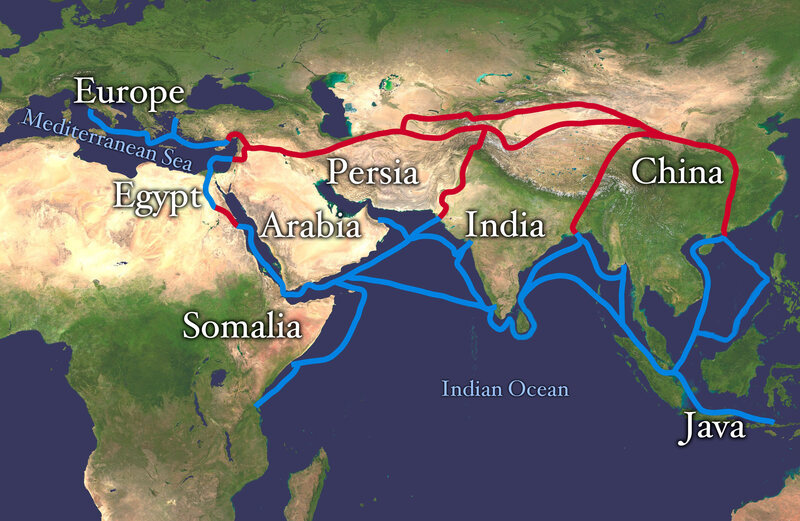

A map showing the Silk Road in red and the spice trade routes in blue. On the right, the routes stretch from India down through the Strait of Malacca, past Singapore and Indonesia and up to China. (Photo: Public Domain/Wikipedia Commons)

Southeast Asia had an early period of intense interaction with China and India, which largely influenced the culture of the region, and therefore its cuisine. According to Professor Penny Van Esterik in Food Culture in Southeast Asia, Indian traders arrived in Southeast Asia as early as 200 BC, while the Chinese had settlements in Indonesia by the 16th century.

The descendants of these Chinese traders were called the Peranakans, and the tradition of laksa was born out of the Peranakan desire to marry Chinese food with existing Southeast Asian flavors like coconut milk, and those brought over by South Asian traders, like chillies. Often, the desire to marry cuisines resulted from literal marriages between Peranakans and locals. In Indonesia, for example, the origin story of laksa traces back to the Chinese coastal settlements. Chinese sailors set out to find local wives, and these women began incorporating chilli peppers and coconut milk into Chinese noodle soup. Similarly, the arrival of laksa in Malaysia can be traced back to marriages of Chinese traders to local women in Malacca in the early 19th century.

A Peranakan wedding takes place in Penang, Malaysia in May 1941. (Photo: Public Domain/Wikipedia Commons)

In Singapore, laksa arrived in the town of Katong when the Peranakans travelled down to the island from the Malaysian peninsula. Southeast Asian food expert Dr. Jean Duruz followed a laksa trail in Singapore to uncover that Peranakan laksa evolved with interaction with local Singaporeans. This happened via “[t]raditions of working for, or 'marrying into,' Peranakan families" as well as "rituals of exchange of festive foods and recipes between neighbors,” writes Duruz in The Taste of Retro: Nostalgia, Sensory Landscapes and Cosmopolitanism in Singapore.

Of all the food that the Peranakans brought with them, it was laksa that spread most rapidly and extensively through trade channels in Southeast Asia. Why? Laksa's wide popularity is largely due to its adaptability, which makes it an appealing meal across many cultures and contexts. Even the name itself metaphorically empowers laksa’s cultural flexibility. The word “laksa” originates from the Sanskrit word for one hundred thousand, and refers to the large variety of ingredients used in making the dish. Local women were able to manipulate the noodle soup brought over by their Chinese trader husbands to include their own plethora of existing ingredients. Because laksa was so easily adaptable into new varieties, it was able to serve as a bridge between cultures when traders and locals began intermarrying.

“The successful story of Laksa challenges the idea that people always like to eat familiar food,” writes Veronica Mak Sau Wa in Southeast Asian Chinese Food in Hong Kong. There is nothing quite like laksa, and no two laksas are the same. Its unique adaptability is why it was able to build bridges between traders and locals on the Southeast Asian spice routes and continues to cross new borders today.