Graffiti in Québec which roughly translates to "We don't give a fuck about the special law (Bill 78)". (Photo: Gates of Ale/CC BY-SA 3.0)

Québec is bilingual, but reluctantly. As a French province with small pockets of English, and a few larger pockets that will willingly use both languages, the signs, by law, are in French. The language on the street is French. Ordering food or browsing a store will likely involve some amount of standard conversational French, and should you get in trouble with the law, it's going to be time to find a Francophile lawyer.

The profanity, though, is pure Québec.

Québec's swearing vocabulary is one of the weirdest and most entertaining in the entire world. It is almost entirely made up of everyday Catholic terminology—not alternate versions, but straight-up normal words that would be used in Mass to refer to objects or concepts—that have taken on a profane meaning. Many languages have some kind of religious terminology wrapped into profanity (think of English's "damn" or "goddammit"), but Quebec's is taken to a totally different level.

A snowy street in Montréal, looking towards the Notre Dame de Bonsecours Chapel. (Photo: Jazmin Million/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The fact that the region has unique swears is not itself unusual. Expletives are a curiously organic construction; despite the taboos and restrictions around using them, they persist, indicating a weird discrepancy. They are bad, yet we must have them. They change over time; during the age of Shakespeare, the word "bastard" was so foul that it was sometimes censored as “b-d”. Yet now, in the U.S., it's a low-level swear at worst. Different languages and cultures develop their own library of swear words, and just how that happens can tell you quite a bit about that culture.

"I have heard that people swear with the things they are afraid of," says Olivier Bauer, a Swiss professor of religion who taught at the Université de Montréal and lived in the city for a decade. "So for English speaking people it's sex, in Québec it is the church, and in France or Switzerland it is maybe more sexual or scatalogical." Fear and power kind of tie together; swear words tend to be words that invoke something mysterious or scary or uncomfortable, and by using them we can tap into a bit of that power. (Yiddish, the swear words of which I grew up hearing, has about a dozen curses referring to the penis. I'm not sure which category that falls into.)

Québec French is mutually comprehensible with European French, but due to its isolation from Europe and geographical proximity to Anglophone Canada and the U.S. has developed into something a bit different. Without constant interaction with France (or Switzerland or Belgium, for that matter), Québec French has retained French words that have long since gone out of style in France, but has incorporated and mutated many English words that a Frenchman would likely not recognize. In France, a car would be referred to as a voiture, maybe an auto. In Québec, it's a char, an ancient word coming from the same root as the word "chariot."

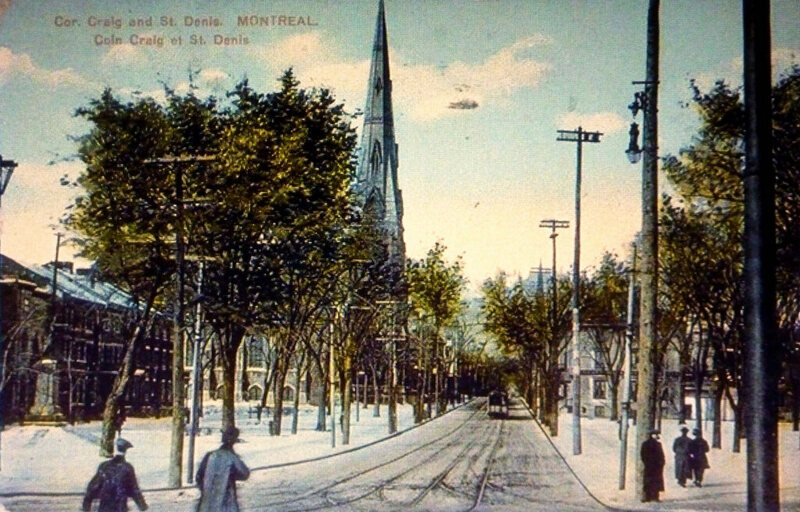

Montréal, c. 1910. (Photo: Philippe Du Berger/CC BY 2.0)

Similarly, Québec has adopted whole bunches of North American English, but those aren't just English words pronounced with a Québec accent; they are sometimes mutated and their meanings even change. Some are just spelled differently; moppe in Québec French means "mop," and toune can mean a song, or a tune. "The noun blonde can be used on both sides of the Atlantic in the sense of a blonde-haired woman, but in Québec, it has the additional meaning of 'girlfriend,'" says Felix Polesello, the proprietor of Quebec language blog OffQc. "For example, ma blonde means 'my girlfriend.'"

Then there's a phrase like this, which I saw on a friend's neighbor's front door once: "La doorbell est fuckée." The word "fuck," for the record, is fairly common in Québec, but isn't really a swear; it's a mutated form of an English, but it's only barely rude, meaning "broken" or "messed up."

Québec has few swears that you'd also find in France. Merde, maybe. I've heard enculer before, which means something like the verb "to fuck" and is usually paired with something else to enhance it. But the best swears are the sacres.

The sacres is the group of Catholic swears unique to Québec. There are many of them; the most popular are probably tabarnak (tabernacle), osti or hostie or estie (host, the bread used during communion), câlisse (chalice), ciboire (the container that holds the host), and sacrament (sacrament). These usually have some milder forms as well, slightly modified versions that lessen their blow. "For example, tabarnouche and tabarouette are non-vulgar versions of tabarnak, similar to 'shoot' and 'darn' in English," says Polesello.

The stained glass window in Notre Dame de Bonsecours Chapel. (Photo: daryl_mitchell/CC BY-SA 2.0)

The sacres typically are interchangeable, rarely having any particular meaning by themselves. Most often you'll hear them used as all-purpose exclamations. If a Québecois stubs his or her toe, the resulting swears might be "tabarnak, tabarnak!" instead of "fuck fuck fuck." They can be inserted into regular sentences the way English swears can to vulgarly emphasize your statement. "For example, un cave means 'an idiot,' but un estie de cave means 'a fucking idiot,'" says Polesello.

Because the words are largely just meaningless statements of rage, there is an interesting ability in Québec French to create fantastic new strings of profanity that are, basically, untranslatable. Essentially you can just list sacres, connecting them with de, forever. Crisse de câlisse de sacrament de tabarnak d'osti de ciboire!, you might say after the Canadiens fail to make the NHL playoffs. The closest English translation would be something like "Fucking fuck shit motherfucker cockface asshole!" Or thereabouts. But strings of profanity like that in American English, though not unheard of, are certainly not common. In Québec, letting loose with a string of angrily shouted Catholic terminology is something you're fairly likely to hear at some point.

So how did Québec end up with such a specific brand of swearing? "Without a doubt, the social institution that exercised the greatest influence, and had the most impact on Québec, was the Roman Catholic Church," writes Claude Bélanger, a historian at Montréal's Marianapolis College. When Québec was founded, in the early 1600s, the French Catholic Church played a huge role in its creation, building cities, forcibly converting the First Nations peoples who lived there, and controlling all community services until France officially made Québec a French province in 1663. Québec was ceded to Great Britain after the Seven Years' War in the mid-1700s, but the people of Québec continued to speak French and to take great pride in their French heritage.

Having a mostly secular government began to erode the popularity of the Catholic Church in Québec, until the Rebellions of 1837-1838. These were not dissimilar to the U.S. War of Independence, with the added wrinkles that English and French Canada were not especially friendly, and that the revolts failed. After the rebellions fell apart, martial law was declared in Montréal, and with turmoil all around them, the Québecois began to look to the organization that had always been there: the Church.

A mailbox with Québec French that roughly translates to "No fucking admail". (Photo: Gates of Ale/CC BY-SA 3.0)

"I think the second half of the 19th century, that's when it became omnipresent," says Bauer. The number of Catholic congregations in Québec skyrocketed. The Church all but took over social services yet again, from education to marriage. The dominance of the Catholic Church in Québec went on far longer than anywhere else in North America, and indeed most places in Europe. Over 90 percent of the Quebec population regularly attended Catholic church services right up until 1960. Catholic newspapers flourished. Catholic schools became the vast majority of the sources of primary education in the province.

In 1960 that all changed; the election of Jean Lesage as the premier of Québec found the province beginning what would come to be known as the Quiet Revolution. Secularization began in earnest as education was wrenched out of the hands of the Church through various means (standardizing curriculums, replacing Catholic secondary education with a pre-college school system known as CEGEP), and industries ranging from energy to mining to forestry were created as public institutions, undermining the Church's power.

This is all to say that the reason Québec developed the sacres is that in few other places was the grip of centralized religion quite so firm. But with the lessening prevalence of Catholicism in Québec, it's not at all clear that the sacres will survive. "It's still there but the young people like to use fuck, or son of a bitch, those are young kind of trendy, American slangs," says Bauer. Even weirder: without the Church in their lives, some young people very literally do not know what the sacres mean. "Among the young generation nobody knows exactly what hostie or tabarnak is, but it's still the heritage in Québec culture." The younger generation may still use the words because their parents and grandparents use them, but some of their power is lost.

That's totally unlike, say, "fuck," which has been a powerful word for hundreds of years. The power of sex never lessens, but the Catholic Church? That can ebb and flow. At a certain point, there's a possibility that the Québecois may decide that there's nothing especially powerful about a tabernacle. And then tabarnak will be nothing more than a box.