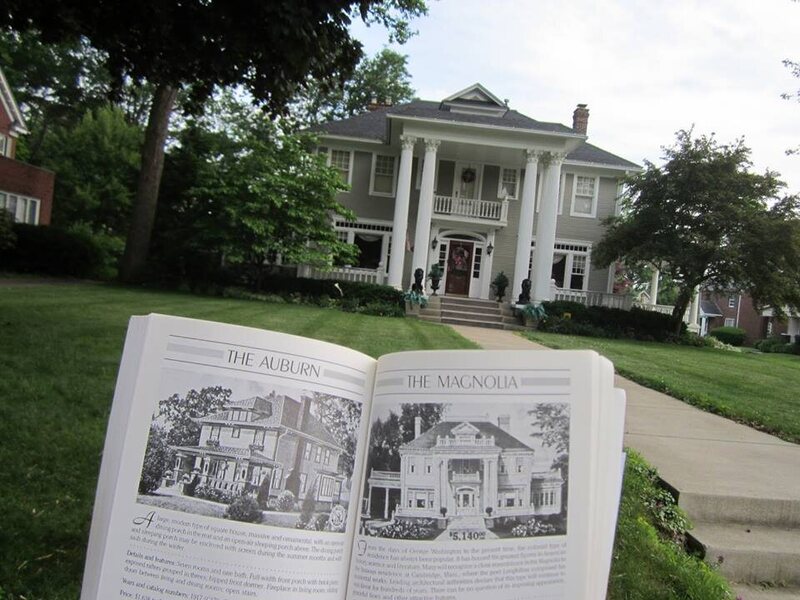

Great find—a Sears "Magnolia" in Canton, Ohio, and its catalog listing. Enthusiasts call the Magnolia the "holy grail of kit houses." (Photo: Courtesy Andrew and Wendy Mutch)

This past Monday, a car rolled through Fort Wayne, Indiana and pulled up outside a decidedly average-looking house. The home was one-story, flanked by two small porches, its peaked roof held up by brick columns. Inside were a living room, a couple of bedrooms, and a kitchen. To the untrained eye, it was a charming but ordinary bungalow.

The eight trained eyes inside the car widened in excitement. The four people they belonged to began murmuring and snapping pictures. One of them, Andrew Mutch, poked his head out of the car window, just as the confused homeowner opened the front door. "Hey there!" he hollered up the lawn. "Is this a Sears Kit House?"

Sears, Roebuck & Co. are best known as purveyors of farm equipment and home appliances. Even today, it's easy enough to imagine outfitting an entire house, basement to bedroom, from a Sears catalogue. But from 1908 through 1940, the company went a step further: they sold entire DIY house-building kits.

Also known as "Sears Modern Homes" or "Sears Catalog Homes," these houses were bought straight out of a mail-order booklet, under 447 different names and designs—from the stately, two-tiered Lexington to the tiny, beach-ready Goldenrod. They came precut and ready to assemble, like extremely ambitious Ikea kits. "We will furnish all the material to build this," Sears Kit House listings promise, from lumber and building paper all the way down to shingles, siding, and seating for the breakfast alcove.

A 1920s catalog listing for the Hamilton. (Image: Catarina Bannier/DC House Cat)

Andrew and his wife, Wendy are part of a growing cadre of kit house hunters. For years, they have spent their free time driving around the Midwest, casing neighborhoods for the distinctive homes. Their introduction came through purchasing a kit home themselves (a1926 bungalow called a Hamilton with oak trim and a giant fireplace) in Novi, Michigan. Since learning about their house's history, they treat every road trip as an excuse to expand their repertoire.

Last year, they drove all the way to Ohio to pose in front of a Magnolia, the largest model Sears offered, and what Mutch calls the "holy grail of kit houses." This Memorial Day found them attempting an exhaustive survey of Fort Wayne, along with two other experts, Dale Wolicki and Rebecca Hunter. "We're junkies down here," Mutch says with a laugh.

Luckily for them, the country is chock full of kit houses. Sears sold 75,000 kits to customers in every state and clear up to the Canadian border. Other companies, like Aladdin and Gordon Van Tine, got in on the action with their own lines. Mutch estimates that 70 percent of Sears houses are still alive and kicking, thanks partly to their resilient materials, which include old-growth timber and high-caliber furnishings. The Mutch family's Hamilton still sports its original wood-frame windows, now 90 years old.

Andrew and Wendy Mutch's Hamilton kit house, today. (Photo: Courtesy Andrew and Wendy Mutch)

The way Mutch describes it, kit house hunting is a bit like birdwatching. First—before you even set out—you have to narrow your range. Despite the homes' ubiquity, some regions are better stocked than others. Cities where Sears or its affiliates had big factories, like Cincinnati and Newark, are especially flush.

Once you've got your region, it's time to to zoom in further, searching for the kit house's preferred habitat. Proximity to a railroad is helpful, as the parts were delivered via boxcar. So are neighborhoods with a long middle-class history—communities that, as Mutch puts it, "are kind of in-between," where kit houses are protected from both upsizing and urban decay. Because Sears sometimes helped their homeowners out with mortgages, more clues can be found in archive offices, and traced back to street addresses.

After that, it's mostly a matter of driving around. Kit house hunters tend to cruise with a camera and a copy of Houses By Mail, which is essentially the Sibley of Sears houses—an exhaustive 1986 guide that contains descriptions and pictures of nearly every model the company put out. Get familiar enough, and you can drive-by spot them. "There's quite a few that we can recognize," says Mutch, even after just a few years in the game.

The cover of the 1914/15 Sears Modern Homes catalog. (Image: Rachel Shoemaker/Oklahoma Houses By Mail)

Once a specimen is located, the Mutches photograph it from as many angles as they can muster without trespassing. They'll introduce themselves to curious homeowners—many people don't realize they live in kit houses. (If you think you might, look for stamped lumber, shipping labels, and "SR" marks on your plumbing.) Occasionally, they'll even get tours. Then, they move swiftly along. "There's always more houses," says Mutch.

For the unschooled, it can be hard to identify a kit house. Rather than make up new designs, kit house companies generally just parroted existing ones. When Victorians were in vogue, they started offering styles like the 303. When bungalows were in, they jumped on that bandwagon, too. "They were based on popular styles of the day, just like clothing," says Rachel Shoemaker, who has collected, organized, and pored over kit house catalogs since she first discovered them in 2008.

Shoemaker's interest also started local and then expanded. A former firefighter, she was deskridden with a rotator cuff injury when she first got bit by the kit house bug. "I decided to look through Oklahoma," she says. "And I wasn't satisfied there, so I thought, I'll just look everywhere." Shoemaker checks catalog listings for customer testimonials, cross-references the names with public address records, and then looks them up on Google Earth. "It just got out of control," she says. "There were times when I was spending 10 or so hours a day doing it."

A modern-day Sears 303, next to its 1910 catalog image. The 303 is one of the rarest Sears kit homes. (Images: Rachel Shoemaker/Oklahoma Houses By Mail; Rebecca Hunter/Sears Modern Homes)

Besides cameras, field guides, and Google Earth, the biggest tool in the house-hunter's arsenal is other househunters. "The interest is gaining," says Shoemaker. "More people are becoming aware." Community members use Facebook and a large blog network as a sort of digital workshop, sharing pictures and comparing notes until they settle on a house's model and pedigree. (Judith Chabot, a St. Louis-based kit house enthusiast, has a good blog roundup.) Some have begun contributing to a nationwide master list, hoping to pinpoint exactly where all the houses are, and to enable further study. There are currently 4,400 entries—which, if Mutch's estimate is correct, leaves about 48,000 to go.

As for that unassuming Fort Wayne bungalow, it was indeed a Sears house—an Osborn, to be exact. The caravan of experts showed the homeowner the model in Houses By Mail, answered her questions, and continued on down the block. Another Sears house discovered and, perhaps, another enthusiast brought into the fold.

Update, 6/3: Houses By Mail was first published in 1986, not 1996. Thanks to David Franks for the correction, and we regret the error.