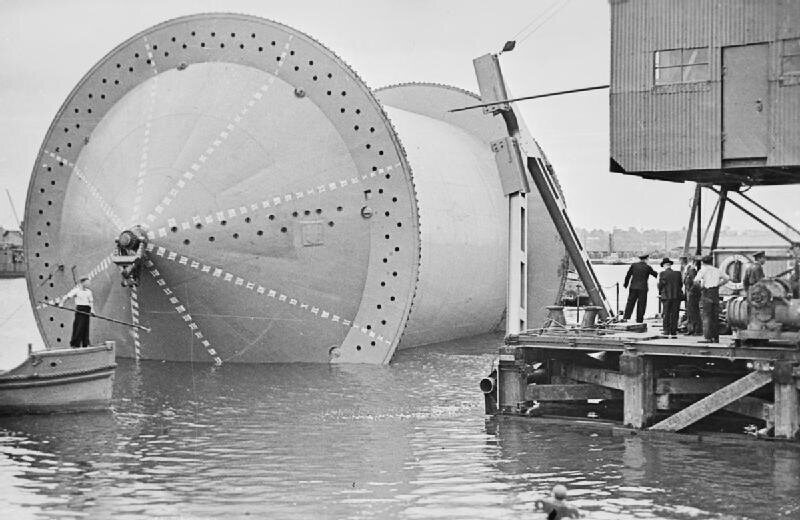

Pipelines loaded onto a 'Conundrum' during Operation PLUTO. (Photo: Public Domain)

With a view onto a wide, sandy beach and the English Channel beyond, the three whitewashed holiday bungalows along the Kentish coastline were a vision of the perfect summer escape.

Yet these charming cottages concealed a secret that would help the Allies defeat the Nazis during WWII.

Inside them were no fishing nets, deck chairs or half-empty bottles of tanning oil. Instead, the buildings hid machinery to pump thousands of tons of fuel to France, underwater. They were part of Operation PLUTO, a top-secret, and in its day, radical plan to lay pipelines across the English Channel.

Three locations along the English coastline—Sandown on the Isle of Wight, Romney Marsh and Dungeness—pumped fuel to the underwater pipelines. The stations were hidden inside the holiday cottages, a Brown's ice cream shop, and an amusement park.

PLUTO laid down 500 miles of pipelines, underwater and above land. (Photo: Public Domain)

The rationale for such a risky, technically complex project was that tankers full of petrol and oil were easy targets for German bombers, the coastline was riddled with underwater mines, and sending hefty ships to fuel Allied forces after their planned invasion of occupied France would bring more traffic to an already cluttered shoreline.

Avoiding German detection of the underwater pipeline was essential. Although there were many moving parts, the British government managed to keep the project hidden from the Nazis for nearly the entirety of the war. This was done in a few novel and very British ways.

Anyone who transported materials to the various PLUTO facilities asked for "Captain Jones" before they could continue. The British Army even commissioned an architect to construct a three-mile-long fake dock at the English ferry port of Dover, just across the Channel from the French port of Calais. It was the final act of trickery to encourage the German Army to think the D-Day invasion would take place at Calais, not Normandy.

To distract Nazis from the real target, even King George VI inspected the dock, which was replete with false pipelines, storage tanks, a fire brigade and anti-aircraft guns.

Pumping facilities hidden in cottages like this one. (Photo: Public Domain)

The first person to float the idea of an underwater fuel route was Lord Mountbatten, a senior figure in the British Army. In 1942, Mountbatten instructed the Petroleum Warfare Department to explore laying a pipeline along the English Channel. It wasn't thought possible, though; nothing like this had been tried in the theater of war before, the Channel had exceptionally strong currents and the German Army had fortified the coastline with mines and other underwater obstacles. Petroleum Warfare didn't take the matter any further.

However, Clifford Hartley, chief engineer at the Anglo-Iranian oil company, was convinced the plan could work. He was also inspired by an Iranian-designed pipe that could transport liquid petroleum at high speed. Across the Atlantic, Hartley saw how Shell had already developed technology to transport oil and other liquids across huge distances in the U.S.

The British, too, had started to lay overland pipelines across the country. Still, in the realm of pipeline innovation, the operation was virgin territory.

The British Army tested Hartley's lead pipeline—just three inches in diameter— and found out it was strong enough to resist a bomb explosion underwater. Bernard Elis led British engineers from the Burmah Oil Company in the design of a second pipeline, this time made of steel. PLUTO—Pipeline Under the Ocean—was born.

Once engineers began production, the next challenge was how to move the miles of pipeline and secure it under the Channel. To accomplish this, the Hartley pipeline was transported to one of several loading docks, then slowly coiled around 50-foot oil drums and loaded onto tankers, which would release it underwater.

Elis' steel designs, although cheaper to produce, were too fragile to be wound up in the same fashion, directly onto a boat. The material would snap. So the Petroleum Department worked with the Miscellaneous Weapons Department, nicknamed "wheezers and dodgers," to create something unique to the operation: a giant, floating spool known as "Conundrum." One of these stored up to 90 miles of pipeline. A tugboat towed the huge spool, which would spin and release the pipeline into the water.

PLUTO pipelines still around today. (Photo: CC BY: SA 2.0)

As D-Day approached, officials worked on the logistics for PLUTO. The pipelines would pump fuel across two secret routes. The first, with a code-name of BAMBI, went from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg, France, a distance of 70 miles. The other, code-named DUMBO, connected Dungeness, a small town on the south coast of England, to Boulogne, France, a distance of 30 miles.

In total, 500 miles of pipeline connected the French coast across the Channel to England, and along overland pipeline to oil terminals near Liverpool.

Some 200,000 men and 20,000 vehicles landed on the beaches of Normandy on June 6, 1944. After the successful D-Day landings, it was PLUTO's job to send fuel to support the Allied advance across France. The tankers and "Conundrums" were sent out to lay the pipeline but the first few attempts failed, which threatened the entire operation.

Those in charge decided to use the BAMBI route to Cherbourg. A stray ship's anchor broke the first lines. A propellor from a nearby ship destroyed the second attempt. After four months the first gallons of fuel rushed through the pipelines. But it was a false start. Later, more of the pipelines simply broke, and barnacles rotted the material.

Steel pipeline coiled round a giant 'Condundrum'. (Photo: Public Domain)

The army turned to the DUMBO route as its last hope. By October 26, 1944, the second set of pipelines to Boulogne was deemed a success. In a few months time, pipelines were transporting 3,000 tons of fuel a day. By the end of the war that had increased to 4,500. An estimated 172 million gallons of fuel were supplied during the landings–all underwater and under the Nazis noses.

Reflecting on the war, Dwight Eisenhower, in charge of the United States Army at the time, said that without the pipelines the U.S. forces would have run out of fuel. Winston Churchill, then British Prime Minister, declared “Operation PLUTO is a wholly British achievement and a piece of amphibious engineering skills of which we may be proud.”

The team behind PLUTO disbanded on August 31, 1945. But the holiday cottages are still around today, as are some of the overland pipelines.