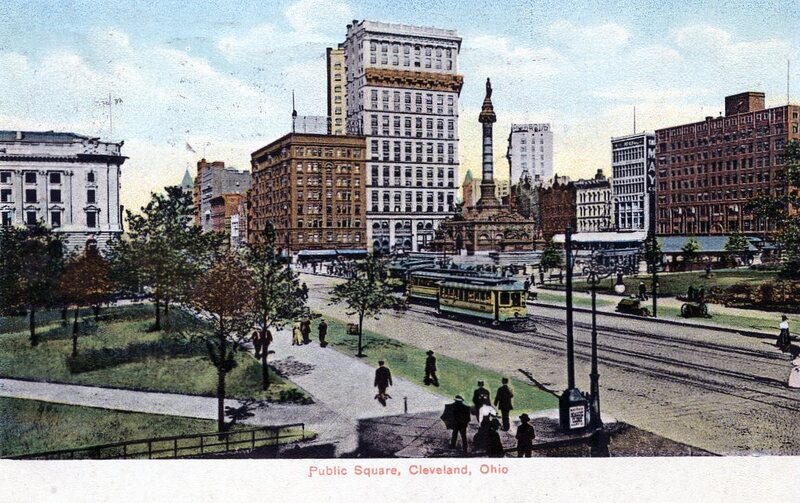

Cleveland's Public Square in the 1910s. (Photo: Public domain)

If you look at a map of Connecticut, paying particular attention to town names, and then do the same to Northeast Ohio, you might get the impression that, at some point, the map was folded over onto itself before Ohio had been filled in, and before the ink of Connecticut’s place names had dried.

That’s because in a sense, it was. In America’s early years, what is now Northeast Ohio belonged to Connecticut, and in the late 1700s and early 1800s, Connecticut transplants gave Ohio many of its names, institutions, traditions, and people, into what was then called the Connecticut Western Reserve.

That legacy remains apparent to this day, not just in place names—there are, among dozens of examples, Kents, Saybrooks, and New Londons in both states—but in architecture, city planning, and even the quality of the area’s higher education. Cleveland’s famous Public Square, for example, recently refurbished for the Republican National Convention? They can thank a guy from Connecticut for that. Ditto for pretty much every other town square in this part of the state, in addition to Case Western Reserve University, Oberlin College, and a church in Tallmadge, Ohio that Life magazine once used as an avatar of New England.

Residents of the Nutmeg State, in other words, will find a lot that's familiar in Cleveland and its suburbs. And to the men and women two centuries ago who battled mosquitoes, disease, thick woods, and death to settle the Western Reserve, that's no accident.

Connecticut’s history with Ohio began early. Very early. King Charles II’s royal charter of 1662 legitimized the colony’s political existence and established its borders: To the east, “Narraganset-Bay;” to the north, “the Line of the Massachusetts-Plantation;” to the south, “the Sea;” and to the west, “the South Sea” - i.e., the Pacific Ocean. If Connecticut had retained this territory, it would now encompass not just part of Ohio but also Chicago, Omaha, Salt Lake City, and the northernmost sliver of California.

After the Revolutionary War, Connecticut, like other states, ceded most of its Western land to the new United States. But it refused to part with a roughly rectangular piece of what is now Northeast Ohio and which was, then, referred to as New Connecticut, or the Connecticut Western Reserve. Even so, over a decade after the war ended Connecticut did part with much of the land, selling over three million acres of it for $1,200,000 to a group of investors called the Connecticut Land Company. The westernmost 500,000 acres had previously, in 1792, been designated as compensation for Connecticut residents who had lost property in British raids, otherwise referred to as the Sufferers’ Lands or the Firelands.

Surveyors in the ensuing years explored, measured, mapped, and divided the land into neat sections. And pioneers from Connecticut and other Eastern states trickled in westward to settle it, eventually forming the basis for what we have today: an urban mass of over four million, populated by residents who are fiercely loyal to their little sliver of America.

A marker in Conneaut, Ohio. (All photos by Johnna Kaplan except where noted.)

Recently, I took a trip there myself in part to compare its present with the east-coast roots of its past, beginning in Conneaut, just over the Pennsylvania-Ohio line, where a sign proclaiming “Life's just better here!” echoed the promotional materials Connecticut speculators used to entice pioneers in decades past.

On Conneaut’s humble Main Street, a brown-and-gold Ohio historical marker commemorates the arrival, on July 4, 1796, of the first Connecticut Land Company surveying party. The group, led by General Moses Cleaveland, landed at the mouth of Conneaut Creek. They “gave three cheers and christened the place Port Independence,” Cleaveland wrote in his journal, parts of which are kept at the Western Reserve Historical Society. “We drank several toasts, viz., 1st. The President of the United States. 2nd. The State of New Connecticut. 3rd. The Connecticut Land Company. 4th. May the Port of Independence and the fifty sons and daughters who have entered it this day be successful and prosperous. 5th. May these sons and daughters multiply in sixteen years sixteen times fifty. 6th. May every person have his bowsprit trimmed and ready to enter every port that opens.” They “closed with three cheers,” Cleaveland recorded, then “drank several pails of grog, supped and retired in remarkable good order.”

Further along the lakefront, meanwhile, familiar place names began to emerge: Saybrook Township and New London Road, among others. And, while I was in a car, early “emigrants,” as they were called, traveled by wagon or oxcart or on foot, carrying across the Alleghenies their household goods and the names of the places they were leaving: New Haven, Trumbull, Danbury, Fairfield, Ridgefield, Groton. Even so, not all Reserve towns were named for Connecticut places. Euclid was named for the Ancient Greek mathematician, an homage to the Connecticut surveyors who measured the township and then purchased it for themselves. Warren, Kent, Tallmadge, and many others were named for Connecticut investors, settlers, or landowners. Cleveland was, of course, named for Moses Cleaveland; the extraneous “a” was later abandoned. One story behind the change has it that the Cleveland Advertiser found they couldn’t fit the longer spelling in a headline when they began publishing in January 1831.

Charter Oak Park in Painesville, which features a statue of General Edward Paine.

The city of Painesville, meanwhile, was named for its founder General Edward Paine, a Bolton, Connecticut native who fought in the Revolution and went on to serve in Ohio’s Legislature. His statue, looking stern in military uniform, stands in a small park named for Connecticut’s now-dead famous Charter Oak tree. That tree, located in Hartford, was felled in 1856, but was said to be where colonists stashed their royal charter – the very document that had granted them rights to the future Western Reserve in the first place—after King James II revoked it in 1687. And here, hundreds of miles away, was one of the tree’s direct descendants.

Nearby, I found another Connecticut transplant: a quintessential New England town green. Greens, or “squares” in Ohio, were part of the plan from the beginning, even before the townships were being measured out by teams of surveyors, the first in a stream of settlers who tried, and sometimes failed, to tame the land.

The first surveyors, for example, ran into a host of problems: they often lacked food and water, ate wild berries and rattlesnakes, struggled through swamps, and endured “Musketoes & Gnats,” one of them reported. That witness, an astronomer named Seth Pease recorded the grim tally on his travels there in 1796 and 1797. There were injuries—“John Dorn put his wrist out of joint”—but, also, deaths: “David Eldride…was unfortunately drowned…Mr. Hart used every precaution to Recover him but to no purpose they brought the Corpse to the Cuyahoga River.” He chronicled illnesses like “dysintery” and fits of “Ague & Fever,” and their treatments - bark, Tartar Emetic, and “Reubarb.” He also described encounters with Indian “friends,” in which the flow of whiskey both smoothed and helped exacerbate any undercurrent of misunderstanding.

The land was measured using chains, compasses, and the stars. It was numbered in ranges from east to west, and in towns from south to north. And even today, data about northeastern Ohio municipalities sometimes includes their place on this grid. Tallmadge, Ohio, was once known as Town 2, Range 10, for instance, and while elsewhere in the state, townships are six miles square, in the Western Reserve, because of the surveyors’ legacy, they are five.

The First Congregational Church in Tallmadge, Ohio.

The town squares of Northeast Ohio were particularly evocative of Connecticut. Painesville’s featured an impressive copper-domed city hall. Chardon’s topped that with the High Victorian Italianate Geauga County Courthouse, which looked like a fancy cake. Tallmadge’s square was a circle. On it stood the First Congregational Church, the oldest church building in Ohio in continuous use as a place of worship, which looked so New England-y that in 1944, Life put it on their cover to illustrate a Thanksgiving story about “the devout spirit of New England Puritans.”

All of this sprung from conditions that were, initially, bleak. Joseph Badger’s 1802 account, for example, was typical. Sent west by the Connecticut Missionary Society to spread New England Congregationalism among both Indians and white settlers, Badger, his, wife, and their six children “loaded our wagon, drawn by four horses, with as much household furniture as we could stow together.” They “made [their] way, slowly, cutting…many small trees and saplings to make room for the wagon.” On the “miserable road in the Connecticut Western Reserve,” they “passed…more than two hundred miles through a wilderness, with but here and there a log cabin.” When they reached their lot, Badger built his own cabin, “a rough one, round logs, without a chink; and only floored half over…and partly roofed…with no chimney.”

And once a family had a home, they had to procure necessary goods from more settled areas elsewhere, traveling by boat on fickle Lake Erie or by horse or wagon through untamed woods.

The chapel on the campus of Western Reserve Academy in Hudson, Ohio, which was originally the home of what is now Case Western Reserve University.

Badger tried to make the best of it, while some others, like the caustic Margaret Dwight, a niece of Yale University president Timothy Dwight, did not. Margaret Dwight snarked her way through an 1810 trip to the Reserve in a letter to a friend. Dwight looked down on the family she traveled with (“I will never go to New Connecticut with a Deacon again, for we put up at every byeplace in the country to save expense – It is very grating to my pride to go into a tavern & furnish & cook my own provision – to ride in a wagon &c &c”) as well as the people she encountered along the way (“I should not have thought it possible to pass a Sabbath in our country among such a dissolute vicious set of wretches as we are now among – I believe at least 50 dutchmen have been here to day to smoke, drink, swear…laugh & talk dutch & stare at us…It is dreadful to see so many people that you cannot speak to or understand.”) Her tavern reviews were scathing (“the pillow case had been on 5 or 6 years I reckon”) and her put-downs caustic (“I found the people belong’d to a very ancient & noble family – they were first & second cousins to his Satanic Majesty.”)

Other settlers more quietly went about the business of building, essentially, a new civilization. Sixteen years after Dwight’s passage, Connecticut natives established the Western Reserve College and Preparatory School as a sort of frontier Yale, laying the seeds for what is now Case Western University. Its original campus is now the prestigious boarding school Western Reserve Academy. And Owen Brown, the father of abolitionist John Brown, helped found the groundbreaking Oberlin Collegiate Institute, now Oberlin College. (John Brown, who at one point operated a tannery in Kent on a site that is now preserved as a public park, was just five years old when his family moved. He found his new home “a wilderness filled with wild beasts, & Indians.”)

In addition to schools, there are also libraries, like one in the Cleveland suburb North Olmsted, named for the Connecticut sea captain Aaron Olmsted. In return for the naming, Olmsted’s family sent the town 500 volumes, forming the basis of the Oxcart Library, the first public library in the Western Reserve. Today, 159 of the books can be seen in a glass case in the North Olmsted branch of the Cuyahoga County Public Library, where the books live on in an area roped off like a VIP section.

A replica of the cabin of Lorenzo Carter, an early settler, in Cleveland.

All of this development came at a steep price to the area’s native populations, who were pushed out with little recompense. American Indians’ claims to most of the land were extinguished by the 1795 Treaty of Greenville, which came after a bitter defeat in the Northwest Indian War at the hands of American soldiers. Moses Cleaveland bought off a handful other claims with, to quote Seth Pease, “D.500. New York courency, in Goods” plus “2 Beef Cattle and 100 Gall of Whisky.” And later U.S. administrations would force American Indians farther and farther west.

African-Americans, meanwhile, didn’t get a much better deal. That’s because while the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 forbid slavery in the Territory, local “Black Laws”—which required any black residents to prove their freedom—kept most African-Americans out.

For the white settlers, though, development continued full steam ahead. Cleaveland laid out his eponymous city himself, starting with a public square. He boldly predicted that because of its prime location, Cleveland might soon grow to be “as large as Old Windham” in Connecticut, which at the time had 2,700 residents. (Cleveland now has a population of over 390,000.)

Farther to the west I found the towns that had been settled by the so-called Firelanders, whose property had been destroyed by the British during the Revolutionary War. Farther inland, the place names were familiar but the rural landscape did not match up with the rolling hills, winding roads, and stone walls characteristic of New England’s agricultural areas. Here there was just open space, bisected by carefully-planned roads that met at right angles.

And it was on one of these roads, before I left, that I drove to the western edge of the Western Reserve. There, in rural Huron County, on a patch of tall grass between two country roads, a small brown marker stood beneath an advertisement for log home logs. It read: ENTERING THE FIRELANDS ESTABLISHED 1792.

I circled the sign a few times. Then I headed back towards New London, Connecticut, where, occasionally, people still talk about which buildings survived the Revolutionary War, as well as those that were lost.