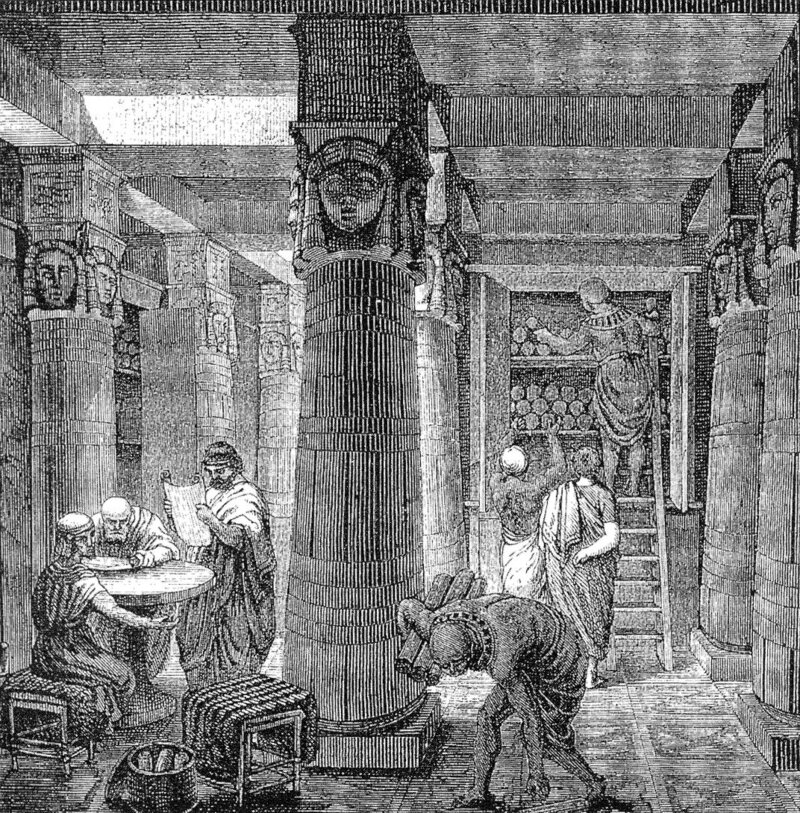

An artistic interpretation of the Library of Alexandria based on archaeological evidence by O. Von Corven. (Photo: Public Domain)

In the Hellenistic Era—that's 323 BC to 31 BC, for all you numbers fans—the Library of Alexandria, Egypt was a research hub of high prestige. But while certainly the largest of its time and the most famous, the Library of Alexandria wasn’t the only institution of its kind. Libraries throughout the ancient world competed to be the best Greek library, in rivalries that proved as dangerous and unscrupulous as actual wars.

Perhaps the most vicious rivalry of all was between the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum in the city of Pergamon—present-day Bergama, Turkey. In this conflict, the ego-driven kings of both cities enforced various sneaky maneuvers to stunt the growth of the opposing collections.

“The library was a means [for the kings] to show off their wealth, their power, and mostly to show that they were the rightful heirs of Alexander the Great,” says Gaëlle Coqueugniot, an ancient history research associate at the University of Exeter.

When Alexander the Great died in 323 BC, his empire stretching from Macedon to the western border of India was divided into three dynasties: Antigonids, Seleucids, and Ptolemies. All of the kings of Macedonia competed to become the commander’s rightful successor. The struggle for royal supremacy spilled into scholarship and preservation of Greek culture, giving way to a new wave of elaborate libraries.

Rulers grew their cities to prove that they were the rightful heir of Alexander the Great. (Photo: Berthold Werner/CC BY-SA 3.0)

The libraries that existed previously in Mesopotamia and in Egypt were primarily personal collections or kept in temples. In the third and second centuries BC, there was a boom in the number of institutions that kept books.

The Library of Alexandria, which ultimately consisted of approximately 500,000 scrolls and boasted early texts by Euripides, Sophocles, and Homer, was first conceptualized by King Ptolemy I. The Ptolemaic dynasty was able to spend big on the institution thanks to the riches of Egypt’s fertile land and resources from the Nile, including papyrus, the ancient world’s main writing material. As a result, the library had an edge in development over others. The Ptolemaic kings were determined to collect any and all books that existed—from the epics, tragedies, to cookbooks.

“The Ptolemies aimed to make the collection a comprehensive repository of Greek writings as well as a tool for research,” wrote former classics professor at New York University, Lionel Casson inLibraries of the Ancient World. To obtain this comprehensive collection, “the Ptolemies’ solution was money and royal highhandedness.”

A bust of a Ptolemaic king, most likely Ptolemy II Philadelphus. [Photo: Marie-Lan Nguyen/CC BY 2.0]

During the Ptolemaic hunt for centuries-old books from Greece, it’s said that a new industry emerged of forging ancient books to look more antique, thereby increasing the rarity and value. While the evidence of such a forgery trade is difficult to determine, Coqueugniot finds it probable since the kings were so bent on having the most prestigious texts in their library.

“Of course the Library of Alexandria was probably the largest one, but out of all the other kings that tried to be in competition with the Ptolemaic kings, Pergamon was the closest,” says Coqueugniot. It contained about 200,000 scrolls.

An illustration of the acropolis at Pergamum. (Photo: Wellcome Images/CC BY 4.0)

The Library of Pergamum wasn’t built until a century after the Library of Alexandria. Pergamon was originally part of the Kingdom of Antioch, but when it gained its independence in the late third century BC, the monarch wanted to be among the elite international powers. To better support Greek culture, the city started building the library. There’s a legend, wrote Casson, that citizens who moved to the growing acropolis and happened to own some of Aristotle’s prized collection buried the books in a trench to keep them hidden from royal officials. King Eumenes II finished the library of Pergamum, eagerly trying to catch up to Alexandria’s in size and quality.

“If we can believe tales that went the rounds in later centuries, the Ptolemies were not at all pleased by the challenge on the part of an upstart dynasty to the preeminence of their famed institution,” wrote Casson.

They were competing for the same books, the same parchments, and even the scholars’ of the two institutions had conflicting interpretations and edits of texts, says Coqueugniot.

“The Library of Pergamum managed to attract some scholars on editing and commenting on Homer—the Iliad and the Odyssey—which was exactly the main specialty of the main Library of Alexandria,” she says. Since Homer’s poems were meant to be read aloud, there are several written versions. Both libraries tried to obtain all of them, comparing which were the oldest and most genuine.

A fragment of Homer's Iliad on papyrus. (Photo: Public Domain)

Much like how athletes are drafted to rival teams in today’s sports, libraries “attracted scholars by offering one better wages than the other kings,” she says. The rivalry “probably stimulated the production of the scholars in both centers, but it was also quite unhealthy meaning that some scholars we know were imprisoned so they couldn’t leave to the other part of the world.”

It’s said that Ptolemy V threw Aristophanes of Byzantium, a grammarian and critic, into prison after hearing rumors that he may leave Alexandria to join the academics in Pergamum, wrote Casson.

One of the Ptolemies’ most drastic schemes to strike down the Library of Pergamum was the sudden cut of its trade of papyrus with the city of Pergamon. The Ptolemies hoped that if the main component of books was limited and hard to obtain, it would prevent the Library of Pergamum’s collection from growing. However, Pergamon came up with an alternative. Roman writer and scholar Marcus Terrentius Varro documented the event: “the rivalry about libraries between king Ptolemy and king Eumenes, Ptolemy stopped the export of papyrus … and so the Pergamenes invented parchment.”

Papyrus plant, Egypt banned trade with the city of Pergamon. (Photo: mauroguanandi/CC BY 2.0)

While it’s not possible for Pergamon to have invented parchment since scriptures on stretched leather have been found earlier in the east, the lack of papyrus may have pushed the king to expand the use and development of leather as a writing material, Coqueugniot says. The word for parchment in Latin, “pergamīnum” literally translates to “the sheets of Pergamum,” she says.

Even though the rivalry between the great libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum may have made the world of academia messy and political, the effort poured into the institutions’ development changed the state of scholarship and preservation. Without the feud for royal power and respect for Greek culture and academics, libraries may have never gotten the attention they needed.