In 1826 in a southern suburb of Cape Town, South Africa, a frail-looking doctor with red hair prepped his instruments for a highly dangerous procedure—a cesarean operation. Once Dr. James Barry, a Royal British Army surgeon who was no taller than five feet, had assessed the severity of the patient’s contractions, he saw there was no other choice. The newborn needed to be removed surgically.

Barry had read of only three cases where both the mother and the child survived. None of them were performed in the British Empire. But Barry had a unique perspective to most doctors of the time.

“Aside from his expertise in midwifery, he had a secret advantage,” writes Michael du Preez and Jeremy Dronfield, experts who have written extensively about Barry’s life. “There was not another practicing physician or surgeon in the world [in the 19th century] who knew from personal experience what it was like to bear a child.”

Barry became the first doctor in the British Empire to perform a successful cesarean operation. It was one of many major medical contributions the Irish surgeon accomplished for the British military, from enforcing stricter standards for hygiene, improving the diet of sick patients, to popularizing a plant-based treatment for syphilis and gonorrhea. Barry served around the globe, eventually earning the title of Inspector General, the second most senior medical position in the British Army.

But despite these achievements, Barry’s reputation was kept a secret for nearly a hundred years. The military locked away the doctor's records after finding out Britain’s Inspector General was born a woman.

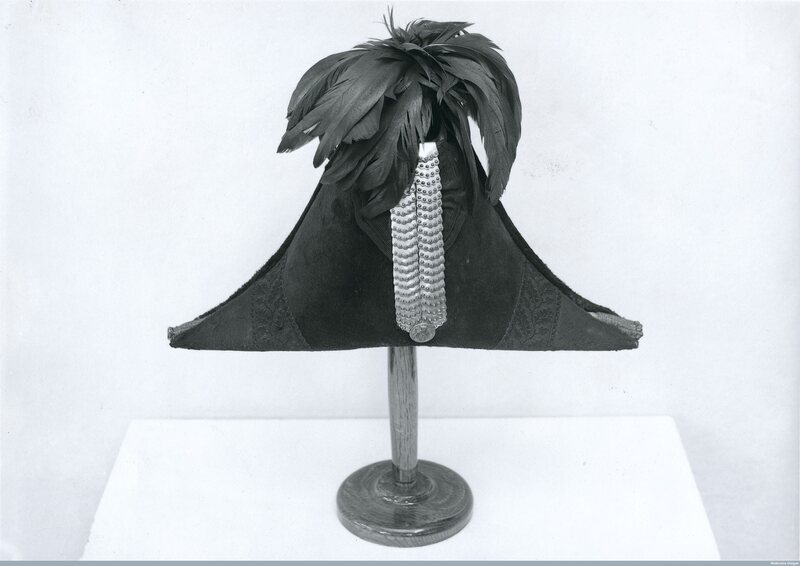

Around the age of 20, Margaret Ann Bulkley became James Barry: a hot-tempered ladies’ man donning three-inch heeled shoes, a plumed hat, and sword. In 1809, she decided to embody a smooth-faced young man in order to attend the men's-only University of Edinburgh and practice medicine—a guise that would last for 56 years. It wasn’t until after Barry’s death in 1865, that the doctor's secret was finally discovered.

Bulkley’s masquerade was “one of the longest deceptions of gender identity ever recorded,” du Preez writes in The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. “Dr. Barry is remembered for this sensational fact rather than for the real contributions that she made to improve the health and the lot of the British soldier as well as civilians.”

Born in 1789 in Merchant’s Quay, Cork, Ireland to a grocer father, Margaret Ann Bulkley was a sociable and outgoing child. As a young girl, she once wrote of her desire for “a sword and a pair of colours [military uniform].”

Bulkley had an older brother, John, whose “fecklessness and selfishness brought the family in debt,” writes du Preez in the South African Medical Journal. John received most of the family’s money to fund his education and an apprenticeship at an attorney’s office in Dublin. In 1803, he became infatuated with an upper-class woman and spent £1,500 of the family’s savings on the marriage settlement. The Bulkley family spiraled into bankruptcy, and Margaret's father was sent to prison when she was 14, leaving the family without a source of income.

Her mother sought the help of her older brother in London, the famed Irish artist James Barry. The artist had a difficult personality, however, and was not welcoming to his sister's family when they arrived in London. Yet Barry introduced Margaret to his elite circle of friends, some of whom offered her teaching and mentorship. Margaret did not have the social standing to marry well, but her family hoped she could study to become a teacher or governess.

While mentoring his new charge, the Venezuelan general and revolutionary Francisco Miranda became impressed by Bulkley's intelligence. He was the first friend of Barry's to encourage Bulkley to take on the persona of a man to enter the male-dominated field of medicine. After Margaret graduated from medical school, he reasoned, Bulkley could shed this disguise and practice freely as a woman doctor in Venezuela. Miranda proposed she use her medical skills in his revolutionary efforts in Caracas, Venezuela.

“In the early 19th century, only men were admitted to the medical schools in Britain, and discovery of the sex of the young medical student would have ruined any chance of success,” writes du Preez.

In 1806, her uncle James Barry passed away and left his fortune to the family. In turn, Bulkley assumed Barry’s name and used the money to finance three years of medical studies at the University of Edinburgh beginning in December 1809.

The new James Barry was a diligent student. Barry pursued a diverse load of coursework, ranging from anatomy and surgery, botany, and midwifery. The number of subjects Barry studied was only exceeded by one Army medical officer and matched by one other student in his cohort of over 45 doctors, wrote du Preez.

In 1812, Barry was nearly exposed on the cusp of graduating. Edinburgh authorities tried to bar Barry from taking the four-stage final exams, claiming that the student looked underage but likely suspecting more. Yet at the time it was not unusual to see 16-year-olds at medical schools, and the ban was not enforced. After completing a thesis on the femoral hernia (primarily a female condition), Barry became the first woman to graduate from a medical school in Britain.

Unfortunately, Barry's post-graduation plans with Miranda would never come to fruition. In the summer of 1812, Miranda’s revolution was thwarted and he was imprisoned by the Spanish. But instead of coming out as a woman in Britain instead of Venezuela, Bulkley opted to continue the role of Dr. Barry—hiding under the false identity till death.

Barry joined the British Army's medical unit in 1813. It’s unknown how the young doctor passed the mandatory physical exams, but scholars believe Lord Buchan, a nobleman who had been a friend and supporter of her late uncle, likely played a role. In 1815, Barry was appointed as colonial medical inspector in Cape Colony, South Africa, and was granted authority over all medical, surgical, and public health matters in the colony.

People noted Barry's unusual lifestyle. The medical inspector was a vegetarian, kept a goat nearby to drink its milk, carried a small dog named Psyche, and was almost always seen with a trusted servant, Danzer, who would stay by Barry's side for 50 years. Each morning, Danzer laid out six small towels for Barry to wrap and conceal his curves and broaden his shoulders. The doctor wore high-heeled boots, and “the longest sword and spurs he could obtain,” surgeon Edward Bradford wrote when he met Barry in Jamaica in 1834.

Barry's flirtations with women also threw off suspicion. Many women fell for Barry’s sweet, beardless face—a latter-day Orpheus, according to du Preez and Dronfield. Women stated how Barry was a “perfect dancer who won his way to many a heart,” while comrades often saw the doctor attached “to the finest and best-looking woman in the room."

Barry, who cursed constantly and had a fastidious temperament, often butted heads with other doctors when their treatments conflicted, and even fought a couple of duels with rival officers. The hot-headed doctor even got into a tussle with the medical reformer and nurse Florence Nightingale, who wrote, “he behaved like a brute” and was “the most hardened creature I ever met throughout the army.”

Despite having a bad temper, Barry had a comforting bedside manner. During the cesarean delivery in Cape Town, Barry stayed next to the mother’s side for the rest of the day. The couple, Wilhelmina and Thomas Munnik, named the child James Barry Munnik and Barry the godfather. In gratitude, Barry offered what is now one of the most famous portraits of him—a small painting of the doctor in a red uniform coat.

Barry was reserved with most people, but had a close relationship with Lord Charles Somerset, Cape Town’s governor. Lord Charles favored Barry, providing the doctor with private chambers. When Lord Charles was on his deathbed, Barry clashed with the prestigious physician caring for him. People spread rumors that the governor and doctor were in an intimate relationship, but the scandal was never proven. Scholars believe that Lord Charles likely knew Barry’s true identity, and some claim he may have loved the doctor.

Barry wrote in a diary that Lord Charles was, “my more than father, my almost only friend.”

In 1857, Barry fell ill while stationed in Canada and was taken back to London. The doctor and surgeon died at age 76 on July 25, 1865, most likely of dysentery or cholera. Barry's medical career had lasted 46 years, with the celebrated doctor assisting the wounded in the Peninsular War, at a military hospital at Plymouth, and treating French prisoners from Waterloo, in addition to stints in South Africa and Canada, writes du Preez in the Bulletin of the Royal College of Surgeons of England.

It was Barry's final wish to remain in his original clothing and buried immediately, explains Earl Nation in the Journal Urology. However, Barry's servant Sophia Bishop examined her boss's body and discovered the doctor was “a perfect female,” with stretch marks indicating the birth of a child.

According to du Preez and Dronfield, Barry had a daughter back in Ireland, Juliana Bulkley, who never knew that her mother was an accomplished Army doctor practicing medicine around the world. It remains unclear who the girl's father was, but scholars suspect it could have been one of Bulkley's relatives.

Military officials soon found out of Barry's great disguise, and that they had unknowingly employed a woman for nearly half a century. Ashamed of these revelations, top officials in the Army tried to cover it up, imposing a 100-year embargo on all documentation concerning the "fraudulent" Inspector General.

Barry had already been given a military funeral at Kensal Green Cemetery in London, but after the revelations only a plain sandstone marker was placed atop the grave. The death certificate was male, and there was no obituary in the papers for the well-known doctor.

The tale was not unknown to the contemporary public; over the next few years, there were news stories, novels, and a play that sensationalized Barry’s life and legacy. But slowly, the military’s efforts to obscure the doctor's career sunk in, and Margaret Ann Bulkley and Dr. James Barry’s existence disappeared.

The doctor’s story was finally unearthed in 1958 by scholar Isobel Rae, who discovered the “Barry Papers” in the British War Office and Public Records Archives. She wrote the first researched biography of Barry and Bulkley, which was followed by articles, books, and a film. On December 13, it was announced that actress Rachel Weisz will play Bulkley and Dr. Barry in a future biopic.

Margaret Ann Bulkley found a means to pursue her ambitions despite the gender restrictions of 19th century society. The globe-trotting doctor worked to advance the field of medicine half a century before Elizabeth Garrett became the first known female to qualify as a doctor in Britain, in 1865—the same year Barry died.

While Dr. James Barry was “pernickety, bad-tempered, frail, fastidious,” one acquaintance recalled, “this small, curious person raised the standards of medicine and touched the public conscience about the condition of the most degraded members of society...wherever she went.”