Warner Lew claims he has witnessed two people moan with rapture while eating smoked shad. Not just two people—two teenagers. They happened to have stopped by Lew’s kitchen right as he was taking a batch of canned shad out of the pressure cooker, and they were willing to give it a try. “I wish I had recorded the sound,” says Lew. “I have not seen people moan with rapture many times. How many people moan with rapture over fish?”

Smoking and canning shad, a bony fish that once filled rivers in Pennsylvania and Maryland, was an experiment for Lew, a fisheries biologist and fleet manager based in Seattle. When a fisherman friend had mentioned that he had about 40 pounds of shad chilling in his freezer, Lew knew what to do with it. He would smoke it and can it. He had created award-winning canned herring using this strategy, and he was convinced that the same technique would melt the shad’s bones and make the fish irresistible. Moan-inducing, even.

That first batch was such a success that Lew is now racing to sell canned shad to the masses. “We just have to get people to fall in love it,” he says. “Everyone will be eating shad instead of bacon for breakfast.”

Shad may be a rare treat these days, but it was once as ubiquitous on American menus as chicken is now. The fish served as a key food source for early colonists, so much so that Connecticut and Pennsylvania once started an armed conflict over a particularly abundant shad territory. Like salmon, shad live in the sea but swim upriver to spawn. Over time, river dams on the U.S. East Coast eventually shrank their numbers in that part of the country, by making it harder for the fish to reproduce.

On the West Coast, the fish’s fate is reversed. There are abundant shad in the Columbia River today, which runs along the border of Oregon and Washington. At the request of California fish commissioners, shad were brought to the Pacific Ocean by Seth Green, a New Yorker who pioneered fish farming. In 1871, Green packed 12,000 young shad into four 8-gallon milk cans and loaded them on a train; a week later, the fish arrived in California with their numbers only down a couple thousand. The shad thrived in their new home; by 1880 they had discovered the Columbia river, and in 1885 young shad were purposefully seeded in the river. Now, millions of shad regularly run up the Columbia River each season, far outnumbering salmon.

But in the Pacific Northwest, shad are treated like a trash fish, rarely harvested on purpose and usually turned into fish meal or cat food when they show up as bycatch. If fishermen use gillnets to catch shad, they often snag salmon as bycatch. In the Pacific Northwest, salmon fishing is closely regulated, and any salmon that show up in shad nets count against a fisherman's salmon numbers for the year. Commercial fishermen generally prefer to go after salmon on purpose. “No one wants the shad,” says Marty Kuller, the fisherman who provided Lew with 40 pounds of frozen fish. “The shad fishery has gone to the wayside.”

Lew believes that could and should change. “I’ve eaten smoked shad, and I think it’s phenomenally good,” he says. “If it was mediocre, I wouldn’t be as excited about it. But I think it’s pretty damn good. It’s a shame we don’t eat something that good, compared to the fish we do eat. Tilapia? Give me a break. Or catfish? It’s like the tofu of the sea. It’s the vehicle for the sauce.”

He wants to be clear that he is not knocking tofu—he eats a lot of tofu, probably more than most people. The point is that shad has flavor. Though it’s a big fish and cooks up white like tilapia or catfish, it had an unusually high oil content, which is what makes fish delicious.

Lew has long been invested in convincing people to eat under-appreciated seafood. Back in the 1980s and ‘90s, he tried to gin up interest in the culinary potential of sea cucumbers, geoduck clams (an intimidatingly large species native to the Pacific Northwest), and salmon roe. Maybe it’s his parsimonious nature, he says; maybe it’s the influence of his Chinese grandmothers and a food culture in which nothing’s wasted.

His greatest success so far has been with herring, which caught his interest back when he was working as a deckhand in Bristol Bay, Alaska, where herring are caught mostly for their roe. Back in March 2011, Lew was eating sardine toast at the Walrus and the Carpenter, a Seattle restaurant, and thinking “we’ve got some fish as good as this.” He brought in a sample of three frozen herring and gave them to the kitchen. One of the restaurant’s founders, Renee Erickson (who’s since won James Beard award), is a “big fan of small fishes,” says Lew. “It was a natural fit. I started supplying her with frozen fish.”

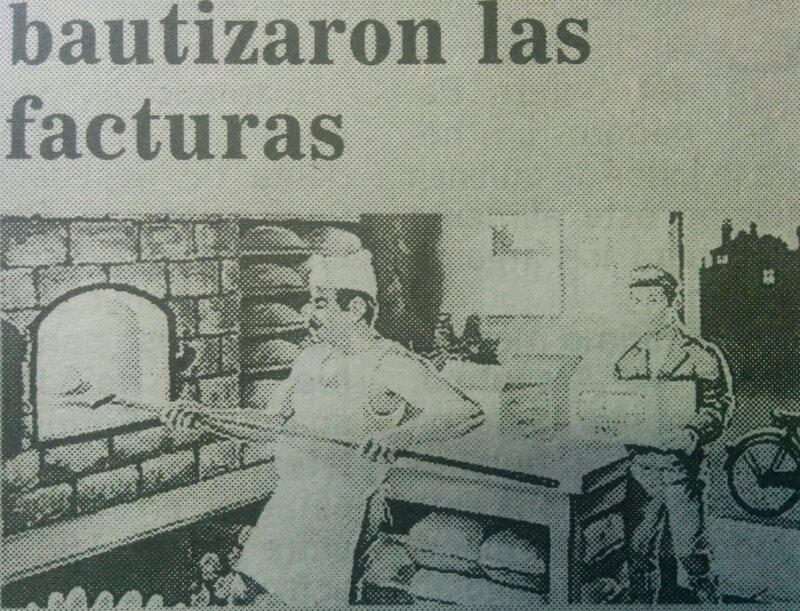

A couple years later, a skipper friend taught him how to smoke and can fish, using a technique from a village near Nome, where his mom was from. “It’s pretty simple, but there are a couple of tricks that he taught me,” says Lew. “I gave a sample to Renee, and she liked it.” Soon Lew was canning “Deckhand’s Daughter Smoked Herring,” which won a Good Food award this past February.

Lew’s shad will get essentially the same treatment as the herring. “If you just can it, it’s okay, but when you smoke it, that pushes it over the edge,” he says. If he can convince a wider audience that shad is moan-inducingly delicious, he and Kuller, the fisherman, could take advantage of the abundance of shad flooding the Columbia River each season. Oregon and Washington have started giving out experimental permits that allow commercial fisherman to catch shad with a purse seine net, which could reduce the salmon by-catch and make shad a more attractive catch for fisherman. “Warner’s interest has sparked my interest in it,” says Kuller. “There’s a resource that’s kind of untapped right now.”

“We just have to get people to fall in love with it,” says Lew.