This living church is still growing. (Photo: Alessandro/CC BY 2.0)

We usually use trees as building material in the form of struts and planks. But all over the world, people have found ways to create dwellings, bridges, and sculptures out of trees without even cutting them down. Using trees to create living structures is much slower to build (read: grow) than traditional methods, but it creates some truly fantastical natural creations. Take a look at some of the world's coolest feats of arbortecture.

1. Willow Palace

Auerstedt, Germany

(Photo: Pfauenauge/CC BY 2.0)

This amazing sylvan dome, first planted in 1998, took 10 years to grow to completion. It is now one of the most stunning examples of arbortecture in the world. The brainchild of architect Marcel Kalberer, the dome is formed by a central copse of trees the connects with a ring of trees planted around the perimeter and trained towards the center. Today the "palace" looks like the type of place a fairy congress might be held.

(Photo: Michael Sander/CC BY-SA 3.0)

(Photo: Murray Bosinsky/Public Domain)

(Photo: Pfauenauge/CC BY 2.0)

2. Tree Cathedral

Bergamo, Italy

(Photo:Alessandro/CC BY 2.0)

This Italian work in progress was planted in 2010 to realize a vision held by the late artist Giuliano Mauri. It is designed to grow into 42 living columns that will create a five-aisle basilica. The trees that are growing there now are supported by wooden frames that will fall away with time, as the trees grow. While it hasn't grown a roof yet, the arches of the future aisles are already beginning to form.

(Photo: Pava/CC BY-SA 3.0 IT)

(Photo: Alessandro/CC BY 2.0)

(Photo: Alessandro/CC BY 2.0)

3. The Green Cathedral

Almere, The Netherlands

(Photo: RogAir/CC BY-SA 3.0)

This cathedral of trees is a bit different than many of the other examples of living architecture out there in that instead of repurposing or training the trees to their specific use, the trees of the Green Cathedral have simply been planted in the shape of a church. From the ground, it would be easy to mistake the formation for nothing more than a cleanly planted grove of trees, but from the air, the form becomes more clear. Luckily for those without a helicopter, a plaque on the site explains the true nature of the living church grove.

(Photo: Stipo team/CC BY-SA 2.0)

(Photo: Stipo team/CC BY-SA 2.0)

(Photo: Stipo team/CC BY-SA 2.0)

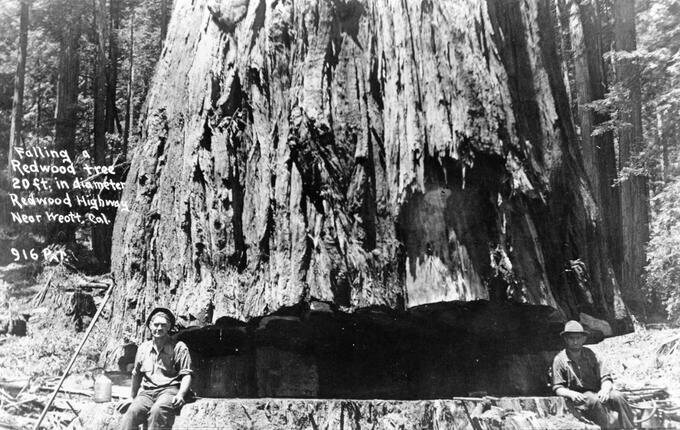

4. The Chapel Oak

Allouville-Bellefosse, France

(Photo: Marie Thérèse Hébert/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Another variety of living architecture takes a large preexisting tree and repurposes it as a useful structure. The Chapel Oak in France is just such a building. Looking like something straight out of Harry Potter, this giant tree houses two chapel spaces in its hollow interior, which was gutted by a lightning strike centuries ago. The chapels were built in the 1600s, and still exist today, accessed by a spiral staircase.

(Photo: Ji-Elle/Public Domain)

(Photo: isamiga76/CC BY 2.0)

(Photo: isamiga76/CC BY 2.0)

5. Jembatan Akar

Padang Barat, Indonesia

(Photo: ilhamsaibi/CC BY 2.0)

Root bridges are a unique form of living architecture that are exactly what they sound like. The Jembatan Akar bridge in West Sumatra has been made of the woven together roots of two banyan trees that stretch across the Batang Bayang River. it was started in 1890 by a teacher who was looking to create a way for his students to safely and easily cross the river. He first trained the roots across a bamboo support until they knit together. Ever since, the bridge has become more robust, sturdy, and incredible to behold.

(Photo: Meutia Chaerani / Indradi Soemardjan/CC BY 2.5)

6. The Root Bridges of Cherrapunji

Sillong, India

(Photo: Anselmrogers /CC BY-SA 4.0)

The real capital of the root bridge is in northeastern India, where the Ficus elastica rubber tree is common. The flexible, elastic roots of the tree provide the perfect mix of toughness and flexibility for the weaving of root bridges, and a number of them can be found in the area. The most spectacular is the "Umshiang Double-Decker Root Bridge," which is two of the bridges growing one on top of the other.

(Photo: Arshiya Urveeja Bose/CC BY 2.0)

(Photo: Anselmrogers /CC BY-SA 4.0)

(Photo: Ashwin Kumar/CC BY-SA 2.0)

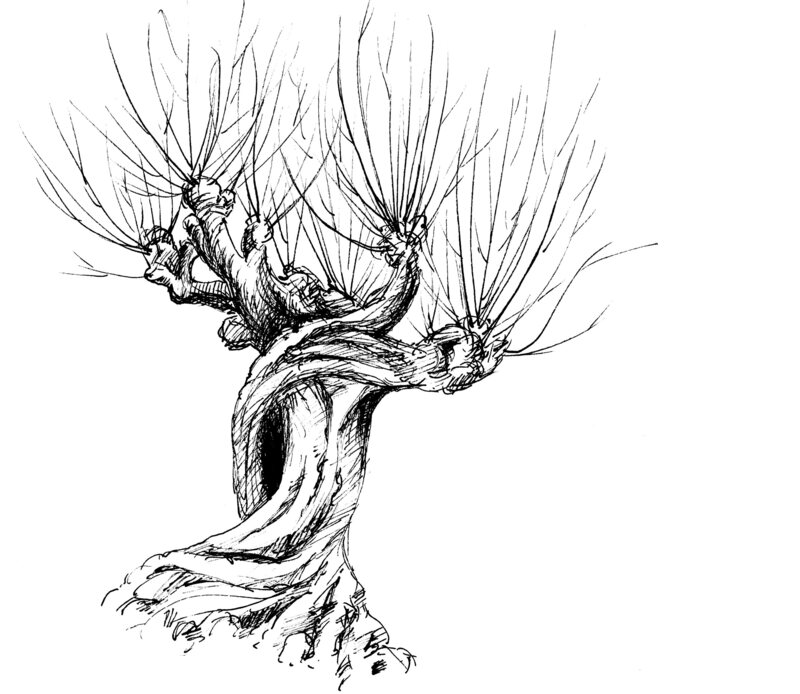

7. Gilroy Gardens

Gilroy, California

(Photo: Martin Lewison/CC BY-SA 2.0)

Some of the pioneering tree shapers of all time never attempted anything as grand as an entire living building or bridge, but created some amazing pieces of living art nonetheless. Horticulturalist Axel Erlandson's "Circus Trees," which he began shaping in the 1920s, are a prime example. By pruning, grafting, and bending branches, Erlandson created some striking trees shaped like baskets and figure eights. Erlandson died in 1964, but his trees are still on show at California's Gilroy Gardens.

(Photo: Jeremy Thompson/CC BY 2.0)

(Photo: Jeremy Thompson/CC BY 2.0)

(Photo: Jeremy Thompson/CC BY 2.0)

8. Reames Arborsmith Studios

Williams, Oregon

(Photo: Richard Reames/CC BY-SA 3.0)

"Arborsculptor" Richard Reames is a visionary artist who has turned his home into a gallery for his amazing living sculptures. They are made from trees that have been grafted, twisted, and trained into a wide array of shapes, including a peace sign. In addition to abstract designs, Reames grows and shapes pieces of living furniture.

(Photo: Richard Reames/Public Domain)