North Korea (photograph by Darmon Richter)

North Korea (photograph by Darmon Richter)

North Korea might not be everybody's first choice of holiday destination. In fact, many remain oblivious to the fact tourism to North Korea is even a thing. In fairness, it’s easy to see how anyone who follows the news might find a leisurely holiday in the DPRK (or “Democratic People’s Republic of Korea”) to be irreconcilable with everything they think they know about the place: a totalitarian nightmare of gulags and thought police, poverty and oppression.

This article is to examine the nature of tourism in North Korea, and to speculate just how much any of us can ever truly know about this secretive “Hermit Kingdom.”

The Quest for Authenticity

The search for authentic insight into other cultures has become a cliché; it is the Holy Grail of the backpacker, the travel blogger’s muse, the driving force behind many an off-the-beaten-path adventure. This trope of travelers searching for an unspoiled slice of foreign heaven formed the premise of Alex Garland’s 1996 novel The Beach. The blockbuster film which followed generated enough traffic to virtually destroy the chances of stumbling across such paradise in Thailand. The remote Thai island known as Koh Phi Phi, where Garland set his story, is now a chaos of hotels, bars, souvenir shops, and strip clubs. This beach paradise has been fully commercialized.

Statues of the nation's leaders on Mansu Hill, Pyongyang (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A man waits for a bus on a street in Pyongyang (photograph by Darmon Richter)

So what about North Korea? As far as original travel goes, it doesn’t get much more off-the-grid than the DPRK — a country that we Westerners know so very little about and where email, phones, and messaging are as good as forbidden. The conservative nature of tourism to North Korea however, makes the prospect of authentic interaction all the more elusive.

Getting into North Korea is easy. Most passports — US included — require only the approval of a basic tourist visa, a process which generally takes less than a month. Discovering authentic culture however, embracing the real North Korea, may prove somewhat more difficult.

The Illusion of Pyongyang

The truth is, the North Korean government doesn’t want you to see their reality. Western tourists are allotted trained guides, whose job it is to show you all the sights approved by the nation’s leadership. In fairness, it’s as thorough and culture-packed a tour as you’re ever likely to experience, a whistle-stop ride around the DPRK’s landmarks and museums, monuments, palaces, memorials, and mausoleums. They’ll treat you to fine examples of traditional Korean cuisine, while every site you visit will (sometimes literally) roll out the red carpet for your approach. You’ll get to skip the queue at Mangyongdae Funfair. Children will sing and dance for your entertainment.

Kim Il-sung Square, Pyongyang (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A young girl performs for tourists at a school in Rason (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Most visitors opt for a tour of Pyongyang, the nation's capital, and it is here amidst the homes and schools of the North Korean elite that one gains the most skewed illusion of life in the country. Reason being, Pyongyang is actually quite a lovely city. Your tour guides are trained to talk their way around questions of poverty and starvation, while the vast majority of beggars know better than to show their face before a group of foreigners. Tour coaches even seem to stick to select, approved roads as they travel through the city, sometimes leading visitors in bizarrely complex routes around the capital, in what one can only assume is an effort to minimize contact with the less-affluent districts of Pyongyang.

Pyongyang then, is hardly the “real” North Korea, but there are times when the veil shifts just enough to allow a glimpse beneath.

On my first trip to the DPRK, we visited the “Grand People's Study House” — Pyongyang’s pagoda-style university building, equipped with an impressive array of computer terminals and a library stocked with government-approved publications. (There’s plenty of Jane Austen, but not much from the last 50 years of Western literature.) On the way out, passing a statue of Eternal President Kim Il-sung seated in a marble-lined foyer, the lights suddenly went out. There were shouts, hisses in the dark, and then the power flicked back on. I was left with the distinct impression that such luxuries as electricity were reserved for those occasions when there was someone to impress.

The Grand People's Study House, Pyongyang (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A statue of Kim Il-sung in the foyer of the Study House (photograph by Darmon Richter)

One of the many classrooms inside the Grand People's Study House (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Outside, we passed an ornate fountain, and our guide told us that we’d missed the display by a matter of hours. But the water feature was inactive, the pool it stood in empty and choked with dry dust.

Alternative Travel in North Korea

This illusion of prosperity is more difficult to maintain as soon as one ventures outside of Pyongyang. Other tourist attractions in North Korea include the ancient Korean capital of Kaesong in the south, and the infamous tour of the DMZ (“Demilitarized Zone”): the heavily-secured border that divides the Korean peninsula some 180km south of Pyongyang. Visiting these sites necessitates a certain degree of travel, and it is here that the illusion begins to shatter.

Tour guides typically issue blanket rules of “no photography on the bus” as you speed along straight, empty roads, between fields where laborers herd goats or harvest crops with their bare hands. Much like neighboring China, North Korea features an abundance of bicycles; unlike China there are very few cars to be seen, even when traveling main highways that run the full length of the country.

The main street in the southern city of Kaesong (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Bicycles and political posters in Kaesong (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Within minutes on the bus, the guide has been ignored. Cameras come out, and up and down the length of the vehicle tourists are snapping illicit photos out the window. Some get caught and receive a stern — yet always incredibly polite — telling off. Most, however, get away with it.

Even here though, in the rural provinces, there are times when it feels an effort is made to maintain some form of illusion. I visited a waterfall one time near Kaesong, where our group ran into a horde of uniformed school children on a day trip. Nearby, several families sang karaoke and danced beside a barbecue in the woods. It was an idyllic scene, until I remembered that it was the school holidays. The families were still there when we left. As we boarded our coach, the only other transportation in sight was another bus featuring government-issue number plates. It was hard not to conclude that we had been surrounded by actors all afternoon.

Separating Truth From Fiction

It’s impossible to hide a country, to make an entire people disappear. There are stories that the North Korean government fills its fields with smiling workers, a nation-wide deception for the benefit of visitors. The truth though, is that observant tourists will always see between the gaps. You’re hardly going to witness one of the political executions that many defectors insist are presented as public events, but try as your guides might to restrict your interaction to trained tourism agents and upmarket city districts, you will see poverty.

A poorer suburb of Rason, a city in the northeast of the DPRK (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A rural scene from just outside Rason (photograph by Darmon Richter)

I even saw a beggar once on a visit to Rason, a city in the northeast of the country. There were pickpockets, too, children who tugged at our jackets as they brushed by in a crowded market. Such experiences are rare for tourists, and all but completely controlled in the capital.

Perhaps the strangest part of it all is that these imperfections North Korea tries to hide are universal flaws. Hunger, crime, poverty, violence, are all intrinsic to virtually every city on the face of the earth. The desperation of the North Korean regime to pretend such things don’t affect them would seem to be politically inspired; perhaps they consider these faults representative of more than just a race, a nation, but deeper still, a critique of their social ideology. To acknowledge such problems, to allow others to acknowledge them, would be to undermine the intelligence and foresight of the DPRK’s founder, President Kim Il-sung, by whose political philosophy of “Juche Thought” the nation is still governed.

Politics aside, North Korea is a very real place. It is largely unexplored by outsiders, untouched by commercialization, and in some ways, in certain places, this mountainous landscape with its forests and beaches does present a kind of unspoiled paradise. But for the time being at least, the only way visitors are likely to witness this North Korea is through glass.

Locals pay respect to Kim Il-sung at a monument in Pyongyang (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Two women deep in conversation in a Rason suburb (photograph by Darmon Richter)

A work party await their transport back to the city (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Pedestrians stop to watch a political broadcast in a park in Rason (photograph by Darmon Richter)

Yap stone in Micronesia (photograph by

Yap stone in Micronesia (photograph by

Spade money with hole for the handle (photograph by

Spade money with hole for the handle (photograph by  Knife money from the Capital Museum, Beijing (photograph by

Knife money from the Capital Museum, Beijing (photograph by  Stacks of hyperinflationary Weimar Germany Marks (via

Stacks of hyperinflationary Weimar Germany Marks (via

The Antikythera mechanism (photograph by

The Antikythera mechanism (photograph by

Greek technical diver Alexandros Sotiriou discovers an intact "lagynos" ceramic table jug and a bronze rigging ring on the Antikythera Shipwreck. (photograph by Brett Seymour, courtesy Return to Antikythera 2014)

Greek technical diver Alexandros Sotiriou discovers an intact "lagynos" ceramic table jug and a bronze rigging ring on the Antikythera Shipwreck. (photograph by Brett Seymour, courtesy Return to Antikythera 2014) Statue recovered in 1901, now on display in the Athens National Museum (photograph by

Statue recovered in 1901, now on display in the Athens National Museum (photograph by

National Park Neusiedler See-Seewinkel in Austria, part of the European Green Belt (photograph by

National Park Neusiedler See-Seewinkel in Austria, part of the European Green Belt (photograph by  The European Green Belt (image by

The European Green Belt (image by  Podyjí National Park in the Czech Republic (photograph by

Podyjí National Park in the Czech Republic (photograph by  Construction of the Berlin Wall, a prominent stretch of the Iron Curtain (

Construction of the Berlin Wall, a prominent stretch of the Iron Curtain ( Eurasian lynx were reintroduced into high-quality habitat in Germany's Harz Mountains in an early European Green Belt project (photograph by

Eurasian lynx were reintroduced into high-quality habitat in Germany's Harz Mountains in an early European Green Belt project (photograph by  A white-tailed eagle, one of the apex predators calling the European Green Belt home (photograph by

A white-tailed eagle, one of the apex predators calling the European Green Belt home (photograph by  An abandoned DDR watch tower in Germany (photograph by

An abandoned DDR watch tower in Germany (photograph by  An overgrown border patrol path from the DDR (photograph by

An overgrown border patrol path from the DDR (photograph by

Emblem from Daniel Cramer's 1624 "Emblemata Sacra" (all images via

Emblem from Daniel Cramer's 1624 "Emblemata Sacra" (all images via

Luis Ricardo Falero, "The Witches' Sabbath" (1880), oil on canvas (via

Luis Ricardo Falero, "The Witches' Sabbath" (1880), oil on canvas (via  Francisco Goya, "Witches' Sabbath (The Great He-Goat)" (1821-1823), oil on canvas

Francisco Goya, "Witches' Sabbath (The Great He-Goat)" (1821-1823), oil on canvas  Albert Joseph Pénot, "Départ pour le Sabbat" (1910) (via

Albert Joseph Pénot, "Départ pour le Sabbat" (1910) (via  Luis Ricardo Falero, "Witches Going to Their Sabbath (or The Departure of the Witches)" (1878), oil on canvas (via

Luis Ricardo Falero, "Witches Going to Their Sabbath (or The Departure of the Witches)" (1878), oil on canvas (via

Photo taken from a roll of film found at the camp of the Dyatlov Pass incident (via

Photo taken from a roll of film found at the camp of the Dyatlov Pass incident (via  Skiers setting up camp at about 5. p.m. on Feb. 2, 1959. Photo taken from a roll of film found at the camp of the Dyatlov Pass incident (via

Skiers setting up camp at about 5. p.m. on Feb. 2, 1959. Photo taken from a roll of film found at the camp of the Dyatlov Pass incident (via  A view of the tent as the rescuers found it on Feb. 26, 1959 (via

A view of the tent as the rescuers found it on Feb. 26, 1959 (via  Monument to the dead skiers (photograph by

Monument to the dead skiers (photograph by  Detail of the monument with photographs of the skiers (photograph by

Detail of the monument with photographs of the skiers (photograph by

The four groups of cities with typical street patterns for each group (

The four groups of cities with typical street patterns for each group ( NYC and its different boroughs' fingerprints (

NYC and its different boroughs' fingerprints (

By Brian Choo, Finders University

By Brian Choo, Finders University

Ebola facility in Sierra Leone, August 2, 2014 (©

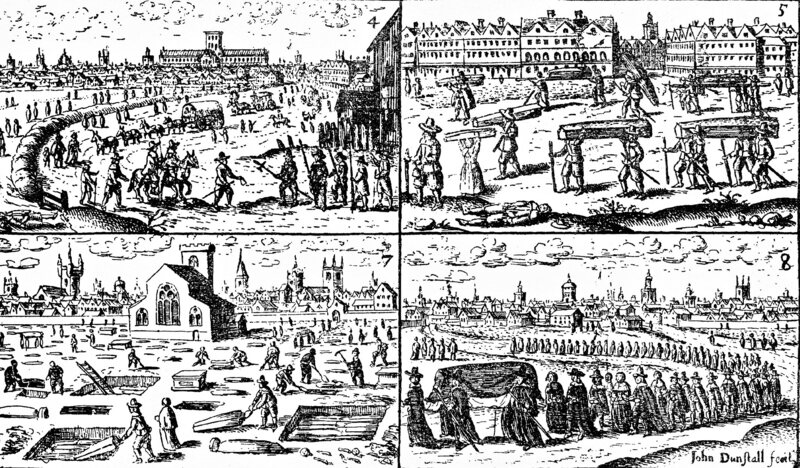

Ebola facility in Sierra Leone, August 2, 2014 (© Scenes of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (via

Scenes of the Great Plague of London in 1665 (via  Quarantined children of cholera victim (early 20th century) (via

Quarantined children of cholera victim (early 20th century) (via

photograph by

photograph by  Poster in Vietnam warning against H5N1 (photograph by

Poster in Vietnam warning against H5N1 (photograph by  A compulsory mask for a post-WWI flu epidemic in Australia (via

A compulsory mask for a post-WWI flu epidemic in Australia (via

Photo of the week: "Cata Sopros," an interactive sound installation by

Photo of the week: "Cata Sopros," an interactive sound installation by  "Knut Ekwall Fisherman and The Siren" by Knut Ekvall (

"Knut Ekwall Fisherman and The Siren" by Knut Ekvall (

Trunyan Cemetery (photograph by

Trunyan Cemetery (photograph by  Some of the bacteria residents at Micropia (via

Some of the bacteria residents at Micropia (via  Radio City's secret apartment (photograph by

Radio City's secret apartment (photograph by  Colonia Fara (photograph by

Colonia Fara (photograph by  Grave of Joseph Palmer (photograph by

Grave of Joseph Palmer (photograph by

"Knut Ekwall Fisherman and The Siren" by Knut Ekvall (

"Knut Ekwall Fisherman and The Siren" by Knut Ekvall ( "Trepanation - feldbuch-der wundartzney" by Hans von Gersdorff (

"Trepanation - feldbuch-der wundartzney" by Hans von Gersdorff (

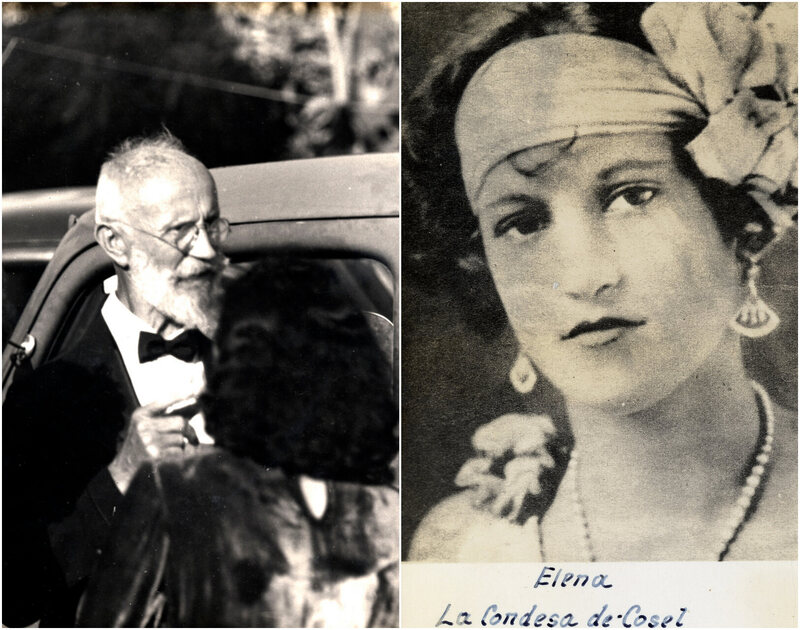

Carl Tanzler (via

Carl Tanzler (via  Elena's Tomb (via

Elena's Tomb (via  Elena's Airship (via

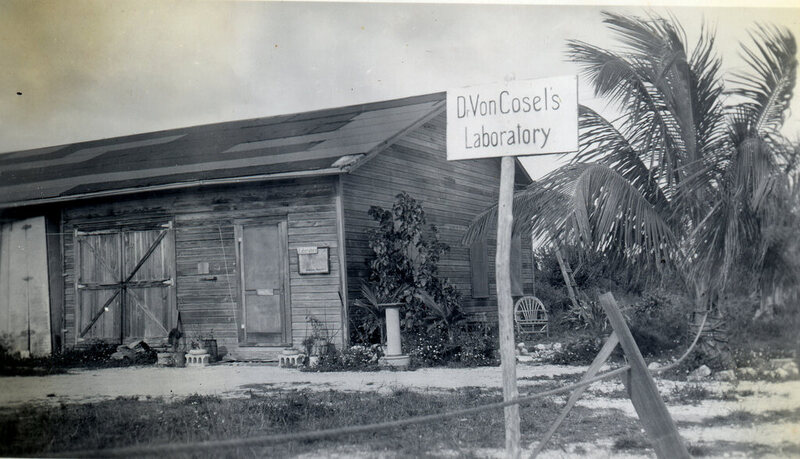

Elena's Airship (via  Carl's home and laboratory(via

Carl's home and laboratory(via

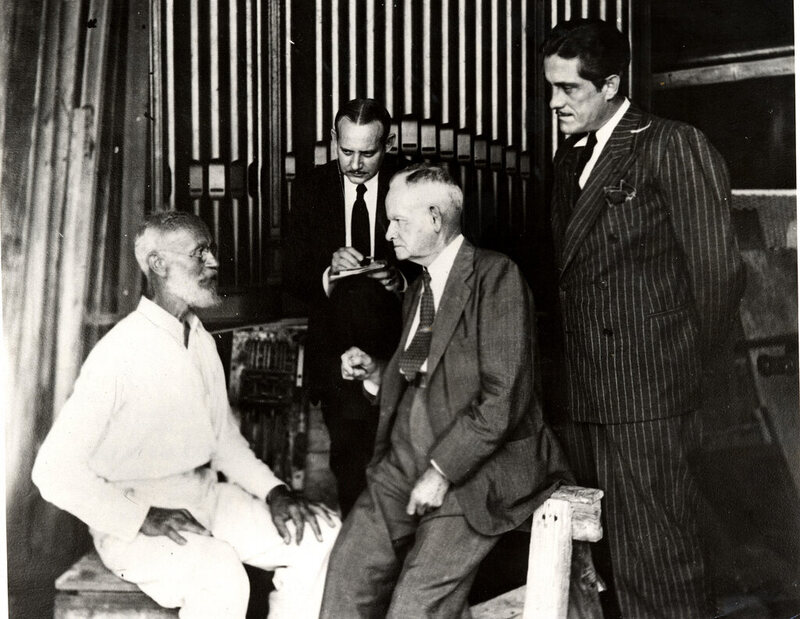

Tanzler during his trial (via

Tanzler during his trial (via

Cemetery at Austin State School Farm Colony (photograph by

Cemetery at Austin State School Farm Colony (photograph by  Shrine on the way to the cemetery (photograph by

Shrine on the way to the cemetery (photograph by  Austin State School Farm Colony (photograph by

Austin State School Farm Colony (photograph by  Danvers State Hospital Cemetery (photograph by

Danvers State Hospital Cemetery (photograph by  Danvers State Hospital Cemetery (photograph by

Danvers State Hospital Cemetery (photograph by  Danvers State Hospital reborn as condos (photograph by

Danvers State Hospital reborn as condos (photograph by  Athens Lunatic Asylum cemetery (photograph by

Athens Lunatic Asylum cemetery (photograph by  Epitaph on a patient tombstone (photograph by

Epitaph on a patient tombstone (photograph by  Part of the Athens Lunatic Asylum turned into the Kennedy Art Museum at Ohio University (photograph by

Part of the Athens Lunatic Asylum turned into the Kennedy Art Museum at Ohio University (photograph by  Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital's cemetery (photograph by

Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital's cemetery (photograph by  Inside Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital before its demolition (photograph by

Inside Marlboro Psychiatric Hospital before its demolition (photograph by  Letchworth Village Cemetery (photograph by

Letchworth Village Cemetery (photograph by  Letchworth Village Cemetery (photograph by

Letchworth Village Cemetery (photograph by  Letchworth Village in 2011 (photograph by

Letchworth Village in 2011 (photograph by  Letchworth Village Cemetery grave marker (photograph by

Letchworth Village Cemetery grave marker (photograph by  Forest Haven cemetery memorial (photograph by

Forest Haven cemetery memorial (photograph by  Abandoned Forest Haven (photograph by

Abandoned Forest Haven (photograph by  Abandoned Forest Haven (photograph by

Abandoned Forest Haven (photograph by

Greek Fire in action; its secret is now lost (via

Greek Fire in action; its secret is now lost (via

Antikythera Mechanism at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece (photograph by

Antikythera Mechanism at the National Archaeological Museum, Athens, Greece (photograph by

Houdini's scrapbook (via

Houdini's scrapbook (via  Houdini's grave in Queens, New York (photograph by Allison Meier/Atlas Obscura)

Houdini's grave in Queens, New York (photograph by Allison Meier/Atlas Obscura)

Satellite calibration targets in the Gobi Desert (Google Maps image via

Satellite calibration targets in the Gobi Desert (Google Maps image via

Tri-bar satellite calibration targets in Fort Huachuca, Arizona (image via

Tri-bar satellite calibration targets in Fort Huachuca, Arizona (image via Salar de Uyuni (image via

Salar de Uyuni (image via  Railroad Valley, Nevada (image via

Railroad Valley, Nevada (image via  World's Largest Compass Rose (image via

World's Largest Compass Rose (image via

courtesy Skulls Unlimited

courtesy Skulls Unlimited Dermestid beetles in action (courtesy Skulls Unlimited)

Dermestid beetles in action (courtesy Skulls Unlimited) Cleanings bones with beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Cleanings bones with beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz) courtesy Skulls Unlimited

courtesy Skulls Unlimited Bones & beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Bones & beetles (photograph by Matt Blitz) Bird skeletons (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Bird skeletons (photograph by Matt Blitz)

Hashima Island (photograph by

Hashima Island (photograph by

Hashima Island in 2014 (photograph by

Hashima Island in 2014 (photograph by  Hashima Island in 2010 (photograph by

Hashima Island in 2010 (photograph by  Poveglia Island (photograph by

Poveglia Island (photograph by  Poveglia Island in 2010 (photograph by

Poveglia Island in 2010 (photograph by  Poveglia Island in 2010 (photograph by

Poveglia Island in 2010 (photograph by  Holland Island in 2010 (photograph by

Holland Island in 2010 (photograph by  Collapse of the house in 2010 (photograph by

Collapse of the house in 2010 (photograph by  Herschel Island (photograph by

Herschel Island (photograph by  Herschel Island in 2010 (photograph by

Herschel Island in 2010 (photograph by  Herschel Island in 2010 (photograph by

Herschel Island in 2010 (photograph by  Ross Island (photograph by

Ross Island (photograph by  Ross Island in 2009 (photograph by

Ross Island in 2009 (photograph by  Ross Island in 2000 (photograph by

Ross Island in 2000 (photograph by  Hirta Island (photograph by

Hirta Island (photograph by  Sheep at Hirta (photograph by

Sheep at Hirta (photograph by

Hirta Island in 2010 (photograph by

Hirta Island in 2010 (photograph by  Spinalonga (photograph by

Spinalonga (photograph by  Spinalonga in 2011 (photograph by

Spinalonga in 2011 (photograph by  Spinalonga in 2009 (photograph by

Spinalonga in 2009 (photograph by  North Brother Island (photograph by

North Brother Island (photograph by  North Brother Island in 2013 (photograph by

North Brother Island in 2013 (photograph by  North Brother Island in 2014 (photograph by

North Brother Island in 2014 (photograph by

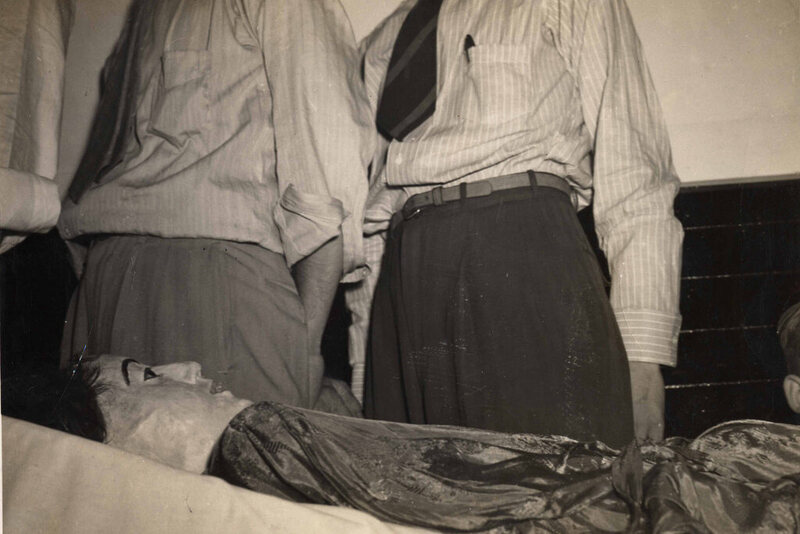

Gargoyle under Budapest (via

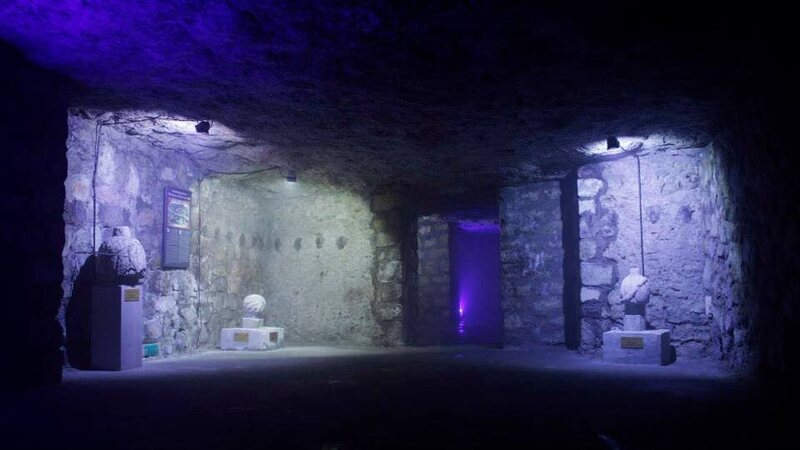

Gargoyle under Budapest (via  Inside the labyrinth (photograph by

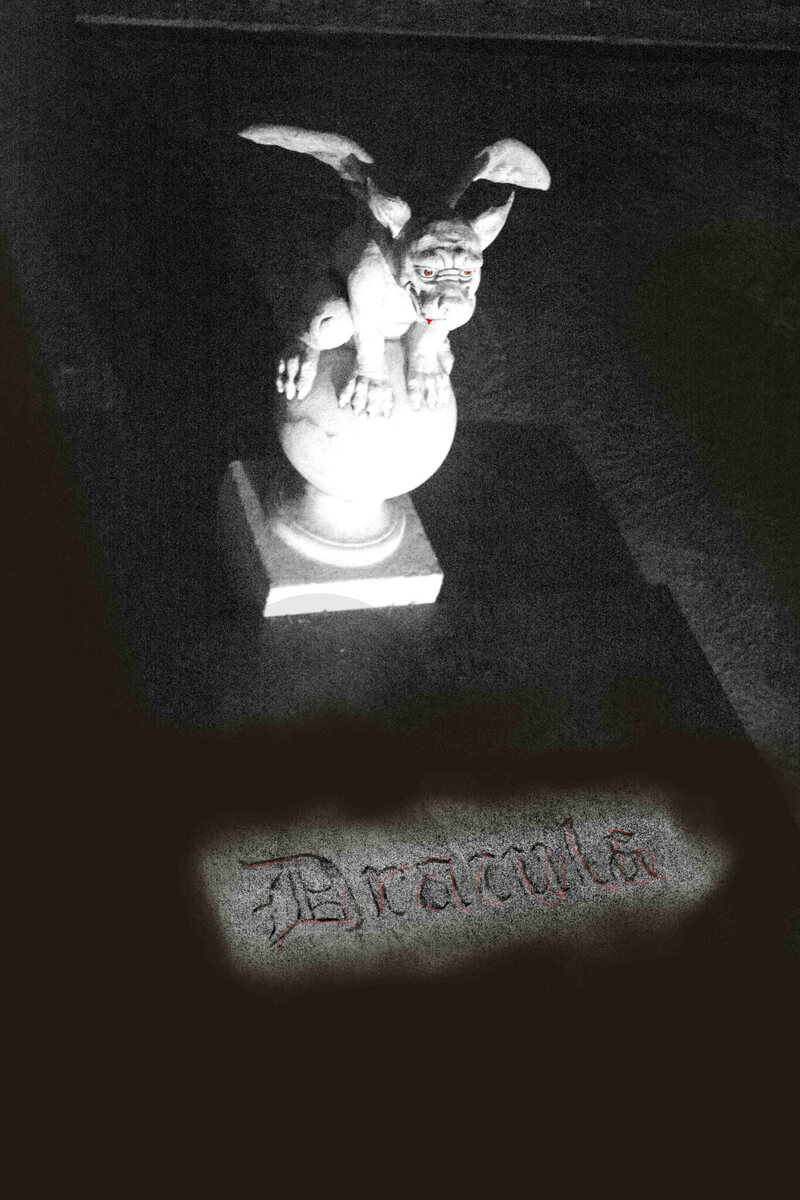

Inside the labyrinth (photograph by  Dracula gargoyle in the labyrinth (photograph by

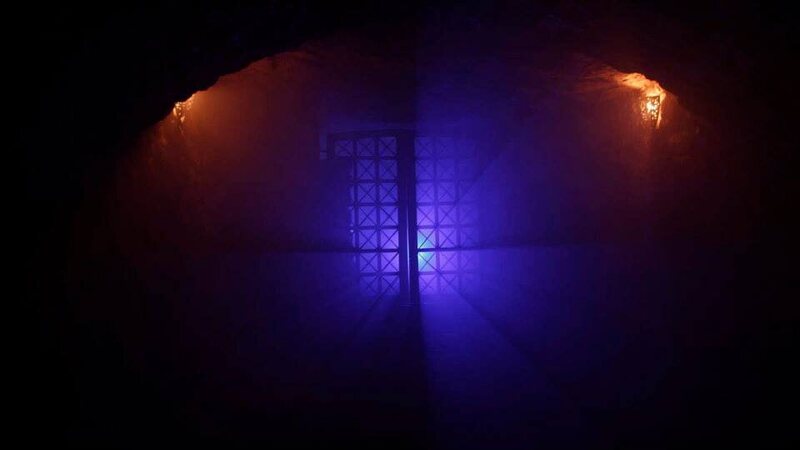

Dracula gargoyle in the labyrinth (photograph by  Illumination in the labyrinth (via

Illumination in the labyrinth (via  via

via  via

via  via

via  photograph by the author

photograph by the author