A Nike missile on a launcher. It could reach speeds of 1,700 mph in just 4 seconds while carrying a 40KT warhead. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

On a narrow strip of heavily wooded land, ringed with beaches and jutting out six miles from the coast of Northern New Jersey into the Atlantic Ocean, sits a remarkable secret.

At first, it looks like the top deck of an aircraft carrier. An old iron barbed wire fence surrounds the giant slab of concrete, which is hidden in layers of undergrowth. Faded yellow-painted markings, what looks like long rusted bay doors, are embedded into the floor. Old loudspeakers and disused arc lamps mark the perimeter.

This was one of the most highly classified, top secret locations in the United States, a Nike missile base called Fort Hancock. If you were caught anywhere near it in the last 50 or so years, the heavily armed patrols had orders to release their vicious attack dogs and shoot to kill on sight. Now in ruins, these forgotten remnants were New York’s last line of defense against Soviet nuclear attack.

The remains of the Nike launch site at Fort Hancock. Missiles would emerge from underground to neutralize the Soviet threat. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Named for the Greek winged goddess of victory, and developed by Bell Telephone Laboratories, the Nike missile was a surface-to-air missile, guided by radar and a tracking computer. The program started in 1945, spurred by two cataclysmic events: the first successful atomic bomb test by the Soviet Union and their development of a long range bomber capable of 10,000-mile distances. The threat of Soviet aircraft carrying atomic weapons suddenly became very real. The Nike missiles were a solution to prevent another Pearl Harbor from happening.

The radar system would constantly monitor the skies for Soviet planes, while another radar would lock onto any plane invading U.S. airspace, and track it. The radar would co-ordinate with the missile’s computer to zero in on the plane and destroy it.

Nike Hercules missiles at Fort Hancock in the firing position. (Photo: NPS/GATEWAY NRA Museum Collection)

Nike Hercules missiles at Fort Hancock in the firing position. (Photo: NPS/GATEWAY NRA Museum Collection)

A drawing showing data flow of radar at control area from 'Procedures and Drills for the NIKE Ajax System,' 1956 (Photo: Library of Congress)

A drawing showing data flow of radar at control area from 'Procedures and Drills for the NIKE Ajax System,' 1956 (Photo: Library of Congress)

Western Electric began manufacturing the system with the missiles engineered by Douglas Aircraft. The first version called the Nike Ajax was ready to be deployed by 1954. It was superseded in 1958 with the even more powerful Nike Hercules. They were situated in hidden batteries surrounding America’s most important strategic cities, in what the U.S. Army Ordnance brochure called“Rings of Supersonic Steel”. By 1963 there were over 200 Nike sites defending the U.S. against the threat of Soviet annihilation. Los Angeles, home to most of the U.S. aerospace industry, was a principal target, as was Chicago and Indiana, which had the bulk of U.S. steel. According to a well-sourced Wikipedia list, New York had 19 missile sites to protect it should the unthinkable happen.

The Nike missile family in the 1960s. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Launch sites were divided into three main areas, which had to be at least 1,000 yards apart. The radar system, a camp of barracks and mess halls for the 100 men who manned the base, and the missile silos themselves. Often the missile sites were built on existing military installations, which meant that in New York City, many 19th century forts built to protect the city with more conventional heavy artillery were repurposed into Nike sites. (Fort Totten and Fort Tilden, for example.) Due to their brief, the sites had to surround the city they were designed to protect, so many Nikes were secreted away in the backyards of Long Island, Westchester, and the potter’s field of Hart Island. The sites were hidden, with good reason, since the Hercules missile was armed with a "Big Red" nuclear warhead with a yield of about 30 to 40 kilotons of TNT. (The bomb that obliterated Hiroshima was 13 kilotons.) Military security surrounding the sites had zero tolerance for intruders.

The remains of the Nike radar installation at Fort Hancock that would track enemy craft and guide the missile to it. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Sandy Hook in New Jersey proved to be an ideal site. Close enough to New York, but remote enough, it had long provided the perfect strategic position for guarding entry into New York harbor due to the deep channel that ran alongside it. Home to America’s oldest lighthouse, the slender spit of land had been fought over since the days of the War of Independence.

The original Fort Hancock was improved upon during the Civil War, and in the 1890s vast concrete gun batteries and mortar pits were built to protect Manhattan. At one point over 7,000 soldiers lived here in an army town that included rows of grand yellow brick homes, officer’s quarters, a theatre and ball fields. The full-scale camp was largely vacated after World War II and given over to a Nike launch site given the code name NY-56.

A Nine Gun battery firing at Fort Hancock in 1941. (Photo: NPS/GATEWAY NRA Museum Collection)

One of the original houses from when Fort Hancock was first built. At one point over 7,000 soldiers lived in this remote town. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The abandoned 19th century battery emplacements, designed to protect Manhattan. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

This launch site borders one of the beaches at the far end of Sandy Hook. The nuclear missiles would have been housed underground in silos about the size of a school gymnasium, from where they would emerge should the threat of a Soviet atomic assault on Manhattan appear on the horizon. As the Army brochure put it:

“The silent sentinels of Nike stand ready for that day, a day we all hope many never come. We must be ready to protect ourselves with the newest weapons science can provide.”

These “newest weapons” came at a cost of billions of dollars as sites sprung up all over America.

About 1,000 yards from the launch site was the radar complex. Today, hidden from view by the forest of the peninsula, the radar guidance systems resemble giant seashells, perched upon rusting squat platforms, looking not unlike they were placed in the forest by the Dharma Initiative.

"Whatever tomorrow may bring.....NIKE will be watching, always ready." Constantly monitoring for Soviet bombers. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

From here the skies were constantly monitored with the official “tactical control” orders in place should the unthinkable happen. A VHF radio message would raise the alarm with the words “BLAZING SKIES : THIS IS NOT A DRILL” broadcast throughout the base, over the now silent loudspeakers surrounding the launch site. “Blazing Skies” was the code words for “aggressor engagement”.

By the 1970s however, the Nikes were rendered obsolete. The advent of the Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile gave way to a new form of terror; a Soviet nuclear attack that didn’t require aircraft. With the ongoing war in Vietnam consuming the bulk of defense expenditure, the Nike program was shelved in 1974’s Strategic Arms Limitation Talks agreement. No Nikes were ever launched in anger over US soil, but the program wasn’t without casualties. In Leonardo, New Jersey, an Ajax missile exploded on May 22nd, 1958, killing six soldiers and four civilians.

What, then, happened then to the Nike missile launch sites? Today there are remnants of around 250 bases around the United States in varying levels of ruin. Those built on existing Army bases were simply decommissioned. Due to their proximity to major cities, some were sold to school districts, or turned into municipal yards. Others found their way into private use and became paintball sites. Some were turned into homes. In Virginia, one base even became a prison.

Waiting for the Blazing Skies call that would alert that an attack was imminent. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

“They are disappearing, dug up, and houses are built on it, and pretty soon there aren’t going to be any of them around,” David Tewksbury, a GIS specialist told Livescience.

Today only a few remain intact. The problem of historic preservation arises due to the relative modernity of the sites. Cold War era structures aren’t as easily protected on the National Register of Historic Places. With no official efforts made to preserve the sites it is left to such volunteer groups as the Cold War Veteran’s Association who are striving to protect and restore the bases in Lorton, VA and LA-43 in California.

With most of the original structures still there, they offer tours of the old radar sites, often given by actual Nike veterans who were based there. Visitors have the opportunity to tour inside the radar sites and “find out what it was like to go on full alert”. The launch site, however, would greatly benefit from more funding and protection. Today it silently rusts away, watching the skies over New York for the attack that never comes.

PS10 glinting in the sunlight. (Photo:

PS10 glinting in the sunlight. (Photo:

(Photo:

(Photo:

Inside the greenhouse of Growing Power. (

Inside the greenhouse of Growing Power. (

Salton Sea (Photo:

Salton Sea (Photo:

McKibbin, Oppenheimer, and a friend hang out in a field. (Photo:

McKibbin, Oppenheimer, and a friend hang out in a field. (Photo:

McKibbin revisits 109 East Palace. (Photo:

McKibbin revisits 109 East Palace. (Photo:

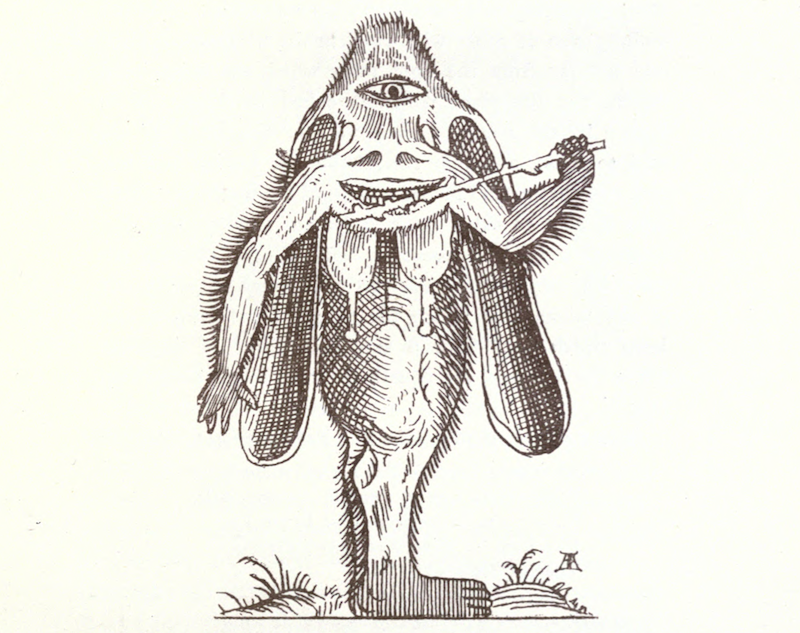

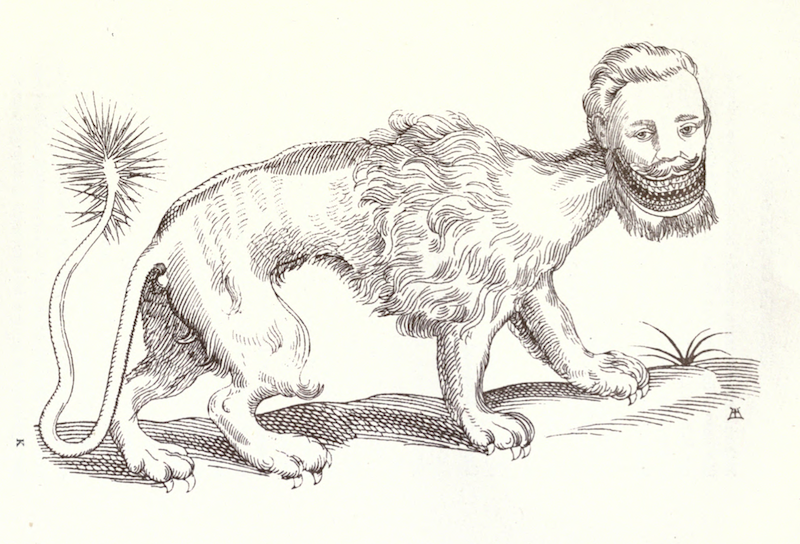

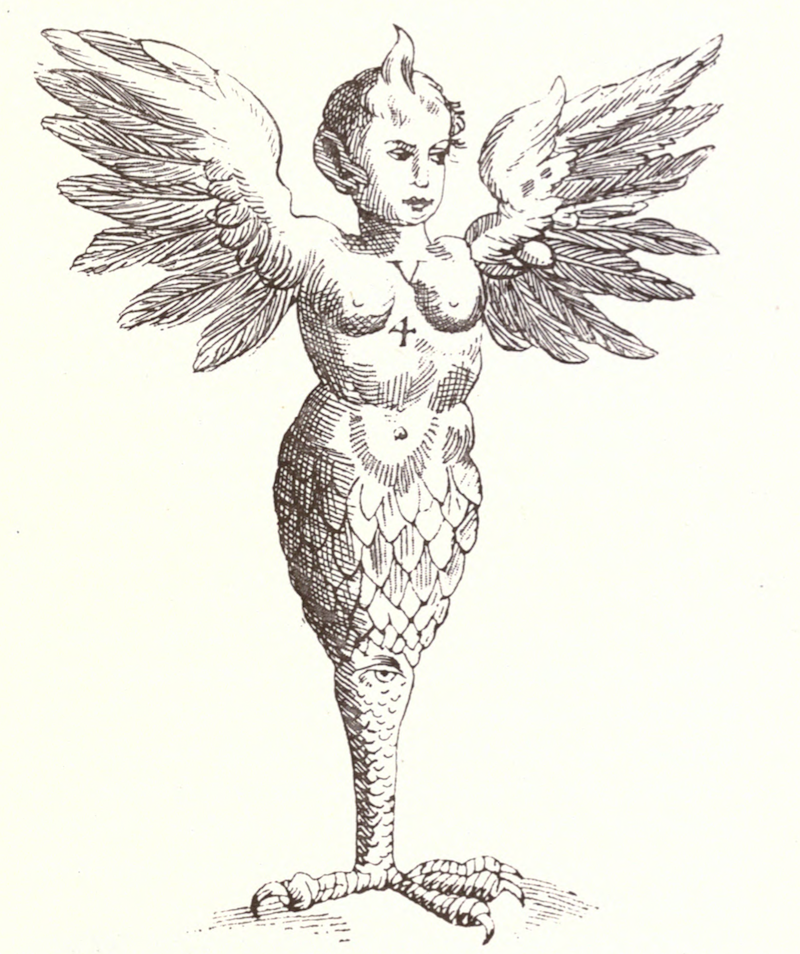

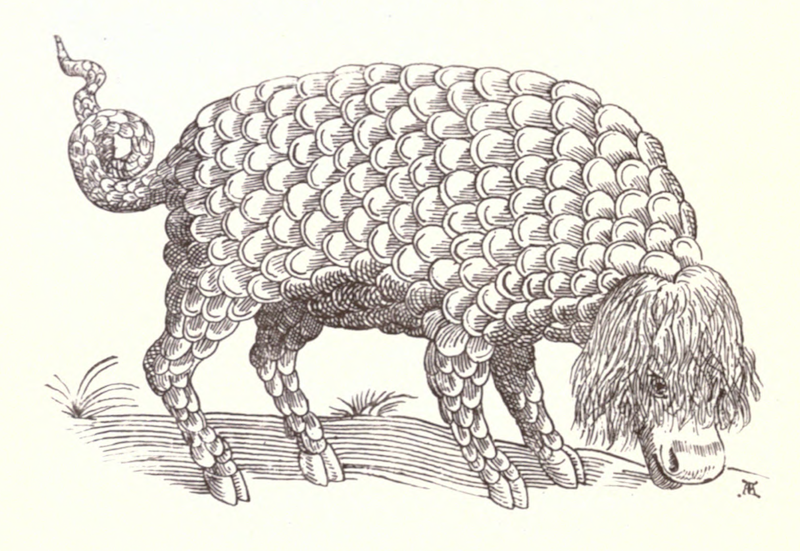

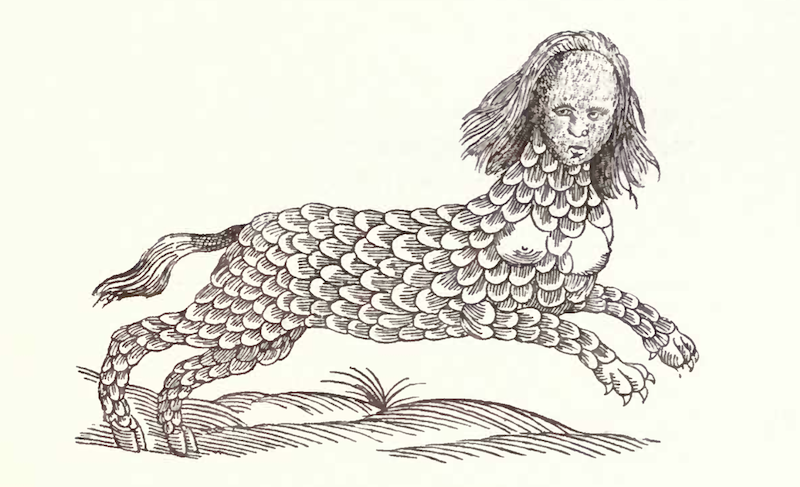

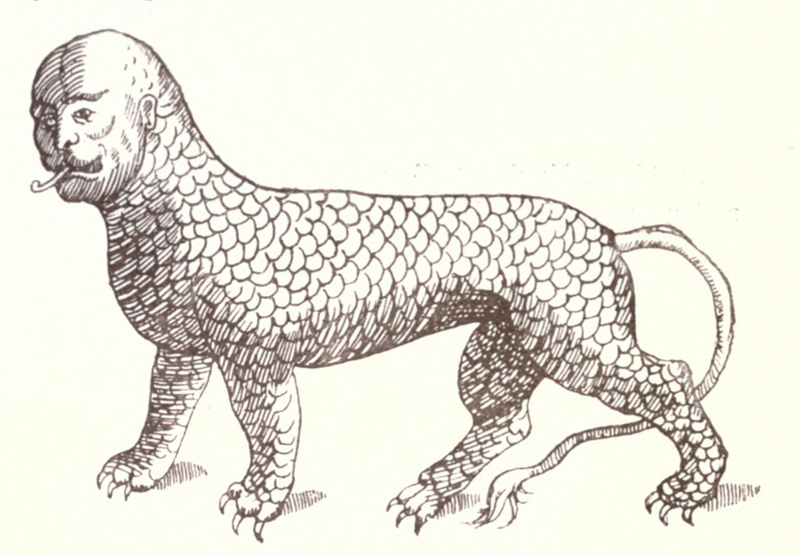

The Manticora, triple-smiling for its portrait. (Image:

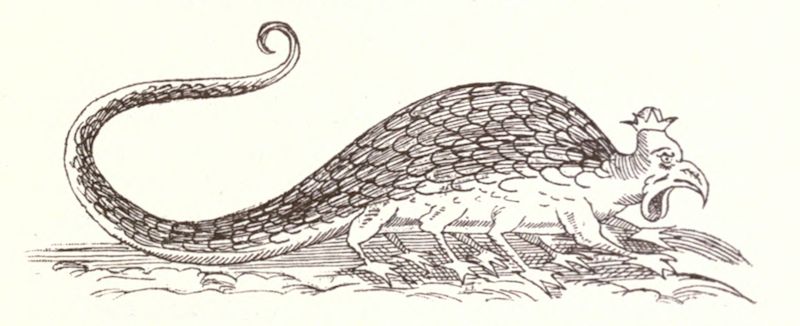

The Manticora, triple-smiling for its portrait. (Image:  The Ravenna, with extra eyes to make up for its lack of limbs. (Image:

The Ravenna, with extra eyes to make up for its lack of limbs. (Image:  The Gorgon re-ups on poysonfull hearbs. (Image:

The Gorgon re-ups on poysonfull hearbs. (Image:  Beware the irresistible gaze of the Lamia. (Image:

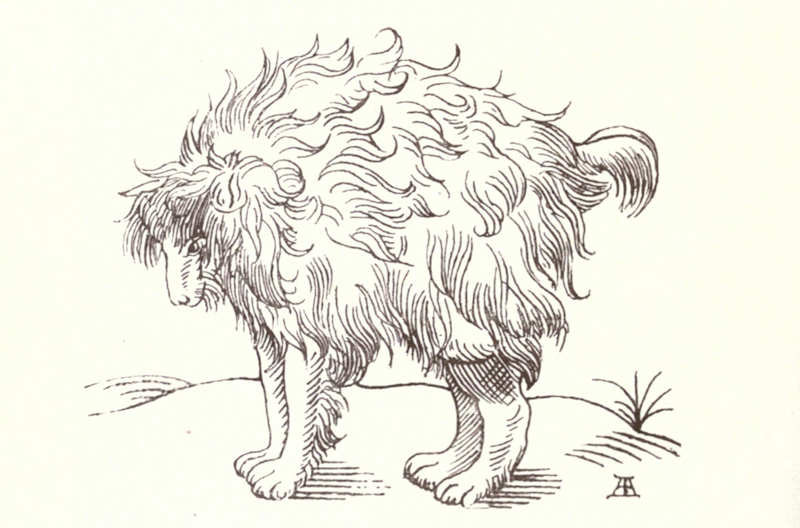

Beware the irresistible gaze of the Lamia. (Image:  The Mimick Dog: Can you even tell it’s him, what with his mimicking skills? (Image:

The Mimick Dog: Can you even tell it’s him, what with his mimicking skills? (Image:

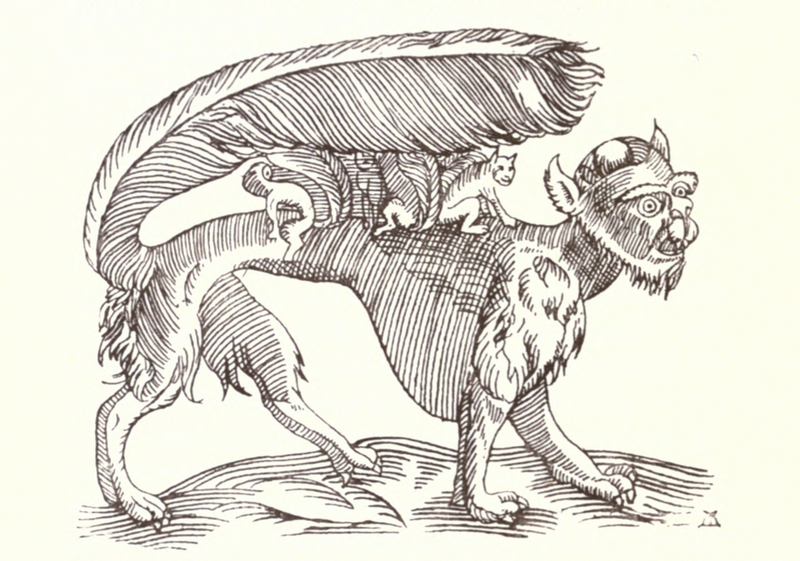

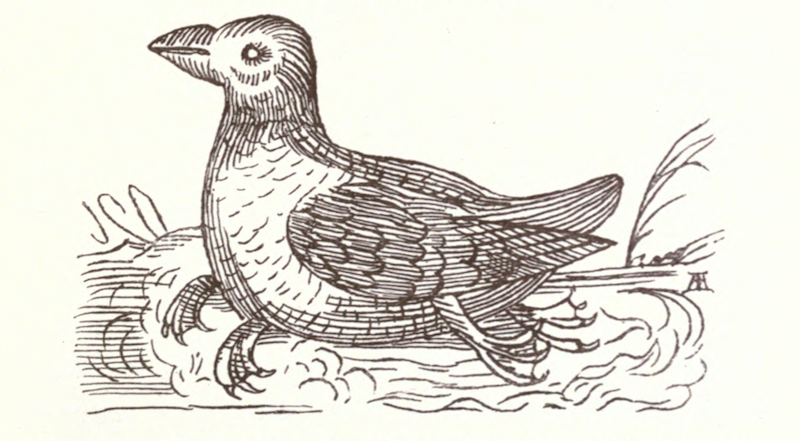

There is some confusion as to whether the Leonine Monster is an aquatic or a land creature. (Image:

There is some confusion as to whether the Leonine Monster is an aquatic or a land creature. (Image:

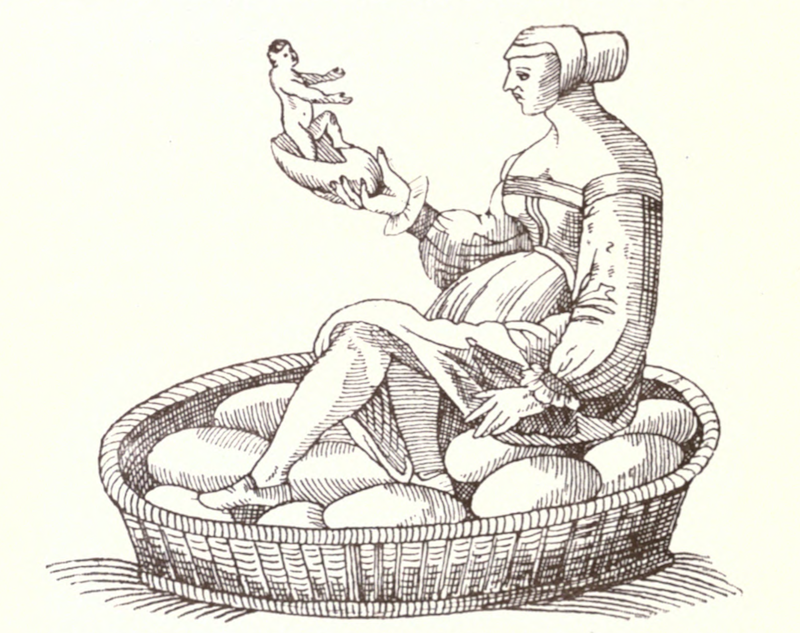

The Moon Woman examines one of her progeny. (Image:

The Moon Woman examines one of her progeny. (Image:

A Map from 1897 showing the Roman Empire with provinces, in 150 AD. (Photo:

A Map from 1897 showing the Roman Empire with provinces, in 150 AD. (Photo:

A Map showing the Appian Way and the shorter Via Appia Traiana. (Photo:

A Map showing the Appian Way and the shorter Via Appia Traiana. (Photo:

Pont Flavien on the Touloubre river in Saint-Chamas, France. (Photo:

Pont Flavien on the Touloubre river in Saint-Chamas, France. (Photo:  The detail of a lion atop the Pont Flavien. (Photo:

The detail of a lion atop the Pont Flavien. (Photo:  The vast Pont du Gare near Nimes, France (above) and below, a closer view of the existing structure. (Photo:

The vast Pont du Gare near Nimes, France (above) and below, a closer view of the existing structure. (Photo:  (Photo:

(Photo:

(Photo:

(Photo:  "Caesar's Dam". (Photo:

"Caesar's Dam". (Photo:

Elisabeth Parlaghy's portrait of her mother, Baroness von Zollerdorff. (Photo:

Elisabeth Parlaghy's portrait of her mother, Baroness von Zollerdorff. (Photo:

Lwoff-Parlaghy's portrait of Nikola Tesla. (Photo:

Lwoff-Parlaghy's portrait of Nikola Tesla. (Photo:

Mayflies emerge from the lake. (Photo:

Mayflies emerge from the lake. (Photo:  Adult mayfly close-up. (Photo:

Adult mayfly close-up. (Photo:  Radar map of mayfly swarm. (Courtesy of

Radar map of mayfly swarm. (Courtesy of

Flat-Earth map by Orlando Ferguson, South Dakota, 1893. (

Flat-Earth map by Orlando Ferguson, South Dakota, 1893. (

Prof. G. William Domhoff in conversation with psychologist Calvin S. Hall at the University of California in 1968. (Photo:

Prof. G. William Domhoff in conversation with psychologist Calvin S. Hall at the University of California in 1968. (Photo:  A Chart of the neural network for dreaming, which is still being refined and researched. (Photo: G. William Domhoff)

A Chart of the neural network for dreaming, which is still being refined and researched. (Photo: G. William Domhoff)

(Photo:

(Photo:  (Photo:

(Photo:  (Photo:

(Photo:  (Photo:

(Photo:  (Photo:

(Photo:  (Photo:

(Photo:

(Photo:

(Photo: