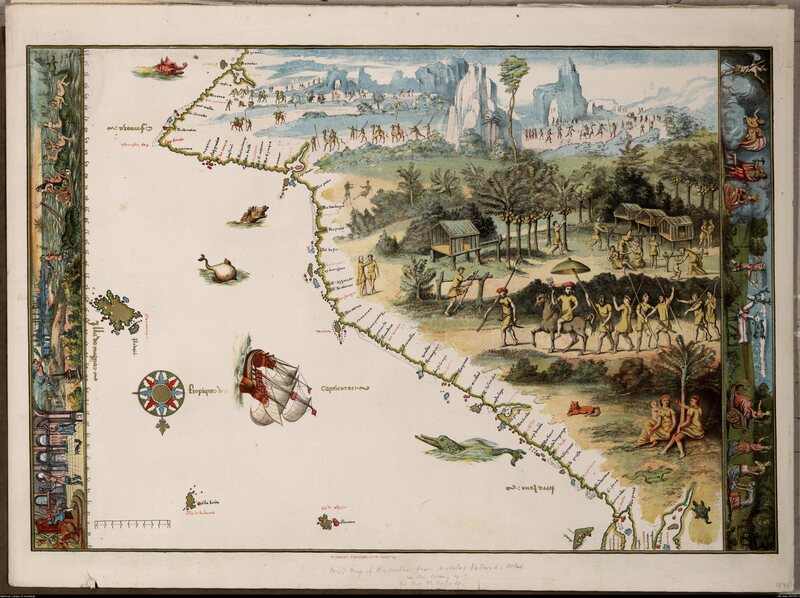

From NAM's website.

"You know the old saying, garbage in, garbage, out." So began the news segment hosted by Bruce Leshan, a weather analyst camped out, like many weather analysts, at the National Weather Service headquarters in Sterling, Virginia, describing the need for good data in the always-tricky field of weather prediction. While the eastern seaboard of the United States is looking out the window or shoveling the driveway at the blizzard coating the region, weather nerds have kept their eye on something else: the weather models.

In particular, the one who got the closest to predicting today's downfalls.

More than two days ago, the 78hr NAM forecast nailed this storm—then kept insisting on huge NYC snow. Coincidence? https://t.co/l99py5zNrl

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 23, 2016

On Saturday morning, as New York City's snow totals began to rise, metereologists and weather watchers took to social media to declare the radar maps a victory for the North American Mesoscale Forecast System or NAM. It seems that NAM has been calling for more snow in NYC than competing systems the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) and the American GFC (made by NOAA) for days—and while there was extraordinary overlap in the different system's predictions, NAM has won big. (This comes after the giant prediction flop that was #snowmageddon last year, when the city shut down the subway system for a storm that barely rated.)

The NAM wins.

— Eric Holthaus (@EricHolthaus) January 23, 2016

This breaks the trend of dismissing NAM's dire predictions for New York.

Weather Weenies: "No one takes the NAM seriously" .."30" in NYC...well it IS better equipped to pick up banding!!" pic.twitter.com/WD787fdLFl

— Keith Carson (@KeithCarson) January 21, 2016NYC...4 different weather models, 4 different snow totals, but 1...WAY different! GFS: 7", RPM: 10", Euro" 11.5"...NAM: 26"! Toss it for now

— Lonnie Quinn (@LonnieQuinnTV) January 21, 2016

The NAM is the Fillmore of weather models. It wants you to believe it's all a conspiracy. But it's probably wrong. pic.twitter.com/C2gq8fPiL5

— Matt Lanza (@mattlanza) January 21, 2016

Even late yesterday, there were NAM doubters.

NAM weather model shows potential for sleet to mix in at peak of storm late tomorrow morning and early afternoon. Still not convinced.

— SWCT/NY Weather Info (@SWCTweather) January 23, 2016

How did NAM do this? To say weather modeling is complicated would understate the case. Meteorologists often like to point out that these projections should be looked at side-by-side, not as an either-or, since the mathematical underpinnings can differ greatly even if some of the data is shared. The European model uses 51 different hypothetical situations, the GFC uses 21. The European model got credit for accurately predicting Hurricane Sandy's path days before any American models came close, but in this case, it seems to be a bit off.

European Model shows the East Coast set to get slammed by strong winter weather; possible records in D.C. pic.twitter.com/KFnLaKJ2Sc

— Good Morning America (@GMA) January 20, 2016

The NAM is a smaller model than the European one, or the GFC. This is Dennis Merseau discussing them when NOAA upgraded its weather modeling resolution last January.

While many weather geeks keep saying that the GFS model now has a similar resolution as the NAM, it's like comparing apples to oranges. The NAM, or the North American Model, is a mesoscale model with a horizontal resolution of 12 kilometers (about 7 miles) that's designed to handle smaller systems across the United States and parts of Canada and Mexico. The GFS is designed to handle large-scale systems like nor'easters, hurricanes, the polar vortex, or the jet stream across the entire world. The 12-km NAM and its much higher resolution counterpart, the 4-km NAM, on the other hand, are great tools to use when you want to forecast convection (thunderstorms).

Of course, "winning" is relative to the harm that this giant weather event is causing. The snow will have to settle before we get a full recap of the weather modeling jeers and cheers. For now, though, if you're sick of watching TV and too cold to go outside, maybe try the soothing livestream of Representative Paul Ryan's office. Pro tip: sound off. The jazz is a bit aggressive.