![article-image]()

But how much money will you give me? (Photo: Gage Skidmore/flickr)

Every job negotiation, no matter how big or small, comes down to one thing: Is it worth my time? But how much, exactly, is our time worth—and how much could someone’s time be worth? And what could possibly make a person’s time worth more than $20 per minute, not to mention $208 per second?

And whose time is worth the most?

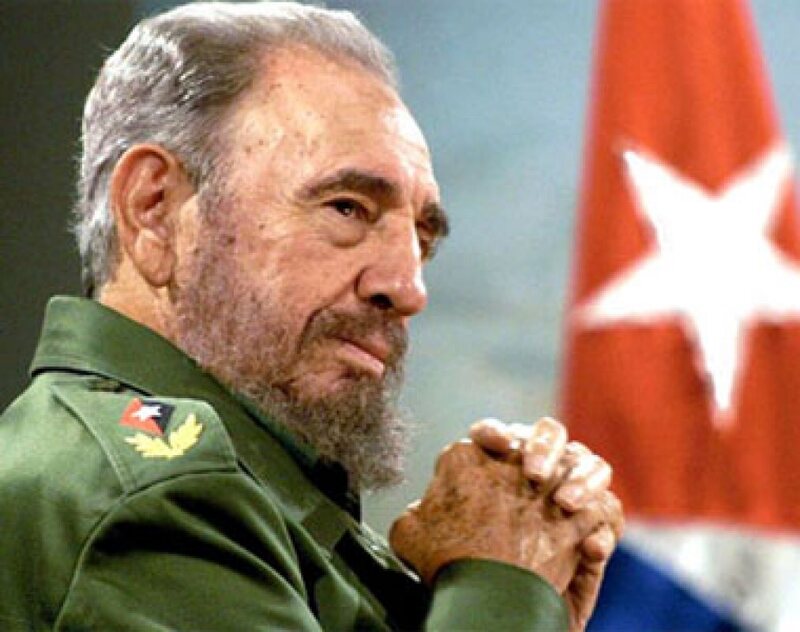

Measurement, of course, is tricky. One of the most efficient ways for someone to maximize the time/money delta is through quick tasks like autographs. Time-wise, we’re looking at, what—two seconds, maybe three? With his autograph worth up to£3,950 ($5,762), you could argue that one second of former Cuban president Fidel Castro’s time is worth $2,881, or 12 times the average annual salary in Cuba. Musician Paul McCartney is second on the Autograph Index; his scribble can go for £2,500 ($3,647), or $1,823 per second of scribbling.

![article-image]()

Mmm, my signature? Might cost you a few bucks. (Photo: Max.dai.yang/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 4.0)

Art is also not a bad racket, if you're Picasso. One of his paintings, "Nude, Green Leaves and Bust", was auctioned for $106.5 million. According to Time, it took him a day to complete, putting that at $73,958 per minute (of a 24-hour day) or $1,232 per second.

But that’s just one way—and a slightly far-fetched one—to measure how much someone’s time might be worth. More often, time is charged by the hour or appearance rather than by the signature or the second. Sometimes, an hour of someone’s time comes with a speech or performance; sometimes, the person just needs to show up.

![article-image]()

Paris Hilton wondering if we're worth her time. Probably not. (Photo: Philip Nelson/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

If you’re looking at time, pure time, time that doesn’t come with anything else—no practice or preparation, no expectations except that you come hang out—then welcome to the world of media moguls and club appearances. Reality star Kim Kardashian has been paid $600,000 to simply sit at a club’s VIP booth and throw a few smiles at party goers, while Paris Hilton, an heiress and socialite, was once paid $2.7 million to hang out and deejay a for few nights in Ibiza for the equivalent of $347,000 an hour, or, since you’re wondering, $5,783.33 a minute—an expensive minute. Other luminaries like Lil Wayne, Britney Spears, and Pamela Anderson have raked in between $250,000 and $350,000 to basically show up at night clubs; if they stick around for four hours, that boils down to about $1,250 a minute.

![article-image]()

Hey, I'm Snooki, and yes I get paid more to speak to students than Toni Morrison. (Photo: Aaron/WikiCommons CC BY-SA 2.0)

In other less lucrative news, Rutgers University once shelled out $32,000 for Jersey Shore reality star Snooki to show up for a one-hour campus Q&A session. That happens to be $2,000 more than the university paid Nobel prize-winning author Toni Morrison to give the commencement address that same year.

But generally, a person’s time is tied to more than their mere physical presence. Usually, someone is expected to deliver something—for example, a private rendition of the happy birthday song. Singer Jennifer Lopez was once paid $1 million to sing "Happy Birthday" and three other songs for the president of Turkmenistan, $2 million for the birthday of Russian bureaucrat Alexander Yelkin, and booked for $2.5 million by the dictatorship of Azerbaijan. (She got some heat for accepting money from some of the world’s most corrupt tycoons, as did singers Lionel Richie, Mariah Carey, Beyonce, and Usher when they performed for Libyan dictator Muammar al-Qaddafi). Regardless of wherever that oil money came from though, (in the case of Turkmenistan’s Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, the China National Petroleum Corp picked up the tab), an hour of Jennifer Lopez was valued at one or two million USD, or $250,000 a minute, though that number should be lowered when one considers she had to schlep all the way to Turkmenistan.

![article-image]()

Smiling because you are paying me thousands per minute. (Photo: Ana Carolina Kley Vita/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

That’s not such a big surprise, especially when we’re talking Gurbanguly Berdimuhamedov, though the numbers might still raise eyebrows when calculated down to the minute. Other performers, such as The Eagles, Rolling Stones, Kanye West, Christina Aguilera, and Taylor Swift can expect $1 million, up to even $6 million for a show. And let’s not forget athletes, whose presence (and product promotion) are pretty pricey. Former NFL running back Tiki Barber’s company at a sports game will cost you $2,000 or $1,000 for a lunch date. If you only have $500 to spare, you could get Rob Gronkowski, New England Patriots tight end, to tweet out your message—and that’s probably one of the cheaper tweets out there.

![article-image]()

One hour, you say? That'll be $1,250—a lot cheaper than Snooki, you know. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Entertainers and athletes aside, lawyers and politicians can also charge a lot for a bit of their time. The Wall Street Journal published a handy list of the hourly rates of the highest charging lawyers, mostly dealing in corporate, tax, and finance, with fees ranging between $1,000 and $1,250 an hour, or $20.83 a minute—or less than $0.35 a second! A steal, really, especially if you think about it as paying not just for that one hour but for all of the time they’ve spent becoming qualified to advise you. It’s also very cheap when you compare it to hiring the Donald (who to clarify, is not a credentialed lawyer).

In 2006 and 2007 one company hired Donald Trump to come give 17 seminars for $1.5 million each. Even if the seminar was a long-winded two hours, that’s still $12,500 per minute, or $208.33 per second. Turns out financial folk like Trump are in high demand, often booked by businesses hoping to boost their bucks and morale. Economist Ben Bernanke, for example, gets up to $400,000 for a speaking engagement.

![article-image]()

Everyone in this family is a prized public speaker. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

But former politicians perhaps hold the most public speaking cache. In 2006, former British Prime Minister Tony Blair took in nearly $616,000 for two half-hour speeches ($10,266.66 a minute), and Bill Clinton can get up to $450,000 for gracing an audience—more than twice the presidential salary ($200,000). In January, Bernie Sanders accused Hillary Clinton of receiving over $600,000 in speaking fees from Goldman Sachs in one year, but compared to Trump, that's nickels and dimes. (Although she did try to charge $275,000 for a lunchtime engagement last February at the University of Missouri at Kansas City; they ended up booking her daughter for $65,000 instead.) Folks like Rudy Giuliani, Alan Greenspan, even Sarah Palin and former first daughter Chelsea Clinton can command more than $75,000 or $100,000 for a speech. A little lower down the ladder, best-selling authors are able to get around $40,000 for a speech (as high as $666 per minute). Not sure how much it costs to book the poet laureate, but probably a lot less.

Of course, oratory requires preparation, and speeches require writing. But, with junior staff to cover those bases, most of those dollars are really going to getting that person in that room. Bragging rights (and selfie opportunities) are also a major boon. “The underlying principle,” Harvey Miller, a New York-based bankruptcy lawyer told the Wall Street Journal, “is if you can get it, get it.”

![article-image]() This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura's Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.

This story appeared as part of Atlas Obscura's Time Week, a week devoted to the perplexing particulars of keeping time throughout history. See more Time Week stories here.